Eskimo is an exonym used to refer to two closely related Indigenous peoples: the Inuit and the Yupik of eastern Siberia and Alaska. A related third group, the Aleut, which inhabit the Aleutian Islands, are generally excluded from the definition of Eskimo. The three groups share a relatively recent common ancestor, and speak related languages belonging to the Eskaleut language family.

The Yupik are a group of indigenous or aboriginal peoples of western, southwestern, and southcentral Alaska and the Russian Far East. They are related to the Inuit and Iñupiat. Yupik peoples include the following:

The Iñupiat are a group of indigenous Alaskans whose traditional territory roughly spans northeast from Norton Sound on the Bering Sea to the northernmost part of the Canada–United States border. Their current communities include 34 villages across Iñupiat Nunaat, including seven Alaskan villages in the North Slope Borough, affiliated with the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation; eleven villages in Northwest Arctic Borough; and sixteen villages affiliated with the Bering Straits Regional Corporation. They often claim to be the first people of the Kauwerak.

The Eskaleut, Eskimo–Aleut or Inuit–Yupik–Unangan languages are a language family native to the northern portions of the North American continent and a small part of northeastern Asia. Languages in the family are indigenous to parts of what are now the United States (Alaska); Canada including Nunavut, Northwest Territories, northern Quebec (Nunavik), and northern Labrador (Nunatsiavut); Greenland; and the Russian Far East. The language family is also known as Eskaleutian, Eskaleutic or Inuit–Yupik–Unangan.

Siberian Yupiks, or Yuits, are a Yupik people who reside along the coast of the Chukchi Peninsula in the far northeast of the Russian Federation and on St. Lawrence Island in Alaska. They speak Central Siberian Yupik, a Yupik language of the Eskimo–Aleut family of languages.

Nunivak Island is a permafrost-covered volcanic island lying about 30 miles (48 km) offshore from the delta of the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers in the US state of Alaska, at a latitude of about 60°N. The island is 1,631.97 square miles (4,226.8 km2) in area, making it the second-largest island in the Bering Sea and eighth-largest island in the United States. It is 76.2 kilometers (47.3 mi) long and 106 kilometers (66 mi) wide. It has a population of 191 persons as of the 2010 census, down from 210 in 2000. The island's entire population lives in the north coast city of Mekoryuk.

The Yupik languages are a family of languages spoken by the Yupik peoples of western and south-central Alaska and Chukotka. The Yupik languages differ enough from one another that they are not mutually intelligible, although speakers of one of the languages may understand the general idea of a conversation of speakers of another of the languages. One of them, Sirenik, has been extinct since 1997.

Deg Hitʼan is a group of Athabaskan peoples in Alaska. Their native language is called Deg Xinag. They reside in Alaska along the Anvik River in Anvik, along the Innoko River in Shageluk, and at Holy Cross along the lower Yukon River.

Central Alaskan Yupʼik is one of the languages of the Yupik family, in turn a member of the Eskimo–Aleut language group, spoken in western and southwestern Alaska. Both in ethnic population and in number of speakers, the Central Alaskan Yupik people form the largest group among Alaska Natives. As of 2010 Yupʼik was, after Navajo, the second most spoken aboriginal language in the United States. Yupʼik should not be confused with the related language Central Siberian Yupik spoken in Chukotka and St. Lawrence Island, nor Naukan Yupik likewise spoken in Chukotka.

Inu-Yupiaq is a dance group at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks that performs a fusion of Iñupiaq and Yup’ik Eskimo motion dance.

The Yupiit or Yupiat, also Central Alaskan Yup'ik, are an Alaska Native people of western and southwestern Alaska, ranging from the Norton Sound down along the coast of the Bering Sea to Bristol Bay as far south as the Alaska Peninsula at Naknek River and Egegik Bay. They are also known as Cup'ik by the Chevak Cup'ik-speaking people of Chevak and Cup'ig for the Nunivak Cup'ig-speaking people of Nunivak Island.

Alaska Native cultures are rich and diverse, and their art forms are representations of their history, skills, tradition, adaptation, and nearly twenty thousand years of continuous life in some of the most remote places on earth. These art forms are largely unseen and unknown outside the state of Alaska, due to distance from the art markets of the world.

Nunivak Cup'ig or just Cup'ig is a language or separate dialect of Central Alaskan Yup'ik spoken in Central Alaska at the Nunivak Island by Nunivak Cup'ig people. The letter "c" in the Yup’ik alphabet is equivalent to the English alphabet "ch".

Chevak Cupʼik or just Cupʼik is a subdialect of Hooper Bay–Chevak dialect of Yupʼik spoken in southwestern Alaska in the Chevak by Chevak Cupʼik Eskimos. The speakers of the Chevak subdialect used for themselves as Cupʼik, but the speakers of the Hooper Bay subdialect used for themselves as Yupʼik, as in the Yukon-Kuskokwim dialect.

