The Polish People's Party is an agrarian political party in Poland. It is currently led by Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz.

The Polish United Workers' Party, commonly abbreviated to PZPR, was the communist party which ruled the Polish People's Republic as a one-party state from 1948 to 1989. The PZPR had led two other legally permitted subordinate minor parties together as the Front of National Unity and later Patriotic Movement for National Rebirth. Ideologically, it was based on the theories of Marxism-Leninism, with a strong emphasis on left-wing nationalism. The Polish United Workers' Party had total control over public institutions in the country as well as the Polish People's Army, the UB and SB security agencies, the Citizens' Militia (MO) police force and the media.

Wojciech Witold Jaruzelski was a Polish military general, politician and de facto leader of the Polish People's Republic from 1981 until 1989. He was the First Secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party between 1981 and 1989, making him the last leader of the Polish People's Republic. Jaruzelski served as Prime Minister from 1981 to 1985, the Chairman of the Council of State from 1985 to 1989 and briefly as President of Poland from 1989 to 1990, when the office of President was restored after 37 years. He was also the last commander-in-chief of the Polish People's Army, which in 1990 became the Polish Armed Forces.

From 1989 through 1991, Poland engaged in a democratic transition which put an end to the Polish People's Republic and led to the foundation of a democratic government, known as the Third Polish Republic, following the First and Second Polish Republic. After ten years of democratic consolidation, Poland joined NATO in 1999 and the European Union on 1 May 2004.

The Polish Round Table Talks took place in Warsaw, Poland from 6 February to 5 April 1989. The government initiated talks with the banned trade union Solidarność and other opposition groups in an attempt to defuse growing social unrest.

Presidential elections were held in Poland on 25 November 1990, with a second round on 9 December. They were the first direct presidential elections in the history of Poland, and the first free presidential elections since the May Coup of 1926. Before World War II, presidents were elected by the Sejm. From 1952 to 1989—the bulk of the Communist era—the presidency did not exist as a separate institution, and most of its functions were fulfilled by the State Council of Poland, whose chairman was considered the equivalent of a president.

Zbigniew Stefan Messner was a Polish communist politician and economist. His ancestors were of German Polish descent who had assimilated into Polish society. In 1972, he became Professor of Karol Adamiecki University of Economics in Katowice. In the 1980s, Messner held numerous high ranking posts within communist party apparatus. He was a member of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR) from 1981 to 1990, when PZPR was dissolved, member of the PZPR Politburo from 1981 to 1988, Deputy Prime Minister from 1983 to 1985, member of Sejm from 1985 to 1989, Prime Minister of Polish People's Republic from 1985 to 1988 and member of the State Council of the Polish People's Republic from 1988 to 1989. Additionally in the 1960s Messner was the chairman of Piast Gliwice football club.

Poland has a multi-party political system. On the national level, Poland elects the head of state – the president – and a legislature. There are also various local elections, referendums and elections to the European Parliament.

The history of Poland from 1945 to 1989 spans the period of Marxist–Leninist regime in Poland after the end of World War II. These years, while featuring general industrialization, urbanization and many improvements in the standard of living,[a1] were marred by early Stalinist repressions, social unrest, political strife and severe economic difficulties. Near the end of World War II, the advancing Soviet Red Army, along with the Polish Armed Forces in the East, pushed out the Nazi German forces from occupied Poland. In February 1945, the Yalta Conference sanctioned the formation of a provisional government of Poland from a compromise coalition, until postwar elections. Joseph Stalin, the leader of the Soviet Union, manipulated the implementation of that ruling. A practically communist-controlled Provisional Government of National Unity was formed in Warsaw by ignoring the Polish government-in-exile based in London since 1940.

The Solidarity Citizens' Committee, also known as Citizens' Electoral Committee and previously named the Citizens' Committee with Lech Wałęsa, was an initially semi-legal political organisation of the democratic opposition in Communist Poland.

The Citizens' Movement for Democratic Action was a political faction in Poland coalescing several members of the Solidarity Citizens' Committee.

