Sierra Leone first became inhabited by indigenous African peoples at least 2,500 years ago. The Limba were the first tribe known to inhabit Sierra Leone. The dense tropical rainforest partially isolated the region from other West African cultures, and it became a refuge for peoples escaping violence and jihads. Sierra Leone was named by Portuguese explorer Pedro de Sintra, who mapped the region in 1462. The Freetown estuary provided a good natural harbour for ships to shelter and replenish drinking water, and gained more international attention as coastal and trans-Atlantic trade supplanted trans-Saharan trade.

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the repatriation of freeborn people of color and emancipated slaves to the continent of Africa. It was modeled on an earlier British colonization in Africa, which had sought to resettle London's "black poor".

Sherbro Island is in the Atlantic Ocean, and is included within Bonthe District, Southern Province, Sierra Leone. The island is separated from the African mainland by the Sherbro River in the north and Sherbro Strait in the east. It is 32 miles (51 km) long and up to 15 miles (24 km) wide, covering an area of approximately 230 square miles (600 km2). The western extremity is Cape St. Ann. Bonthe, on the eastern end, is the chief port and commercial centre.

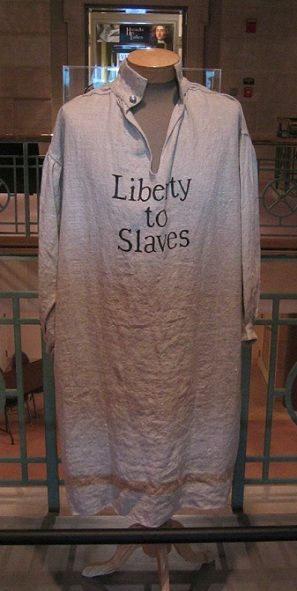

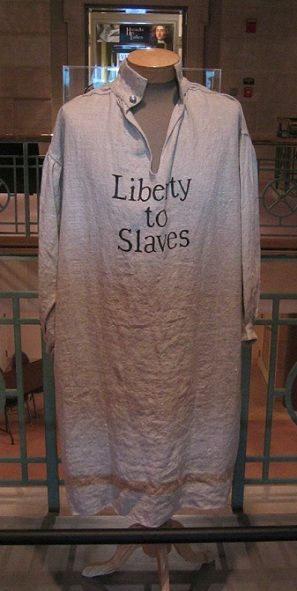

Black Loyalists were African-Americans who sided with the Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War. In particular, the term refers to men who escaped enslavement by Patriot masters and served on the Loyalist side because of the Crown's guarantee of freedom.

The Temne, also called Atemne, Témené, Temné, Téminè, Temeni, Thaimne, Themne, Thimni, Timené, Timné, Timmani, or Timni, are a West African ethnic group, They are predominantly found in the Northern Province of Sierra Leone. Some Temne are also found in Guinea. The Temne constitute the largest ethnic group in Sierra Leone, at 35.5% of the total population, which is slightly bigger than the Mende people at 31.2%. They speak Temne, a Mel branch of the Niger–Congo languages.

The back-to-Africa movement was a political movement in the 19th and 20th centuries advocating for a return of the descendants of African American slaves to the African continent. The movement originated from a widespread belief among some European Americans in the 18th and 19th century United States that African Americans would want to return to the continent of Africa. In general, the political movement was an overwhelming failure; very few former slaves wanted to move to Africa. The small number of freed slaves who did settle in Africa—some under duress—initially faced brutal conditions, due to diseases to which they no longer had biological resistance. As the failure became known in the United States in the 1820s, it spawned and energized the radical abolitionist movement. In the 20th century, the Jamaican political activist and black nationalist Marcus Garvey, members of the Rastafari movement, and other African Americans supported the concept, but few actually left the United States.

Thomas Peters, born Thomas Potters, was a veteran of the Black Pioneers, fighting for the British in the American Revolutionary War. A Black Loyalist, he was resettled in Nova Scotia, where he became a politician and one of the "Founding Fathers" of the nation of Sierra Leone in West Africa. Peters was among a group of influential Black Canadians who pressed the Crown to fulfill its commitment for land grants in Nova Scotia. Later they recruited African-American settlers in Nova Scotia for the colonisation of Sierra Leone in the late eighteenth century.

Lieutenant John Clarkson was a Royal Navy officer and abolitionist, the younger brother of Thomas Clarkson, one of the central figures in the abolition of slavery in England and the British Empire at the close of the 18th century. As agent for the Sierra Leone Company, Lieutenant Clarkson was instrumental in the founding of Freetown, today Sierra Leone's capital city, as a haven for chiefly formerly enslaved African-Americans first relocated to Nova Scotia by the British military authorities following the American Revolutionary War.

