The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, was a secret revolutionary society founded in the Ottoman territories in Europe, that operated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising, or simply the Ilinden Uprising of August–October 1903, was organized revolt against the Ottoman Empire, which was prepared and carried out by the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization, with the support of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee, which included mostly Bulgarian military personnel. The name of the uprising refers to Ilinden, a name for Elijah's day, and to Preobrazhenie which means Feast of the Transfiguration. Some historians describe the rebellion in the Serres revolutionary district as a separate uprising, calling it the Krastovden Uprising, because on September 14 the revolutionaries there also rebelled. The revolt lasted from the beginning of August to the end of October and covered a vast territory from the western Black Sea coast in the east to the shores of Lake Ohrid in the west.

Gotse Delchev, is a town in Gotse Delchev Municipality in Blagoevgrad Province of Bulgaria.

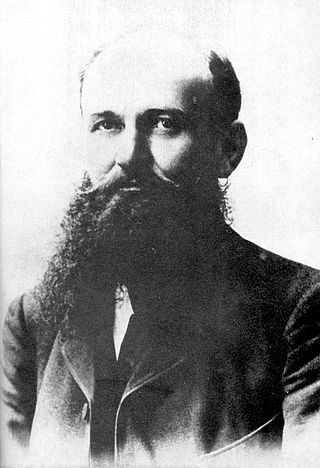

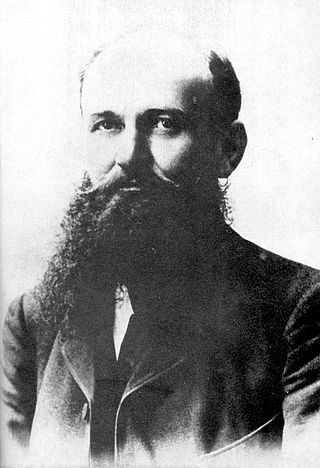

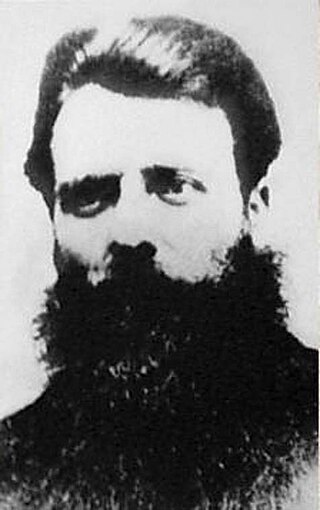

Georgi Nikolov Delchev, known as Gotse Delchev or Goce Delčev, was an important Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary (komitadji), active in the Ottoman-ruled Macedonia and Adrianople regions at the turn of the 20th century. He was the most prominent leader of what is known today as the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), a secret revolutionary society that was active in Ottoman territories in the Balkans at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. Delchev was its representative in Sofia, the capital of the Principality of Bulgaria. As such, he was also a member of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC), participating in the work of its governing body. He was killed in a skirmish with an Ottoman unit on the eve of the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie uprising.

Krste Petkov Misirkov was a philologist, journalist, historian and ethnographer from the region of Macedonia.

Dimitar Blagoev Nikolov was a Bulgarian political leader and philosopher. He was the founder of the Bulgarian left-wing political movement and of the first social-democratic party in the Balkans, the Marxist Bulgarian Social Democratic Party. Blagoev was also an important figure in the early history of Russian Marxism, and later founded and led the Bulgarian Communist Party. He was a prominent proponent of ideas for the establishment of a Balkan Federation. He is usually regarded and self-identified as a Bulgarian, and occasionally as a Macedonian Slav.

