Aliyah is the immigration of Jews from the diaspora to, historically, the geographical Land of Israel, which is in the modern era chiefly represented by the State of Israel. Traditionally described as "the act of going up", moving to the Land of Israel or "making aliyah" is one of the most basic tenets of Zionism. The opposite action—emigration by Jews from the Land of Israel—is referred to in the Hebrew language as yerida. The Law of Return that was passed by the Israeli parliament in 1950 gives all diaspora Jews, as well as their children and grandchildren, the right to relocate to Israel and acquire Israeli citizenship on the basis of connecting to their Jewish identity.

The history of the Jews in the Soviet Union is inextricably linked to much earlier expansionist policies of the Russian Empire conquering and ruling the eastern half of the European continent already before the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. "For two centuries – wrote Zvi Gitelman – millions of Jews had lived under one entity, the Russian Empire and [its successor state] the USSR. They had now come under the jurisdiction of fifteen states, some of which had never existed and others that had passed out of existence in 1939." Before the revolutions of 1989 which resulted in the end of communist rule in Central and Eastern Europe, a number of these now sovereign countries constituted the component republics of the Soviet Union.

The Jackson–Vanik amendment to the Trade Act of 1974 is a 1974 provision in United States federal law intended to affect U.S. trade relations with countries with non-market economies that restrict freedom of Jewish emigration and other human rights. The amendment is contained in the Trade Act of 1974 which passed both houses of the United States Congress unanimously, and signed by President Gerald Ford into law, with the adopted amendment, on January 3, 1975. Over time, a number of countries were granted conditional normal trade relations subject to annual review, and a number of countries were liberated from the amendment.

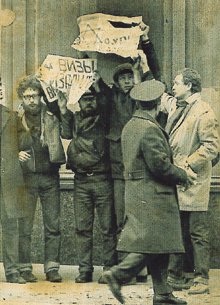

Refusenik was an unofficial term for individuals—typically, but not exclusively, Soviet Jews—who were denied permission to emigrate, primarily to Israel, by the authorities of the Soviet Union and other countries of the Eastern bloc. The term refusenik is derived from the "refusal" handed down to a prospective emigrant from the Soviet authorities.

Yosef Mendelevitch, was a refusenik from the former Soviet Union, also known as a "Prisoner of Zion" and now a politically unaffiliated rabbi living in Jerusalem who gained fame for his adherence to Judaism and public attempts to emigrate to Israel at a time when it was against the law in the USSR.

The Dymshits–Kuznetsov aircraft hijacking affair, also known as The First Leningrad Trial or Operation Wedding, was an attempt to take an empty civilian aircraft on 15 June 1970 by a group of 16 Soviet refuseniks in order to escape to the West. Even though the attempt was unsuccessful, it was a notable event in the course of the Cold War because it drew international attention to human rights violations in the Soviet Union and resulted in the temporary loosening of emigration restrictions.

Russian Americans are Americans of full or partial Russian ancestry. The term can apply to recent Russian immigrants to the United States, as well as to those who settled in the 19th century Russian possessions in northwestern America. Russian Americans comprise the largest Eastern European and East Slavic population in the U.S., the second-largest Slavic population generally, the nineteenth-largest ancestry group overall, and the eleventh-largest from Europe.

Nativ, or officially Lishkat Hakesher or The Liaison Bureau, is an Israeli governmental liaison organization that maintained contact with Jews living in the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War and encouraged aliyah, immigration to Israel.

Nehemiah Levanon was an Israeli intelligence agent, diplomat, head of the aliyah program Nativ, and a founder of kibbutz Kfar Blum. Originally a native of Latvia, he immigrated to the Mandatory Palestine in 1938. After Israel's independence in 1948, Levanon served in a variety of roles to encourage the well-being and emigration of Soviet Jewry. Due to the covert nature of his work, Levanon's decades of service were largely unknown until after his retirement, during the last days of the Soviet Union.

HIAS is a Jewish American nonprofit organization that provides humanitarian aid and assistance to refugees. It was originally established in 1881 to aid Jewish refugees. In 1975, the State Department asked HIAS to aid in resettling 3,600 Vietnam refugees. Since that time, the organization continues to provide support for refugees of all nationalities, religions, and ethnic origins. The organization works with people whose lives and freedom are believed to be at risk due to war, persecution, or violence. HIAS has offices in the United States and across Latin America, Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. Since its inception, HIAS has helped resettle more than 4.5 million people.

