The Battle of the Nile was a major naval battle fought between the British Royal Navy and the Navy of the French Republic at Aboukir Bay on the Mediterranean coast off the Nile Delta of Egypt from the 1st to the 3rd of August 1798. The battle was the climax of a naval campaign that had raged across the Mediterranean during the previous three months, as a large French convoy sailed from Toulon to Alexandria carrying an expeditionary force under General Napoleon Bonaparte. The British fleet was led in the battle by Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson; they decisively defeated the French under Vice-Admiral François-Paul Brueys d'Aigalliers.

HMS Lion was a 64-gun third-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, of the Worcester class, launched on 3 September 1777 at Portsmouth Dockyard.

Claude-Henri Belgrand de Vaubois was a French general during the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. He is best known for the surrender of Malta to the British in 1800. On 20 August 1808 he was created Comte de Belgrand de Vaubois. Later, his name was inscribed on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris.

The Battle of the Basque Roads, also known as the Battle of Aix Roads, was a major naval battle of the Napoleonic Wars, fought in the narrow Basque Roads at the mouth of the Charente River on the Biscay coast of France. The battle, which lasted from 11–24 April 1809, was unusual in that it pitted a hastily-assembled squadron of small and unorthodox British Royal Navy warships against the main strength of the French Atlantic Fleet. The circumstances were dictated by the cramped, shallow coastal waters in which the battle was fought. The battle is also notorious for its controversial political aftermath in both Britain and France.

Vice-Admiral Sir Henry Blackwood, 1st Baronet, whose memorial is in Killyleagh Parish Church, was an Irish officer of the British Royal Navy.

HMS Foudroyant was an 80-gun third rate of the Royal Navy, one of only two British-built 80-gun ships of the period. Foudroyant was built in the dockyard at Plymouth Dock and launched on 31 March 1798. Foudroyant served Nelson as his flagship from 6 June 1799 until the end of June 1800.

Admiral Granville Leveson Proby, 3rd Earl of Carysfort, known as The Honourable Granville Proby until 1855, was a British naval commander and Whig politician.

HMS Penelope was a fifth-rate frigate of the Royal Navy, launched in 1798 and wrecked in 1815.

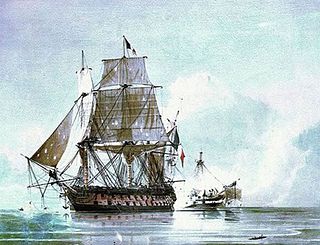

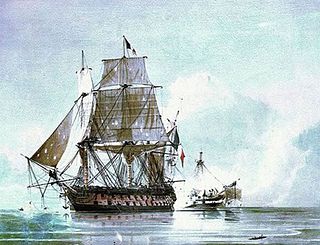

HMS Malta was an 80-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy. She had previously served with the French Navy as the Tonnant-classGuillaume Tell, but was captured in the Mediterranean in 1800 by a British squadron enforcing the blockade of French-occupied Malta. Having served the French for less than four years from her completion in July 1796 to her capture in March 1800, she would eventually serve the British for forty years.

The Mediterranean campaign of 1798 was a series of major naval operations surrounding a French expeditionary force sent to Egypt under Napoleon Bonaparte during the French Revolutionary Wars. The French Republic sought to capture Egypt as the first stage in an effort to threaten British India and support Tipu Sultan, and thus force Great Britain to make peace. Departing Toulon in May 1798 with over 40,000 troops and hundreds of ships, Bonaparte's fleet sailed southeastwards across the Mediterranean Sea. They were followed by a small British squadron under Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson, later reinforced to 13 ships of the line, whose pursuit was hampered by a lack of scouting frigates and reliable information. Bonaparte's first target was the island of Malta, which was under the government of the Knights of St. John and theoretically granted its owner control of the Central Mediterranean. Bonaparte's forces landed on the island and rapidly overwhelmed the defenders, securing the port city of Valletta before continuing to Egypt. When Nelson learned of the French capture of the island, he guessed the French target to be Egypt and sailed for Alexandria, but passed the French during the night of 22 June without discovering them and arrived off Egypt first.