The Alliance of Democrats is a Polish centre-left party. Initially formed in 1937, the party underwent a revival in 2009, when it was joined by liberal politician Paweł Piskorski, formerly a member of the Civic Platform.

Communism in Poland can trace its origins to the late 19th century: the Marxist First Proletariat party was founded in 1882. Rosa Luxemburg (1871–1919) of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania party and the publicist Stanisław Brzozowski (1878–1911) were important early Polish Marxists.

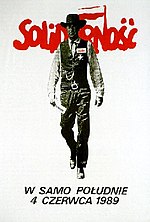

Solidarity, a Polish non-governmental trade union, was founded on August 14, 1980, at the Lenin Shipyards by Lech Wałęsa and others. In the early 1980s, it became the first independent labor union in a Soviet-bloc country. Solidarity gave rise to a broad, non-violent, anti-Communist social movement that, at its height, claimed some 9.4 million members. It is considered to have contributed greatly to the Fall of Communism.

The United People's Party was an agrarian socialist political party in the People's Republic of Poland. It was formed on 27 November 1949 from the merger of the pro-Communist Stronnictwo Ludowe party with remnants of the independent Polish People's Party of Stanisław Mikołajczyk.

Parliamentary elections were held in Poland on 20 January 1957. They were the second election to the Sejm – the unicameral parliament of the People's Republic of Poland, and the third ever in the history of Communist Poland. It took place during the liberalization period, following Władysław Gomułka's ascension to power. Although conducted in a more liberal atmosphere than previous elections, they were far from free. Voters had the option of voting against some official candidates; de facto having a small chance to express a vote of no confidence against the government and the ruling Communist Polish United Workers Party. However, as in all Communist countries, there was no opportunity to elect any true opposition members to the Sejm. The elections resulted in a predictable victory for the Front of National Unity, dominated by the PZPR.

Parliamentary elections were held in Poland on 26 October 1952. They were the first elections to the Sejm, the parliament of the Polish People's Republic. The official rules for the elections were outlined in the new Constitution of the Polish People's Republic and lesser acts. The Front of National Unity received 99.8% of the vote and won every seat in the Sejm, a result that was to be repeated in parliamentary elections until 1989.

Patriotyczny Ruch Odrodzenia Narodowego was a Polish popular front that ruled the Polish People's Republic. It was created in the aftermath of the martial law in Poland (1982). Gathering various pro-communist and pro-government organizations, it was attempted to show unity and support for the government and the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR). PRON was created in July 1982 and dissolved in November 1989.

Parliamentary elections were held in Poland on 13 October 1985. According to the Constitution of 1952 the elections should have been held every 4 years, that is in the spring of 1984, but since the internal political situation was still considered "unstable" even after the repealing in 1983 of the Martial Law, the Sejm voted to extend its own term at first indefinitely and then until August 31, 1985, fixing the elections to be held not beyond the end of 1985. As was the case in previous elections, only candidates approved by the Communist regime were permitted on the ballot. The outcome was thus not in doubt, nevertheless the regime was hoping for a high turnout, which it could then claim as evidence of strong support for the government among the population. The opposition from the Solidarity movement called for a boycott of the elections. According to official figures 78.9% of the electorate turned out to vote. This turnout, while relatively high, was much lower than the nearly 100% turnout which was reported in previous elections.

Warsaw I, officially known as Constituency no. 19, is one of the 41 constituencies of the Sejm, the lower house of the Parliament of Poland, the national legislature of Poland. The constituency was established as Constituency no. 1 in 1991 following the re-organisation of constituencies across Poland. It was renamed Sejm Constituency no. 19 in 2001 following another nationwide re-organisation of constituencies. It is conterminous with the city of Warsaw. Electors living abroad or working aboard ships and oil rigs are included in this constituency. The constituency currently elects 20 of the 460 members of the Sejm using the open party-list proportional representation electoral system. At the 2023 parliamentary election it had 1,993,723 registered electors.