You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (January 2023)Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

This article needs additional citations for verification .(May 2015) |

| Constitution of the Year VIII | |

|---|---|

The Constitution of the Year VIII (1799) | |

| Original title | Constitution de l'an VIII |

| Created | 22 Frimaire, Year VIII (13 December 1799) |

| Presented | 24 Frimaire, Year VIII (15 December 1799) |

| Repealed | 16 Thermidor, Year X (4 August 1802) |

| Location | French National Archives |

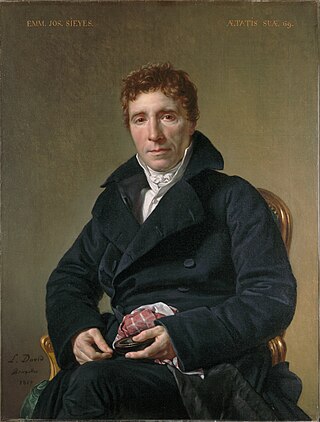

| Author(s) | Initially Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès, later delegated to Daunou |

| Supersedes | Constitution of 5 Fructidor, Year III (Constitution of the Directory) |

The Constitution of the Year VIII (French : Constitution de l'an VIII or French : Constitution du 22 frimaire an VIII) was a national constitution of France, adopted on 24 December 1799 (during Year VIII of the French Republican calendar), which established the form of government known as the Consulate. The coup of 18 Brumaire (9 November 1799) had effectively given all power to Napoleon Bonaparte, and in the eyes of some, ended the French Revolution.

Contents

- Background and Adoption

- New Constitutional Order

- Organs of Executive Power

- Consulate

- Council of State

- Organs of Legislative Power

- Tribunate

- Legislative Body

- Conservative Senate

- Sources

- References

- External links

After the coup, Napoleon and his allies legitimized his position by crafting a Constitution that would be, in the words of Napoleon, "short and obscure". [1] [2] The constitution tailor-made the position of First Consul to give Napoleon most of the powers of a dictator. It was the first constitution since the 1789 Revolution without a Declaration of Rights.

The document vested executive power in three Consuls, but all actual power was held by the First Consul, Bonaparte. This differed from Robespierre's republic of c.1792 to 1795 (which was more radical), and from the oligarchic liberal republic of the Directory (1795–1799). More than anything, the Consulat resembled the autocratic Roman Republic of Caesar Augustus, a conservative republic-in-name, which reminded the French of stability, order, and peace. [3] It has been called a regime of "modern Caesarism". [4] [5] To emphasize this, the authors of the constitutional document used classical Roman terms, such as "Consul", "Senator" and "Tribune".

The Constitution of Year VIII established a legislature of three houses, which was composed of a Conservative Senate of 80 men over the age of 40, a Tribunate of 100 men over the age of 25, and a Legislative Body (Corps législatif) of 300 men over 30 years old.

The Constitution also used the term "notables". The word "notables" had been in common usage under the monarchy. It referred to prominent, "distinguished" men — landholders, merchants, scholars, professionals, clergymen and officials. [6] The people in each district chose a slate of "notables" by popular vote. The First Consul, the Tribunate, and the Corps Législatif each nominated one Senatorial candidate to the rest of the Senate, which chose one candidate from among the three. Once all of its members were picked, it would then appoint the Tribunate, the Corps Législatif, the judges of cassation, and the commissioners of accounts from the National List of notables. [7]

Napoleon held a plebiscite on the Constitution on 7 February 1800. The vote was not binding, but it allowed Napoleon to maintain a veneer of democracy. Lucien Bonaparte announced results of 3,011,007 in favor and 1,562 against the new dispensation. The true result was probably around 1.55 million for it, with several thousand against it. [8]

This Constitution was amended, firstly, by the Constitution of the Year X, which made Napoleon First Consul for Life. A more extensive alteration, the Constitution of the Year XII, established the Bonaparte dynasty with Napoleon as a hereditary Emperor. The first, brief Bourbon Restoration of 1814 abolished the Napoleonic constitutional system, but the Emperor revived it and at once virtually replaced it with the so-called "Additional Act" of April 1815, promulgated on his return to power. The return of Louis XVIII in July 1815 (following the Hundred Days) saw the definitive abolition of Napoleon's constitutional arrangements. The Napoleonic constitutions were completely replaced by the Bourbon Charter of 1814.