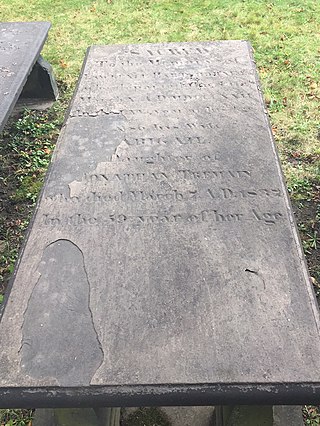

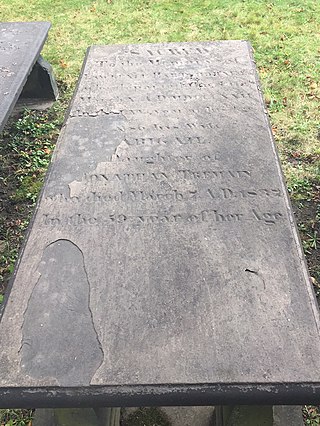

David George was an African-American Baptist preacher and a Black Loyalist from the American South who escaped to British lines in Savannah, Georgia; later he accepted transport to Nova Scotia and land there. He eventually resettled in Freetown, Sierra Leone where he would eventually die. With other enslaved people, George founded the Silver Bluff Baptist Church in South Carolina in 1775, the first black congregation in the present-day United States. He was later affiliated with the First African Baptist Church of Savannah, Georgia. After migration, he founded Baptist congregations in Nova Scotia and Freetown, Sierra Leone. George wrote an account of his life, an important early slave narratives.

Boston King was a former American slave and Black Loyalist, who gained freedom from the British and settled in Nova Scotia after the American Revolutionary War. He later immigrated to Sierra Leone, where he helped found Freetown and became the first Methodist missionary to African indigenous people.

Harry Washington was a Black Loyalist in the American Revolutionary War, and enslaved by Virginia planter George Washington, later the first President of the United States. When the war was lost the British then evacuated him to Nova Scotia. In 1792 he joined nearly 1,200 freedmen for resettlement in Sierra Leone, where they set up a colony of free people of color.

The Book of Negroes is a document created by Brigadier General Samuel Birch, under the direction of Sir Guy Carleton, that records names and descriptions of 3,000 Black Loyalists, enslaved Africans who escaped to the British lines during the American Revolution and were evacuated to points in Nova Scotia as free people of colour.

Daniel Coker (1780–1846), born Isaac Wright, was an African American of mixed race from Baltimore, Maryland. Born a slave, after he gained his freedom, he became a Methodist minister in 1802. He wrote one of the few pamphlets published in the South that protested against slavery and supported abolition. In 1816, he helped found the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first independent black denomination in the United States, at its first national convention in Philadelphia.

Moses "Daddy Moses" Wilkinson or "Old Moses" was an American Wesleyan Methodist preacher and Black Loyalist. His ministry combined Old Testament divination with African religious traditions such as conjuring and sorcery. He gained freedom from slavery in Virginia during the American Revolutionary War and was a Wesleyan Methodist preacher in New York and Nova Scotia. In 1791, he migrated to Sierra Leone, preaching alongside ministers Boston King and Henry Beverhout. There, he established the first Methodist church in Settler Town and survived a rebellion in 1800.

The Nova Scotian Settlers, or Sierra Leone Settlers, were African Americans who founded the settlement of Freetown, Sierra Leone and the Colony of Sierra Leone, on March 11, 1792. The majority of these black American immigrants were among 3,000 African Americans, mostly former slaves, who had sought freedom and refuge with the British during the American Revolutionary War, leaving rebel masters. They became known as the Black Loyalists. The Nova Scotian Settlers were jointly led by African American Thomas Peters, a former soldier, and English abolitionist John Clarkson. For most of the 19th century, the Settlers resided in Settler Town and remained a distinct ethnic group within the Freetown territory, tending to marry among themselves and with Europeans in the colony.

John Kizell was an American immigrant who became a leader in Sierra Leone as it was being developed as a new British colony in the early nineteenth century. Believed born on Sherbro Island, he was kidnapped and enslaved as a child and shipped to Charleston, South Carolina, where he was sold again. Years later, after the American Revolutionary War, during which he gained freedom with the British and was evacuated to Nova Scotia, he eventually returned to West Africa. In 1792, he was among 50 native-born Africans among the 1200 predominantly African-American Black Loyalists resettled in Freetown.

The history of African-American settlement in Africa extends to the beginnings of ex-slave repatriation to Africa from European colonies in the Americas.

Black nationalism is a nationalist movement which seeks liberation, equality, representation and/or self-determination for black people as a distinct national identity, especially in racialized, colonial and postcolonial societies. Its earliest proponents saw it as a way to advocate for democratic representation in culturally plural societies or to establish self-governing independent nation-states for black people. Modern black nationalism often aims for the social, political, and economic empowerment of black communities within white majority societies, either as an alternative to assimilation or as a way to ensure greater representation and equality within predominantly Eurocentric or white cultures.

The Sierra Leone Creole people are an ethnic group of Sierra Leone. The Sierra Leone Creole people are descendants of freed African-American, Afro-Caribbean, and Liberated African slaves who settled in the Western Area of Sierra Leone between 1787 and about 1885. The colony was established by the British, supported by abolitionists, under the Sierra Leone Company as a place for freedmen. The settlers called their new settlement Freetown. Today, the Sierra Leone Creoles are 1.2 percent of the population of Sierra Leone.

The Colony and Protectorate of Sierra Leone was the British colonial administration in Sierra Leone from 1808 to 1961, part of the British Empire from the abolitionism era until the decolonisation era. The Crown colony, which included the area surrounding Freetown, was established in 1808. The protectorate was established in 1896 and included the interior of what is today known as Sierra Leone.