The 1929 Atlantic hurricane season was among the least active Atlantic hurricane seasons on record, with only five tropical cyclones forming. Three of them intensified into a hurricane, with one strengthening further into a major hurricane. The first tropical cyclone of the season developed in the Gulf of Mexico on June 27. Becoming a hurricane on June 28, the storm struck Texas, bringing strong winds to a large area. Three fatalities were reported, while damage was conservatively estimated at $675,000 (1929 USD).

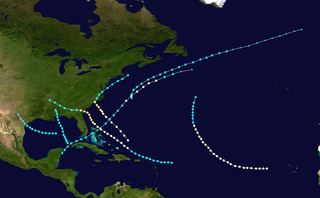

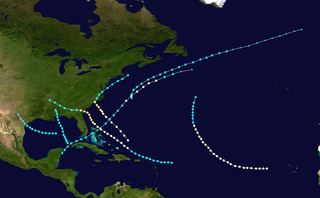

The 1927 Atlantic hurricane season was a relatively inactive season, with eight tropical storms, four of which became hurricanes. One of these became a major hurricane – Category 3 or higher on the modern day Saffir–Simpson scale. The first system, a tropical depression, developed on August 13, while the final cyclone, a tropical storm, merged with a cold front on November 21. No hurricane made landfall in the United States, in contrast to the four that struck the U.S. in the previous season.

The 1919 Atlantic hurricane season was among the least active hurricane seasons in the Atlantic on record, featuring only five tropical storms. Of those five tropical cyclones, two of them intensified into a hurricane, with one strengthening into a major hurricane Two tropical depressions developed in the month of June, both of which caused negligible damage. A tropical storm in July brought minor damage to Pensacola, Florida, but devastated a fleet of ships. Another two tropical depressions formed in August, the first of which brought rainfall to the Lesser Antilles.

The 1903 Atlantic hurricane season featured seven hurricanes, the most in an Atlantic hurricane season since 1893. The first tropical cyclone was initially observed in the western Atlantic Ocean near Puerto Rico on July 21. The tenth and final system transitioned into an extratropical cyclone well northwest of the Azores on November 25. These dates fall within the period with the most tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic. Six of the ten tropical cyclones existed simultaneously.

The 1898 Atlantic hurricane season marked the beginning of the Weather Bureau operating a network of observation posts across the Caribbean Sea to track tropical cyclones, established primarily due to the onset of the Spanish–American War. A total of eleven tropical storms formed, five of which intensified into a hurricane, according to HURDAT, the National Hurricane Center's official database. Further, one cyclone strengthened into a major hurricane. However, in the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 has been estimated. The first system was initially observed on August 2 near West End in the Bahamas, while the eleventh and final storm dissipated on November 4 over the Mexican state of Veracruz.

The 1897 Atlantic hurricane season was an inactive season, featuring only six known tropical cyclones, four of which made landfall. There were three hurricanes, none of which strengthened into major hurricanes, which are Category 3 or higher on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. The first system was initially observed south of Cape Verde on August 31, an unusually late date. The storm was the strongest of the season, peaking as a Category 2 hurricane with winds of 100 mph (155 km/h). While located well north of the Azores, rough seas by the storm sunk a ship, killing all 45 crewmen. A second storm was first spotted in the Straits of Florida on September 10. It strengthened into a hurricane and tracked northwestward across the Gulf of Mexico, striking Louisiana shortly before dissipating on September 13. This storm caused 29 deaths and $150,000 (1897 USD) in damage.

The 1895 Atlantic hurricane season was a fairly inactive one, featuring only six known tropical cyclones, although each of them made landfall. Of those six systems, only two intensified a hurricane, while none of those strengthened into a major hurricane. However, in the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 has been estimated.

The 1894 Atlantic hurricane season ran through the summer and the first half of fall in 1894. The 1894 season was a fairly inactive one, with seven storms forming, five of which became hurricanes.

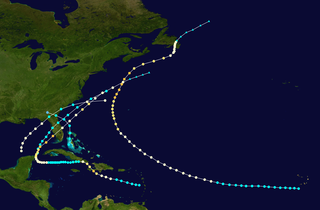

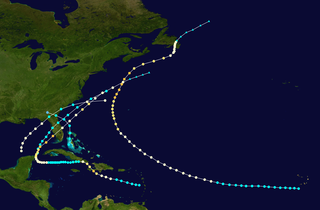

The 1893 Atlantic hurricane season ran through the summer and the first half of fall in 1893. The 1893 season was fairly active, with 12 tropical storms forming, 10 of which became hurricanes. Of those, five became major hurricanes. This season proved to be a very deadly season, with two different hurricanes each causing over 2,000 deaths in the United States; at the time, the season was the deadliest in U.S. history. The season was one of two seasons on record to see four Atlantic hurricanes active simultaneously, along with the 1998 Atlantic hurricane season. Additionally, August 15, 1893 was the only time since the advent of modern record keeping that three storms have formed on the same day until 2020 saw Wilfred, Alpha, and Beta forming on the same day; and for the first time, there were two high-intensity hurricanes simultaneously in one month of August, and this was not repeated until the year 2023.