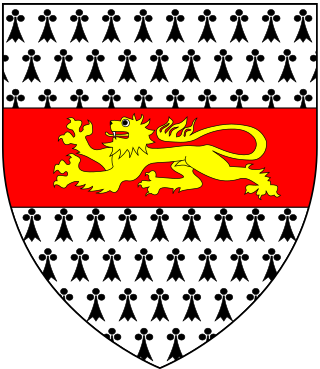

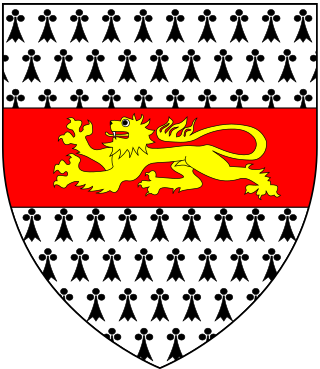

Admiral Sir Manley Dixon, KCB was a prominent Royal Navy officer during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Born into a military family in the late 1750s or early 1760s, Dixon joined the Navy and served as a junior officer in the American Revolutionary War, gaining an independent command in the last year of the war. Promoted to captain seven years later, Dixon then served in the French Revolutionary Wars in the Channel Fleet and off Ireland until 1798, when he gained command of the 64-gun HMS Lion with the Mediterranean Fleet. Employed in the blockade of Cartagena, on 15 July 1798 Lion fought four Spanish frigates and successfully captured one, Santa Dorothea. Transferred to the Siege of Malta later the same year, Dixon remained off the island for two years, capturing the French ship of the line Guillaume Tell at the action of 31 March 1800. After the Peace of Amiens, Dixon remained in various active commands but saw no action and later retired, advancing to a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath and a full admiral.

The action of 18 August 1798 was a minor naval engagement of the French Revolutionary Wars, fought between the British fourth rate ship HMS Leander and the French ship of the line Généreux. Both ships had been engaged at the Battle of the Nile three weeks earlier, in which a British fleet under Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson had destroyed a French fleet at Aboukir Bay on the Mediterranean coast of Egypt. Généreux was one of only four French ships to survive the battle, while Leander had been detached from the British fleet by Nelson on 6 August. On board, Captain Edward Berry sailed as a passenger, charged with carrying despatches to the squadron under Earl St Vincent off Cadiz. On 18 August, while passing the western shore of Crete, Leander was intercepted and attacked by Généreux, which had separated from the rest of the French survivors the day before.

The action of 15 July 1798 was a minor naval battle of the French Revolutionary Wars, fought off the Spanish Mediterranean coast by the Royal Navy ship of the line HMS Lion under Captain Manley Dixon and a squadron of four Spanish Navy frigates under Commodore Don Felix O'Neil. Lion was one of several ships sent into the Western Mediterranean by Vice-Admiral Earl St Vincent, commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet based at the Tagus in Portugal during the late spring of 1798. The Spanish squadron was a raiding force that had sailed from Cartagena in Murcia seven days earlier, and was intercepted while returning to its base after an unsuccessful cruise. Although together the Spanish vessels outweighed the British ship, individually they were weaker and Commodore O'Neil failed to ensure that his manoeuvres were co-ordinated. As a result, one of the frigates, Santa Dorotea, fell out of the line of battle and was attacked by Lion.

The siege of Malta, also known as the siege of Valletta or the French blockade, was a two-year siege and blockade of the French garrison in Valletta and the Three Cities, the largest settlements and main port on the Mediterranean island of Malta, between 1798 and 1800. Malta had been captured by a French expeditionary force during the Mediterranean campaign of 1798, and garrisoned with 3,000 soldiers under the command of Claude-Henri Belgrand de Vaubois. After the British Royal Navy destroyed the French Mediterranean Fleet at the Battle of the Nile on 1 August 1798, the British were able to initiate a blockade of Malta, assisted by an uprising among the native Maltese population against French rule. After its retreat to Valletta, the French garrison faced severe food shortages, exacerbated by the effectiveness of the British blockade. Although small quantities of supplies arrived in early 1799, there was no further traffic until early 1800, by which time starvation and disease were having a disastrous effect on the health, morale, and combat capability of the French troops.

