The Seneca ( SEN-ik-ə; are a group of Indigenous Iroquoian-speaking people who historically lived south of Lake Ontario, one of the five Great Lakes in North America. Their nation was the farthest to the west within the Six Nations or Iroquois League in New York before the American Revolution. For this reason, they are called “The Keepers of the Western Door.”

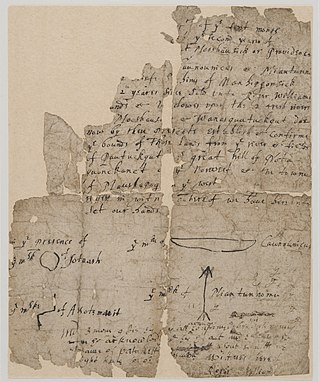

The Phelps and Gorham Purchase was the sale, in 1788, of a portion of a large tract of land in western New York State owned by the Seneca nation of the Iroquois Confederacy to a syndicate of land developers led by Oliver Phelps and Nathaniel Gorham. The larger tract of land is generally known as the "Genesee tract" and roughly encompasses all that portion of New York State west of Seneca Lake, consisting of about 6,000,000 acres (24,000 km2).

The Oneida people are a Native American tribe and First Nations band. They are one of the five founding nations of the Iroquois Confederacy in the area of upstate New York, particularly near the Great Lakes.

The Nonintercourse Act is the collective name given to six statutes passed by the United States Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834 to set boundaries of Native American reservations. The various acts were also intended to regulate commerce between settlers and the natives. The most notable provisions of the act regulate the inalienability of aboriginal title in the United States, a continuing source of litigation for almost 200 years. The prohibition on purchases of Indian lands without the approval of the federal government has its origins in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783.

There are four treaties of Buffalo Creek, named for the Buffalo River in New York. The Second Treaty of Buffalo Creek, also known as the Treaty with the New York Indians, 1838, was signed on January 15, 1838 between the Seneca Nation, Mohawk nation, Cayuga nation, Oneida Indian Nation, Onondaga (tribe), Tuscarora (tribe) and the United States. It covered land sales of tribal reservations under the U.S. Indian Removal program, by which they planned to move most eastern tribes to Kansas Territory west of the Mississippi River.

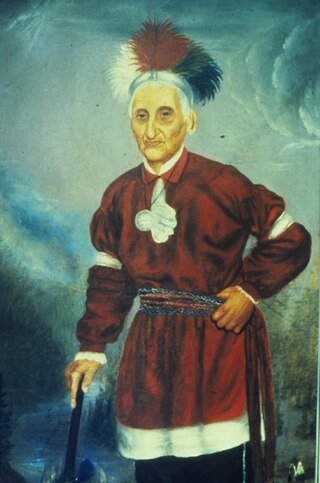

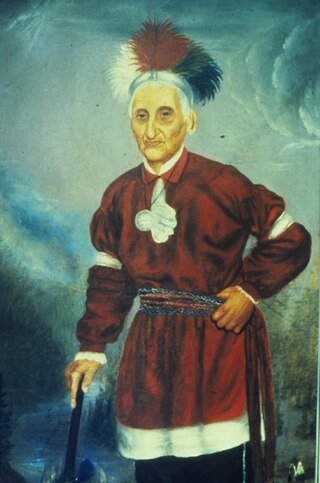

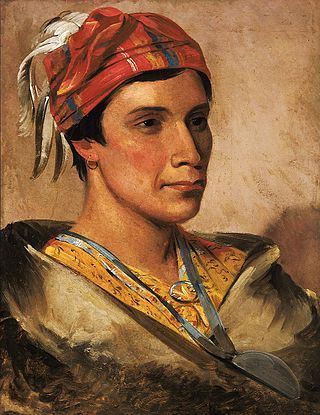

Tah-won-ne-ahs or Thaonawyuthe, known in English as either Chainbreaker to his own people or Governor Blacksnake to the European settlers, was a Seneca war chief and sachem. Along with other Iroquois war chiefs, he led warriors to fight on the side of the British during the American Revolutionary War from 1777 to 1783. He was prominent for his role at the Battle of Oriskany, in which the Loyalist and allied forces ambushed a force of Patriots. After the war, he supported his maternal uncle, Handsome Lake, as a prominent religious leader. Chainbreaker allied with the United States in the War of 1812 and later encouraged some accommodation to European-American settlers, allowing missionaries and teachers on the Seneca reservation.

The Oneida Nation is a federally recognized tribe of Oneida people in Wisconsin. The tribe's reservation spans parts of two counties west of the Green Bay metropolitan area. The reservation was established by treaty in 1838, and was allotted to individual New York Oneida tribal members as part of an agreement with the U.S. government. The land was individually owned until the tribe was formed under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934.

Federal Power Commission v. Tuscarora Indian Nation, 362 U.S. 99 (1960), was a case decided by the United States Supreme Court that determined that the Federal Power Commission was authorized to take lands owned by the Tuscarora Indian tribe by eminent domain under the Federal Power Act for a hydroelectric power project, upon payment of just compensation.

City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York, 544 U.S. 197 (2005), was a Supreme Court of the United States case in which the Court held that repurchase of traditional tribal lands 200 years later did not restore tribal sovereignty to that land. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote the majority opinion.

The United States was the first jurisdiction to acknowledge the common law doctrine of aboriginal title. Native American tribes and nations establish aboriginal title by actual, continuous, and exclusive use and occupancy for a "long time." Individuals may also establish aboriginal title, if their ancestors held title as individuals. Unlike other jurisdictions, the content of aboriginal title is not limited to historical or traditional land uses. Aboriginal title may not be alienated, except to the federal government or with the approval of Congress. Aboriginal title is distinct from the lands Native Americans own in fee simple and occupy under federal trust.

