Even before attaining its independence from Spain, Cuba had several constitutions either proposed or adopted by insurgents as governing documents for territory they controlled during their war against Spain. Cuba has had several constitutions since winning its independence. The first constitution since the Cuban Revolution was drafted in 1976 and has since been amended. In 2018, Cuba became engaged in a major revision of its constitution. The current constitution was then enacted in 2019.

The substantive and procedural laws of Cuba were based on Spanish Civil laws and influenced by the principles of Marxism-Leninism after that philosophy became the government's guiding force. Cuba's most recent Constitution was enacted in 2019.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) rights in Cuba have significantly varied throughout modern history. Cuba is now considered generally progressive, with vast improvements in the 21st century for such rights. Following the 2022 Cuban Family Code referendum, there is legal recognition of the right to marriage, unions between people of the same sex, same-sex adoption and non-commercial surrogacy as part of one of the most progressive Family Codes in Latin America. Until the 1990s, the LGBT community was marginalized on the basis of heteronormativity, traditional gender roles, politics and strict criteria for moralism. It was not until the 21st century that the attitudes and acceptance towards LGBT people changed to be more tolerant.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Portugal since 5 June 2010. The XVIII Constitutional Government of Portugal under Prime Minister José Sócrates introduced a bill for legalization in December 2009. It was passed by the Assembly of the Republic in February 2010, and was declared legally valid by the Portuguese Constitutional Court in April 2010. On 17 May 2010, President Aníbal Cavaco Silva ratified the law, making Portugal the sixth country in Europe and the eighth country in the world to allow same-sex marriage nationwide. The law was published in the Diário da República on 31 May and became effective on 5 June 2010.

The Constitutional Court is the supreme interpreter of the Spanish Constitution, with the power to determine the constitutionality of acts and statutes made by any public body, central, regional, or local in Spain. It is defined in Part IX of the Constitution of Spain, and further governed by Organic Laws 2/1979, 8/1984, 4/1985, 6/1988, 7/1999 and 1/2000. The court is the "supreme interpreter" of the Constitution, but since the court is not a part of the Spanish Judiciary, the Supreme Court is the highest court for all judicial matters.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Costa Rica since May 26, 2020 as a result of a ruling by the Supreme Court of Justice. Costa Rica was the first country in Central America to recognize and perform same-sex marriages.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Ecuador since 8 July 2019 in accordance with a Constitutional Court ruling issued on 12 June 2019 that the ban on same-sex marriage was unconstitutional under the Constitution of Ecuador. The ruling took effect upon publication in the government gazette on 8 July. Ecuador became the fifth country in South America to allow same-sex couples to marry, after Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay and Colombia, but adoption by married couples remains restricted to opposite-sex couples. The country has also recognized same-sex civil unions since 2008.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Cuba since 27 September 2022, after a majority of voters approved the legalization of same-sex marriage at a referendum two days prior. The Constitution of Cuba prohibited same-sex marriage until 2019, and in May 2019 the government announced plans to legalize same-sex marriage. A draft family code containing provisions allowing same-sex couples to marry and adopt was approved by the National Assembly of People's Power on 21 December 2021. The text was under public consultation until 6 June 2022, and was approved by the Assembly on 22 July 2022. The measure was approved by two-thirds of voters in a referendum held on 25 September 2022. President Miguel Díaz-Canel signed the new family code into law on 26 September, and it took effect upon publication in the Official Gazette the following day.

The Constitution of Ecuador is the supreme law of Ecuador. The current constitution has been in place since 2008. It is the country's 20th constitution.

Bolivia has recognised same-sex civil unions since 20 March 2023 in accordance with a ruling from the Plurinational Constitutional Court. The court ruled on 22 June 2022 that the Civil Registry Service (SERECI) was obliged to recognise civil unions for same-sex couples and urged the Legislative Assembly to pass legislation recognising same-sex unions. The court ruling went into effect upon publication on 20 March 2023. The ruling made Bolivia the seventh country in South America to recognise same-sex unions.