The 1990s post-Soviet aliyah began en masse in the late 1980s when the government of Mikhail Gorbachev opened the borders of the USSR and allowed Jews to leave the country for Israel.

Ida Yakovlevna Nudel was a Soviet-born Israeli refusenik and activist. She was known as the "Guardian Angel" for her efforts to help the "Prisoners of Zion" in the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Jewry movement was an international human rights campaign that advocated for the right of Jews in the Soviet Union to emigrate. The movement's participants were most active in the United States and in the Soviet Union. Those who were denied permission to emigrate were often referred to by the term Refusenik.

The Schoenau ultimatum was a hostage-taking incident in Marchegg, Austria by the Palestinian militant group As-Sa'iqa in 1973. At the time Vienna was a transit point for Russian Jews, the largest population of Jews remaining in Europe. The Schoenau ultimatum focused attention away from Egyptian and Syrian military build-up and their planned attack that would come to be known as the Yom Kippur War.

The National Coalition Supporting Eurasian Jewry (NCSEJ), formerly the National Council for Soviet Jewry (NCSJ), is an organization in the United States which advocates for the freedoms and rights of Jews in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, the Baltic States, and Eurasia. Emerging from the American Jewish Conference on Soviet Jewry, now with a paid staff, it played an important role in the Soviet Jewry movement, including such landmark legislation as Jackson–Vanik amendment. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., it is now an umbrella organization of about 50 national organizations and 300+ local federations, community councils and committees.

Georgian Jews in Israel, also known as Gruzinim, are immigrants and descendants of the immigrants of the Georgian Jewish communities, who now reside within the state of Israel. They number around 75,000 to 80,000.

Freedom Sunday for Soviet Jews was the title of a national march and political rally that was held on December 6, 1987 in Washington, D.C. An estimated 250,000 participants gathered on the National Mall, calling for the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, to extend his policy of Glasnost to Soviet Jews by putting an end to their forced assimilation and allowing their emigration from the Soviet Union. The rally was organized by a broad-based coalition of Jewish organizations. At the time, it was reported to be the "largest Jewish rally ever held in Washington."

David Jonathan Waksberg, was a leading activist in the Soviet Jewry Movement during the 1980s and early 1990s. In the 1970s he became involved in the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry. In the early 1980s he moved to California and began working for the Bay Area Council for Soviet Jews, first as Assistant Director, and later as executive director. He initiated public and political activities on behalf of Soviet Jewry, supervised research and monitoring of their welfare and coordinated financial, medical and legal aid to Refuseniks and Prisoners of Conscience trapped in the Soviet Union. During his first visit to the USSR in 1982, Waksberg was arrested and detained by the KGB while attempting, along with refusenik Yuri Chernyak, to visit Kiev refusenik Lev Elbert. He organized numerous protest demonstrations and vigils to raise public awareness of the plight of Jews in the USSR. In 1985 Waksberg became National Vice-President of BACSJ's umbrella organization, the Union of Councils for Soviet Jews. Waksberg frequently visited Jewish communities of the Soviet Union and the former Soviet states and coordinated briefings of the American travelers interested in visiting those communities. In 1990 Waksberg took on the role of Director of the Center for Jewish Renewal, newly established by UCSJ. The mission of the CJR was to promote the renewal and development of Jewish life in the USSR and the emigration rights, human rights and resettlement needs of Jews in the Former Soviet Union. The CJR established a network of human rights and emigration bureaus in major cities of the former Soviet Union. In mid-1990s Waksberg was a member of Bay Area Council's Board of Directors and served as Director of Development and Communication of the UCSJ. Since 2007 Waksberg has served as Chief Executive Officer of Jewish LearningWorks.

Russian Jews in Israel are immigrants and descendants of the immigrants of the Russian Jewish communities, who now reside within the State of Israel. They were around 900,000 in 2007. This refers to all post-Soviet Jewish diaspora groups, not only Russian Jews, but also Mountain Jews, Crimean Karaites, Krymchaks, Bukharan Jews, and Georgian Jews.

Bukharan Jews in Israel, also known as the Bukharim, refers to immigrants and descendants of the immigrants of the Bukharan Jewish communities, who now reside within the state of Israel.