The 1891 Atlantic hurricane season began during the summer and ran through the late fall of 1891. The season had ten tropical cyclones. Seven of these became hurricanes; one becoming a major Category 3 hurricane.

The 1880 Atlantic hurricane season ran through the summer and fall of 1880. This is the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. In the 1880 Atlantic season there were two tropical storms, seven hurricanes, and two major hurricanes (Category 3+). However, in the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 has been estimated. Of the known 1880 cyclones, Hurricane Six was first documented in 1995 by José Fernández-Partagás and Henry Díaz. They also proposed large changes to the known tracks of several other storms for this year and 're-instated' Hurricane Ten to the database. A preliminary reanalysis by Michael Chenoweth, published in 2014, found thirteen storms, nine hurricanes, and four major hurricanes.

The 1887 Atlantic hurricane season was the most active Atlantic hurricane season on record at the time in terms of the number of known tropical storms that had formed, with 19. This total has since been equaled or surpassed multiple times. The 1887 season featured five off-season storms, with tropical activity occurring as early as May, and as late as December. Eleven of the season's storms attained hurricane status, while two of those became major hurricanes. It is also worthy of note that the volume of recorded activity was documented largely without the benefit of modern technology. Consequently, tropical cyclones during this era that did not approach populated areas or shipping lanes, especially if they were relatively weak and of short duration, may have remained undetected. Thus, historical data on tropical cyclones from this period may not be comprehensive, with an undercount bias of zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 estimated. The first system was initially observed on May 15 near Bermuda, while the final storm dissipated on December 12 over Costa Rica.

The 1870 Atlantic hurricane season marked the beginning of Father Benito Viñes investigating tropical cyclones, inspired by two hurricanes that devastated Cuba that year; Viñes consequently became a pioneer in studying and forecasting such storms. The season featured 11 known tropical cyclones, 10 of which became a hurricane, while 2 of those intensified into major hurricanes. However, in the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 has been estimated.

The 1885 Atlantic hurricane season ran through the summer and the first half of fall in 1885. This is the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. In 1885 there were two tropical storms and six hurricanes in the Atlantic basin. However, in the absence of modern satellite monitoring and remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 has been estimated.

The 1881 Atlantic hurricane season ran through the summer and early fall of 1881. This is the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. In the 1881 Atlantic season there were three tropical storms and four hurricanes, none of which became major hurricanes. However, in the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 has been estimated. Of the known 1881 cyclones, Hurricane Three and Tropical Storm Seven were both first documented in 1996 by Jose Fernandez-Partagas and Henry Diaz. They also proposed changes to the known tracks of Hurricane Four and Hurricane Five.

The 1854 Atlantic hurricane season featured five known tropical cyclones, three of which made landfall in the United States. At one time, another was believed to have existed near Galveston, Texas in September, but HURDAT – the official Atlantic hurricane database – now excludes this system. The first system, Hurricane One, was initially observed on June 25. The final storm, Hurricane Five, was last observed on October 22. These dates fall within the period with the most tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic. No tropical cyclones during this season existed simultaneously. One tropical cyclone has a single known point in its track due to a sparsity of data.

The 1853 Atlantic hurricane season featured eight known tropical cyclones, none of which made landfall. Operationally, a ninth tropical storm was believed to have existed over the Dominican Republic on November 26, but HURDAT – the official Atlantic hurricane database – now excludes this system. The first system, Tropical Storm One, was initially observed on August 5. The final storm, Hurricane Eight, was last observed on October 22. These dates fall within the period with the most tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic. At two points during the season, pairs of tropical cyclones existed simultaneously. Four of the cyclones only have a single known point in their tracks due to a sparsity of data, so storm summaries for those systems are unavailable.

The 1873 Atlantic hurricane season was quiet, featuring only five known tropical cyclones, but all of them made landfall, causing significant impacts in some areas of the basin. Of these five systems, three intensified into a hurricane, while two of those attained major hurricane status. However, in the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 has been estimated.

The 1863 Atlantic hurricane season featured five landfalling tropical cyclones. In the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 has been estimated. There were seven recorded hurricanes and no major hurricanes, which are Category 3 or higher on the modern day Saffir–Simpson scale. Of the known 1863 cyclones, seven were first documented in 1995 by José Fernández-Partagás and Henry Diaz, while the ninth tropical storm was first documented in 2003. These changes were largely adopted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic hurricane reanalysis in their updates to the Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT), with some adjustments.

The 1859 Atlantic hurricane season featured seven hurricanes, the most recorded during an Atlantic hurricane season until 1870. However, in the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 has been estimated. Of the eight known 1859 cyclones, five were first documented in 1995 by Jose Fernandez-Partagás and Henry Diaz, which was largely adopted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic hurricane reanalysis in their updates to the Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT), with some adjustments. HURDAT is the official source for hurricane data such as track and intensity, although due to sparse records, listings on some storms are incomplete.