The Battle of the Malta Convoy was a naval engagement of the French Revolutionary Wars fought on 18 February 1800 during the Siege of Malta. The French garrison at the city of Valletta in Malta had been under siege for eighteen months, blockaded on the landward side by a combined force of British, Portuguese and irregular Maltese forces and from the sea by a Royal Navy squadron under the overall command of Lord Nelson from his base at Palermo on Sicily. In February 1800, the Neapolitan government replaced the Portuguese troops with their own forces and the soldiers were convoyed to Malta by Nelson and Lord Keith, arriving on 17 February. The French garrison was by early 1800 suffering from severe food shortages, and in a desperate effort to retain the garrison's effectiveness a convoy was arranged at Toulon, carrying food, armaments and reinforcements for Valletta under Contre-amiral Jean-Baptiste Perrée. On 17 February, the French convoy approached Malta from the southeast, hoping to pass along the shoreline and evade the British blockade squadron.

The action of 19 December 1796 was a minor naval engagement of the French Revolutionary Wars, fought in the last stages of the Mediterranean campaign between two British Royal Navy frigates and two Spanish Navy frigates off the coast of Murcia. The British squadron was the last remaining British naval force in the Mediterranean, sent to transport the British garrison of Elba to safety under the command of Commodore Horatio Nelson. The Spanish under Commodore Don Jacobo Stuart were the vanguard of a much larger squadron. One Spanish frigate was captured and another damaged before Spanish reinforcements drove the British off and recaptured the lost ship.

Charles Inglis was an officer of the Royal Navy who saw service during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, rising to the rank of post-captain.

The Croisière de Bruix was the principal naval campaign of the year 1799 during the French Revolutionary Wars. The expedition began in April 1799 when the bulk of the French Atlantic Fleet under Vice-Admiral Étienne Eustache Bruix departed the base at Brest, evading the British Channel Fleet which was blockading the port and tricking the commander Admiral Lord Bridport into believing their true destination was Ireland. Passing southwards, the French fleet narrowly missed joining with an allied Spanish Navy squadron at Ferrol and was prevented by an easterly gale from uniting with the main Spanish fleet at Cádiz before entering the Mediterranean Sea. The Mediterranean was under British control following the destruction of the French Mediterranean Fleet at the Battle of the Nile in August 1798, and a British fleet nominally under Admiral Earl St Vincent was stationed there. Due however to St. Vincent's ill-health, operational control rested with Vice-Admiral Lord Keith. As Keith sought to chase down the French, the Spanish fleet followed Bruix into the Mediterranean before being badly damaged in a gale and sheltering in Cartagena.

HMS Vincejo, was the Spanish naval brig Vencejo, which was built c.1797, probably at Port Mahon, and that the British captured in 1799. The Royal Navy took her into service and she served in the Mediterranean where she captured a privateer and a French naval brig during the French Revolutionary Wars. After the start of the Napoleonic Wars, the French captured Vencejo in Quiberon Bay in 1804. The French Navy took her into service as Victorine, but then sold her in January 1805. She then served as the French privateer Comte de Regnaud until the British recaptured her in 1810. The Royal Navy did not take her back into service.

Nossa Senhora da Conceição was launched at Lisbon on 13 July 1771 for the Portuguese Navy as a first rate ship of the line of 90 guns. In 1793 she was the flagship of the squadron that the Portuguese Navy provided to assist the British Royal Navy's Channel Fleet. The next year the Portuguese government refitted her and changed her name to Príncipe Real. In 1798-1800 Príncipe Real served in the Mediterranean as the flagship of the Portuguese squadron assisting Admiral Nelson.