Oneida Indian Nation of New York v. County of Oneida, 414 U.S. 661 (1974), is a landmark decision by the United States Supreme Court concerning aboriginal title in the United States. The original suit in this matter was the first modern-day Native American land claim litigated in the federal court system rather than before the Indian Claims Commission. It was also the first to go to final judgement.

County of Oneida v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York State, 470 U.S. 226 (1985), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case concerning aboriginal title in the United States. The case, sometimes referred to as Oneida II, was "the first Indian land claim case won on the basis of the Nonintercourse Act."

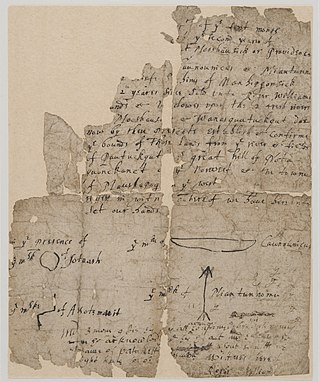

Seneca Nation of Indians v. Christy, 162 U.S. 283 (1896), was the first litigation of aboriginal title in the United States by a tribal plaintiff in the Supreme Court of the United States since Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831). It was the first such litigation by an indigenous plaintiff since Fellows v. Blacksmith (1857) and its companion case of New York ex rel. Cutler v. Dibble (1858). The New York courts held that the 1788 Phelps and Gorham Purchase did not violate the Nonintercourse Act, one of the provisions of which prohibits purchases of Indian lands without the approval of the federal government, and that the Seneca Nation of New York was barred by the state statute of limitations from challenging the transfer of title. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the merits of lower court ruling because of the adequate and independent state grounds doctrine.

Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783 was a proclamation by the Congress of the Confederation dated September 22, 1783 prohibiting the extinguishment of aboriginal title in the United States without the consent of the federal government. The policy underlying the proclamation was inaugurated by the Proclamation of 1763, and continued after the ratification of the United States Constitution by the Nonintercourse Acts of 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1833.

Fellows v. Blacksmith, 60 U.S. 366 (1857), is a United States Supreme Court decision involving Native American law. John Blacksmith, a Tonawanda Seneca, sued agents of the Ogden Land Company for common law claims of trespass, assault, and battery after he was forcibly evicted from his sawmill by the Company's agents. The Court affirmed a judgement in Blacksmith's favor, notwithstanding the fact that the Seneca had executed an Indian removal treaty and the Company held the exclusive right to purchase to the land by virtue of an interstate compact ratified by Congress.

Laura Cornelius Kellogg ("Minnie") ("Wynnogene"), was an Oneida leader, author, orator, activist and visionary. Kellogg, a descendant of distinguished Oneida leaders, was a founder of the Society of American Indians. Kellogg was an advocate for the renaissance and sovereignty of the Six Nations of the Iroquois, and fought for communal tribal lands, tribal autonomy and self-government. Popularly known as "Indian Princess Wynnogene," Kellogg was the voice of the Oneidas and Haudenosaunee people in national and international forums. During the 1920s and 1930s, Kellogg and her husband, Orrin J. Kellogg, pursued land claims in New York on behalf of the Six Nations people. Kellogg's "Lolomi Plan" was a Progressive Era alternative to Bureau of Indian Affairs control emphasizing indigenous American self-sufficiency, cooperative labor and organization, and capitalization of labor. According to historian Laurence Hauptman, "Kellogg helped transform the modern Iroquois, not back into their ancient League, but into major actors, activists and litigants in the modern world of the 20th century Indian politics."

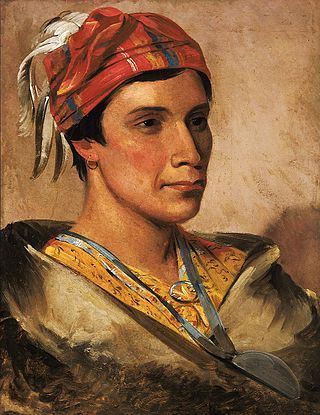

Daniel Bread was an Oneida political and cultural leader who helped the Oneida preserve their culture while adapting to new realities during their transplantation from New York to Wisconsin. He was frequently described as a "principal chief", "head chief", or "sachem" by the Oneida but held no hereditary position and was not an officially condoled chief. Bread was a pragmatist who found ways to compromise between "promoting tribal sovereignty and treaty rights" and cooperating with federal and state officials. He played a major role in adapting the Iroquois condolence ceremony into a July 4 celebration that recognized the alliance of the Oneida with George Washington during the American Revolution. At age 14, Bread was part of the defense of Sackets Harbor during the Battle of Big Sandy Creek.

The Third Treaty of Buffalo Creek or Treaty with the Seneca of 1842 signed by the U.S. and the Seneca Nation modified the Second Treaty of Buffalo Creek. This reflected that the Ogden Company had purchased only two of the four Seneca reservations, the Buffalo Creek and Tonawanda reservations, that the Senecas had agreed to sell in the Second Treaty; it thus restored native title to the Allegany, Cattaraugus and Oil Springs reservations.

The Everett Report of 1922 was a New York State Assembly report compiled by a legislative commission led by Edward A. Everett. It concluded that "the Iroquois were fraudulently dispossessed of over six million acres of land in New York." However, the report was "buried" by New York State and not published until 1971.

Mary Cornelius Winder was a Native American activist who wrote a series of letters to the federal government related to Oneida Indian Nation ancestral land claims.