The French Revolution was a period of political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789, and ended with the coup of 18 Brumaire in November 1799 and the formation of the French Consulate. Many of its ideas are considered fundamental principles of liberal democracy, while its values and institutions remain central to modern French political discourse.

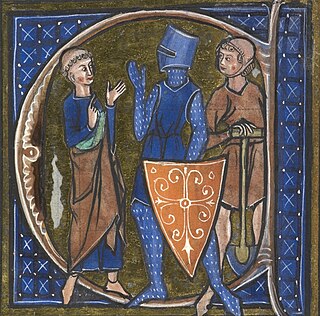

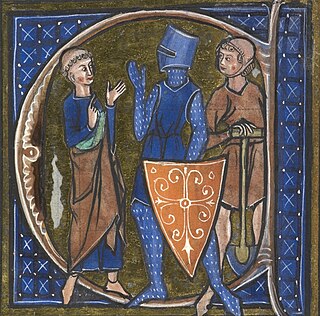

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structuring society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour.

Manorialism, also known as seigneurialism, the manor system or manorial system, was the method of land ownership in parts of Europe, notably France and later England, during the Middle Ages. Its defining features included a large, sometimes fortified manor house in which the lord of the manor and his dependants lived and administered a rural estate, and a population of labourers who worked the surrounding land to support themselves and the lord. These labourers fulfilled their obligations with labour time or in-kind produce at first, and later by cash payment as commercial activity increased. Manorialism was part of the feudal system.

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed during the Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages in Europe and lasted in some countries until the mid-19th century.

The National Convention was the constituent assembly of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for its first three years during the French Revolution, following the two-year National Constituent Assembly and the one-year Legislative Assembly. Created after the great insurrection of 10 August 1792, it was the first French government organized as a republic, abandoning the monarchy altogether. The Convention sat as a single-chamber assembly from 20 September 1792 to 26 October 1795.

The estates of the realm, or three estates, were the broad orders of social hierarchy used in Christendom from the Middle Ages to early modern Europe. Different systems for dividing society members into estates developed and evolved over time.

This glossary of the French Revolution generally does not explicate names of individual people or their political associations; those can be found in List of people associated with the French Revolution.

There is significant disagreement among historians of the French Revolution as to its causes. Usually, they acknowledge the presence of several interlinked factors, but vary in the weight they attribute to each one. These factors include cultural changes, normally associated with the Enlightenment; social change and financial and economic difficulties; and the political actions of the involved parties. For centuries, the French society was divided into three estates or orders.

The Great Fear was a general panic that took place between 22 July to 6 August 1789, at the start of the French Revolution. Rural unrest had been present in France since the worsening grain shortage of the spring. Fuelled by rumours of an aristocrats' "famine plot" to starve or burn out the population, both peasants and townspeople mobilised in many regions.

The Estates General of 1789(French: États Généraux de 1789) was a general assembly representing the French estates of the realm: the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners. It was the last of the Estates General of the Kingdom of France.

The aim of a number of separate policies conducted by various governments of France during the French Revolution ranged from the appropriation by the government of the great landed estates and the large amounts of money held by the Catholic Church to the termination of Christian religious practice and of the religion itself. There has been much scholarly debate over whether the movement was popularly motivated or motivated by a small group of revolutionary radicals. These policies, which ended with the Concordat of 1801, formed the basis of the later and less radical laïcité policies.

Jean-Baptiste de Machault d'Arnouville, comte d'Arnouville, seigneur de Garge et de Gonesse, He was a French statesman, son of Louis Charles Machault d'Arnouville, lieutenant of police.

The French nobility was a privileged social class in France from the Middle Ages until its abolition on 23 June 1790 during the French Revolution.

The ancien régime, now a common metaphor for "a system or mode no longer prevailing", was the political and social system of the Kingdom of France that the French Revolution overturned through its abolition in 1790 of the feudal system of the French nobility and in 1792 through its execution of the king and declaration of a republic.

The Serfdom Patent of 1 November 1781 aimed to abolish aspects of the traditional serfdom system of the Habsburg monarchy through the establishment of basic civil liberties for the serfs.

Serfdom has a long history that dates to ancient times.

Seigneur or lord is an originally feudal title in France before the Revolution, in New France and British North America until 1854, and in the Channel Islands to this day. The seigneur owned a seigneurie, seigneury, or lordship—a form of title or land tenure—as a fief, with its associated obligations and rights over person and property. In this sense, a seigneur could be an individual—male or female, high or low-born—or a collective entity, typically a religious community such as a monastery, seminary, college, or parish. In the wake of the French Revolution, seigneurialism was repealed in France on 4 August 1789 and in the Province of Canada on 18 December 1854. Since then, the feudal title has only been applicable in the Channel Islands and for sovereign princes by their families.

The land reforms done in the Duchy of Savoy, beginning at 1720, was the first land reform that emancipated peasants in France from the bondages of Feudalism.

The Decree on the Abolition of Estates and Civil Ranks was a decree approved by the Central Executive Committee of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies at its meeting on November 23, 1917 and agreed to by the Council of People's Commissars on November 24, 1917. Published on November 25, 1917 in the Newspaper of the Provisional Workers and Peasants Government and Izvestia, on December 21, 1917 published in the Assembly of the Laws and Regulations of the Workers and Peasants Government. The decree contained a provision on the entry into force "from the date of its publication".

From the Middle Ages, the Channel Islands were administered according to a feudal system. Alongside the parishes of Jersey and Guernsey, the fief provided a basic framework for rural life; the system began with the Norman system and largely remained similar to it. Feudalism has retained a more prominent role in the Channel Islands than in the UK. The Channel Islands are remnants of the Duchy of Normandy and are held directly by the crown on a feudal basis as they are self-governing possessions of the British Crown. This peculiarity underscores the deep-seated influence of feudalism in the Channel Islands; their allegiance isn't so much to England but rather directly to the monarch.