El Salvador does not recognize same-sex marriage, civil unions or any other legal union for same-sex couples. A proposal to constitutionally ban same-sex marriage and adoption by same-sex couples was rejected twice in 2006, and once again in April 2009 after the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) refused to grant the measure the four votes it needed to be ratified.

Miguel Mario Díaz-Canel y Bermúdez is a Cuban politician and engineer who is the 3rd and current First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba. As First Secretary, he is the most powerful person in the Cuban government. Díaz-Canel succeeds the brothers Fidel and Raúl Castro, making him the first non-Castro leader of Cuba since the revolution.

The Constitution of Costa Rica is the supreme law of Costa Rica. At the end of the 1948 Costa Rican Civil War, José Figueres Ferrer oversaw the Costa Rican Constitutional Assembly, which drafted the document. It was approved on 1949 November 7. Several older constitutions had been in effect starting from 1812, with the most recent former constitution ratified in 1871. The Costa Rican Constitution is remarkable in that in its Article 12 abolished the Costa Rican military, making it the second nation after Japan to do so by law. Another unusual clause is an amendment asserting the right to live in a healthy natural environment.

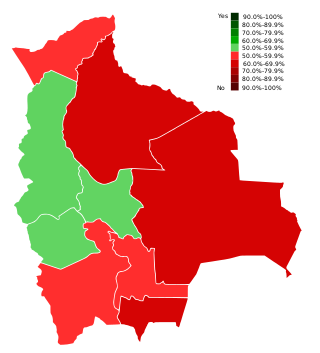

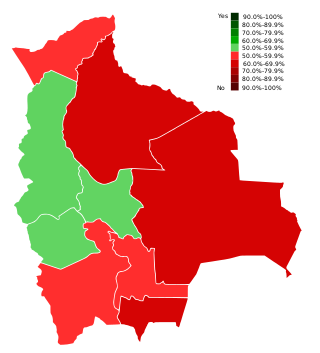

A constitutional referendum was held in Bolivia on Sunday, 21 February 2016. The proposed constitutional amendments would have allowed the president and vice president to run for a third consecutive term under the 2009 Constitution. The proposal was voted down by a 51.3% majority.

This is a list of notable events in the history of LGBT rights that took place in the year 2018.

Same-sex unions are currently not recognized in Honduras. Since 2005, the Constitution of Honduras has explicitly banned same-sex marriage. In January 2022, the Supreme Court dismissed a challenge to this ban, but a request for the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to review whether the ban violates the American Convention on Human Rights is pending. A same-sex marriage bill was introduced to Congress in May 2022.

The Constitutional Convention was the constituent body of the Republic of Chile in charge of drafting a new Political Constitution of the Republic after the approval of the national plebiscite held in October 2020. Its creation and regulation were carried out through Law No. 21,200, published on 24 December 2019, which amended the Political Constitution of the Republic to include the process of drafting a new constitution. The body met for the first time on 4 July 2021. Chilean President Sebastian Piñera said, "This Constitutional Convention must, within a period of 9 months, extendable for an additional 3 months, draft and approve a new constitution for Chile, which must be ratified by the citizens through a plebiscite." It ended its functions and declared itself dissolved on 4 July 2022.

The recognition of same-sex unions varies by country.

A referendum was held on 25 September 2022 in Cuba to approve amendments to the Family Code of the Cuban Constitution. The referendum passed, greatly strengthening gender equality, legalizing same-sex marriage, same-sex adoption, and altruistic surrogacy, and affirming a wide range of rights and protections for women, children, the elderly and people with disabilities. Following the referendum, Cuba's family policies have been described as among the most progressive in Latin America.

A constitutional referendum was held in Ecuador on 5 February 2023, alongside local elections. The binding consultation was called on 29 November 2022 by President Guillermo Lasso. Voters were asked to approve or reject a total of eight questions surrounding changes to the Constitution of Ecuador. Soon after the referendum, Reuters, Al Jazeera, CNN en Español and the Financial Times projected the failure of all eight of its proposals, with president Guillermo Lasso eventually conceding defeat. Turnout for the referendum was estimated at 80.74%.