Qargi, Qasgi or Qasgiq, Qaygiq, Kashim, Kariyit, a traditional large semi-subterranean men's community house' of the Yup'ik and Inuit, also Deg Hit'an Athabaskans, was used for public and ceremonial occasions and as a men’s residence. The Qargi was the place where men built their boats, repaired their equipment, took sweat baths, educated young boys, and hosted community dances. Here people learned their oral history, songs and chants. Young boys and men learned to make tools and weapons while they listened to the traditions of their forefathers.

A kuspuk is a hooded overshirt with a large front pocket commonly worn among Alaska Natives. Kuspuks are tunic-length, falling anywhere from below the hips to below the knees. The bottom portion of kuspuks worn by women may be gathered and akin to a skirt. Kuspuks tend to be pullover garments, though some have zippers.

Yup'ik masks are expressive shamanic ritual masks made by the Yup'ik people of southwestern Alaska. Also known as Cup'ik masks for the Chevak Cup'ik dialect speaking people of Chevak and Cup'ig masks for the Nunivak Cup'ig dialect speaking people of Nunivak Island. They are typically made of wood, and painted with few colors. The Yup'ik masks were carved by men or women, but mainly were carved by the men. The shamans (angalkuq) were the ones that told the carvers how to make the masks. Yup'ik masks could be small three-inch finger masks or maskettes, but also ten-kilo masks hung from the ceiling or carried by several people. These masks are used to bring the person wearing it luck and good fortune in hunts. Over the long winter darkness dances and storytelling took place in the qasgiq using these masks. They most often create masks for ceremonies but the masks are traditionally destroyed after being used. After Christian contact in the late nineteenth century, masked dancing was suppressed, and today it is not practiced as it was before in the Yup'ik villages.

Yup'ik dance or Yuraq, also Yuraqing is a traditional Inuit style dancing form usually performed to songs in Yup'ik, with dances choreographed for specific songs which the Yup'ik people of southwestern Alaska. Also known as Cup'ik dance for the Chevak Cup'ik dialect speaking Inuit of Chevak and Cup'ig dance for the Nunivak Cup'ig dialect speaking Inuit of Nunivak Island. Yup'ik dancing is set up in a very specific and cultural format. Typically, the men are in the front, kneeling and the women stand in the back. The drummers are in the very back of the dance group. Dance is the heart of Yup’ik spiritual and social life. Traditional dancing in the qasgiq is a communal activity in Yup’ik tradition. The mask (kegginaquq) was a central element in Yup'ik ceremonial dancing.

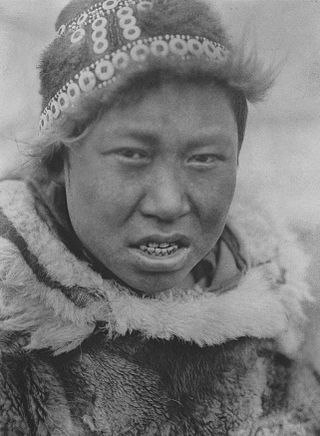

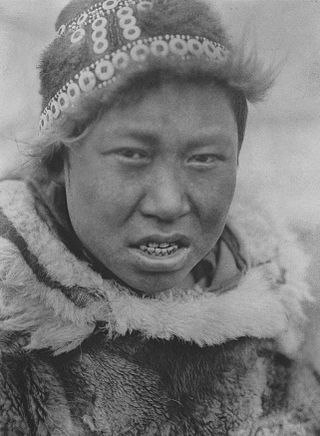

Yup'ik clothing refers to the traditional Eskimo-style clothing worn by the Yupik people of southwestern Alaska.

Yup'ik cuisine refers to the Eskimo style traditional subsistence food and cuisine of the Yup'ik people from the western and southwestern Alaska. Also known as Cup'ik cuisine for the Chevak Cup'ik dialect speaking Eskimos of Chevak and Cup'ig cuisine for the Nunivak Cup'ig dialect speaking Eskimos of Nunivak Island. This cuisine is traditionally based on meat from fish, birds, sea and land mammals, and normally contains high levels of protein. Subsistence foods are generally considered by many to be nutritionally superior superfoods. Yup’ik diet is different from Alaskan Inupiat, Canadian Inuit, and Greenlandic diets. Fish as food are primary food for Yup'ik Eskimos. Both food and fish called neqa in Yup'ik. Food preparation techniques are fermentation and cooking, also uncooked raw. Cooking methods are baking, roasting, barbecuing, frying, smoking, boiling, and steaming. Food preservation methods are mostly drying and less often frozen. Dried fish is usually eaten with seal oil. The ulu or fan-shaped knife used for cutting up fish, meat, food, and such.