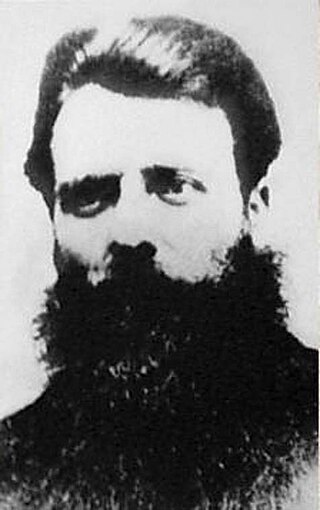

Damyan Yovanov Gruev was а Bulgarian teacher, revolutionary and insurgent leader in the Ottoman regions of Macedonia and Thrace. He was one of the six founders of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization. Per Macedonian historiography, he was an ethnic Macedonian. He is considered a national hero in Bulgaria and North Macedonia.

Gyorche Petrov Nikolov born Georgi Petrov Nikolov, was a Bulgarian teacher and revolutionary, one of the leaders of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO). He was its representative in Sofia, the capital of Principality of Bulgaria. As such he was also a member of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC), participating in the work of its governing body. During the Balkan Wars, Petrov was a Bulgarian army volunteer, and during the First World War, he was involved in the activity of the Bulgarian occupation authorities in Serbia and Greece. Subsequently, he participated in Bulgarian politics, but was eventually killed by the rivaling IMRO right-wing faction. According to the Macedonian historiography, he was an ethnic Macedonian.

Andrey Tasev Lyapchev (Tarpov) (Bulgarian: Андрей Тасев Ляпчев (Tърпов)) (30 November 1866 – 6 November 1933) was a Bulgarian Prime Minister in three consecutive governments.

The history of the Macedonian language refers to the developmental periods of current-day Macedonian, an Eastern South Slavic language spoken on the territory of North Macedonia. The Macedonian language developed during the Middle Ages from the Old Church Slavonic, the common language spoken by Slavic people.

Petar Poparsov or Petar Pop Arsov was a Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary, educator and one of the founders of the Internal Macedonian Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO). He is regarded as an ethnic Macedonian by the historiography in North Macedonia.

Macedonian nationalism is a general grouping of nationalist ideas and concepts among ethnic Macedonians that were first formed in the late 19th century among separatists seeking the autonomy of the region of Macedonia from the Ottoman Empire. The idea evolved during the early 20th century alongside the first expressions of ethnic nationalism among the Slavs of Macedonia. The separate Macedonian nation gained recognition during World War II when the Socialist Republic of Macedonia was created as part of Yugoslavia. Macedonian historiography has since established links between the ethnic Macedonians and various historical events and individual figures that occurred in and originated from Macedonia, which range from the Middle Ages up to the 20th century. Following the independence of the Republic of Macedonia in the late 20th century, issues of Macedonian national identity have become contested by the country's neighbours, as some adherents to aggressive Macedonian nationalism, called Macedonism, hold more extreme beliefs such as an unbroken continuity between ancient Macedonians, and modern ethnic Macedonians, and views connected to the irredentist concept of a United Macedonia, which involves territorial claims on a large portion of Greece and Bulgaria, along with smaller regions of Albania, Kosovo and Serbia.

The Macedonian Scientific Institute is a Bulgarian scientific organization, which studies the region of Macedonia and mostly the Macedonian Bulgarians.

Koprivlen is a village in Hadzhidimovo Municipality, in Blagoevgrad Province, Bulgaria.

Novo Leski is a village in Hadzhidimovo Municipality, in Blagoevgrad Province, Bulgaria.

Vasil Kostov Glavinov was a Bulgarian left-wing politician from Ottoman Macedonia, and an activist of the Bulgarian workers' movement.

Kosta S. Shahov was a Macedonian Bulgarian public figure, journalist, activist of the Young Macedonian Literary Society and the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee.

The Eastern South Slavic dialects form the eastern subgroup of the South Slavic languages. They are spoken mostly in Bulgaria and North Macedonia, and adjacent areas in the neighbouring countries. They form the so-called Balkan Slavic linguistic area, which encompasses the southeastern part of the dialect continuum of South Slavic.

Naum Tyufekchiev, born on June 29, 1864, in Resen, in the Ottoman Empire, was a Bulgarian and Macedonian revolutionary, explosives expert, tactician, and anarchist arms dealer. He was a member and leader of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO).