Chinese mythology is mythology that has been passed down in oral form or recorded in literature throughout the area now known as Greater China. Chinese mythology includes many varied myths from regional and cultural traditions. Much of the mythology involves exciting stories full of fantastic people and beings, the use of magical powers, often taking place in an exotic mythological place or time. Like many mythologies, Chinese mythology has in the past been believed to be, at least in part, a factual recording of history. Along with Chinese folklore, Chinese mythology forms an important part of Chinese folk religion and Taoism, especially older popular forms of it. Many stories regarding characters and events of the distant past have a double tradition: ones which present a more historicized or euhemerized version and ones which present a more mythological version.

Shennong (神農), variously translated as "Divine Farmer" or "Divine Husbandman", born Jiang Shinian (姜石年), was a mythological Chinese ruler known as the first Yan Emperor who has become a deity in Chinese folk religion. He is venerated as a culture hero in China.

Suiren appears in Chinese mythology and some works which draw upon it. He is credited as a culture hero who introduced humans to the production of fire and its use for cooking. He was included on some ancient lists of the legendary Three August Ones, who lived long before Emperor Yao, Emperor Shun, and the Xia rulers of the earliest historical Chinese dynasty, even before the Yellow Emperor and Yandi. Suiren’s innovation by tradition has been using the wooden fire drill to create fire. Tradition holds that he ruled over China for 110 years.

The Five Grains or Cereals are a grouping of five farmed crops that were all important in ancient China. Sometimes the crops themselves were regarded as sacred; other times, their cultivation was regarded as a sacred boon from a mythological or supernatural source. More generally, wǔgǔ can be employed in Chinese as a synecdoche referring to all grains or staple crops of which the end produce is of a granular nature. The identity of the five grains has varied over time, with different authors identifying different grains or even categories of grains.

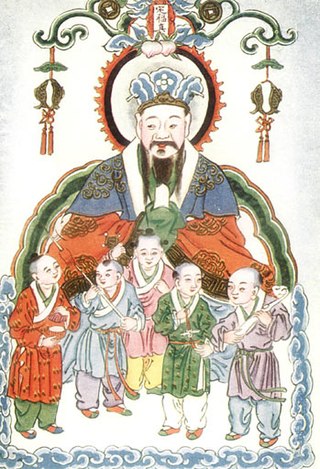

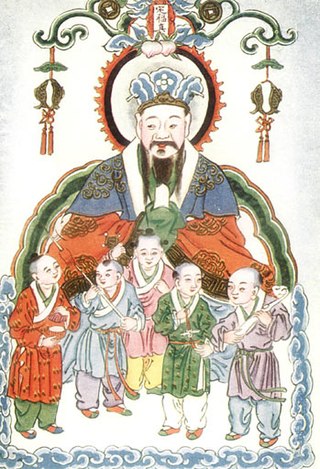

Hòutǔ or Hòutǔshén, also Hòutǔ Niángniáng, otherwise called Dimǔ or Dimǔ Niángniáng, is the deity of all land and earth in Chinese religion and mythology. Houtu is the overlord of all the Tudigongs, Sheji, Shan Shen, City Gods, and landlord gods world wide.

Hou Ji was a legendary Chinese culture hero credited with introducing millet to humanity during the time of the Xia dynasty. Millet was the original staple grain of northern China, prior to the introduction of wheat. His name translates as Lord of Millet and was a title granted to him by Emperor Shun, according to Records of the Grand Historian. Houji was credited with developing the philosophy of Agriculturalism and with service during the Great Flood in the reign of Yao; he was also claimed as an ancestor of the Ji clan that became the ruling family of the Zhou dynasty or a founder of the Zhou.

The Great Flood of Gun-Yu, also known as the Gun-Yu myth, was a major flood in ancient China that allegedly continued for at least two generations, which resulted in great population displacements among other disasters, such as storms and famine. People left their homes to live on the high hills and mountains, or nest on the trees. According to mythological and historical sources, it is traditionally dated to the third millennium BCE, or about 2300-2200 BCE, during the reign of Emperor Yao.

Yi was a tribal leader of Longshan culture and a culture hero in Chinese mythology who helped Shun and Yu the Great control the Great Flood; he served afterwards as a government minister and a successor as ruler of the empire. Yi is also credited with the invention of digging wells. He is the ancestor of royal family of Zhao, Qin, Xu and Liang.

Shujun is a Chinese god of farming and cultivation, also known as Yijun and Shangjun. Alternatively he is a legendary culture hero of ancient times, who was in the family tree of ancient Chinese emperors descended from the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi). According to the various sources, Shujun was the son of Di Jun or else Houji's son or nephew. Shujun is one of the individuals named in Chinese mythology as helping to found the practice of agriculture in China, along with Houji, Di Jun, Shennong, and others. Shujun is specially credited with inventing the use of a draft animal of the bovine family to pull a plow to turn the soil prior to planting.

Di Jun also known as Emperor Jun is one of the ancient supreme deities of China, now known primarily through five chapters of the Shanhaijing. Di Jun had two wives, or consorts: Xihe and Changxi, and Di Jun figures in several stories from Chinese mythology. One of the famous myths in which Di Jun appears is that of the archer Houyi, to whom he gave a bow and arrows. Di Jun is also associated with the agricultural arts, either directly or as the progenitor of other innovators of farming practice, including especially his son, Houji, the Zhou ancestor. Some scholars identify Di Jun and Di Ku as variations from a shared original source.

Xirang, also known as hsi-jang, Swelling Earth, self-renewing soil, breathing earth, and living earth is a magical substance in Chinese mythology that had a self-expanding ability to continuously grow – which made it particularly effective for use by Gun and Yu the Great in fighting the rising waters of the Great Flood.

Four Mountains or Four Peaks variously interpreted from Chinese mythology or the most ancient level of Chinese history as being a person or four persons or four gods, depending upon the specific source. The ambiguous Four Mountains feature prominently in the myth of the Great Flood, and the related myths of Emperor Yao, Gun, Shun, and Yu the Great.

Feather Mountain is one of many important mythological mountains in Chinese mythology, particularly associated with the Great Flood. According to the mythological studies of Lihui Yang, Gun was executed on the "outskirts" of Feather Mountain by Zhu Rong, either for stealing the xirang or for failing to control the flood waters. According to K. C. Wu, Emperor Shun exiled Gun to Feather Mountain for lèse-majesté, but that Gun was not executed; and, rather, that such accounts result from misunderstanding the meanings associated with the ancient Chinese character jí (殛), which appears in certain source works.

Youdu in Chinese mythology is the capital of Hell, or Diyu. Among the various other geographic features believed of Diyu, the capital city has been thought to be named Youdu. It is generally conceived as being similar to a typical Chinese capital city, such as Chang'an, but surrounded with and pervaded with darkness.

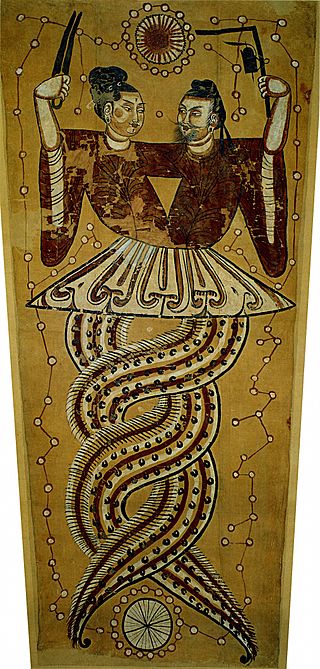

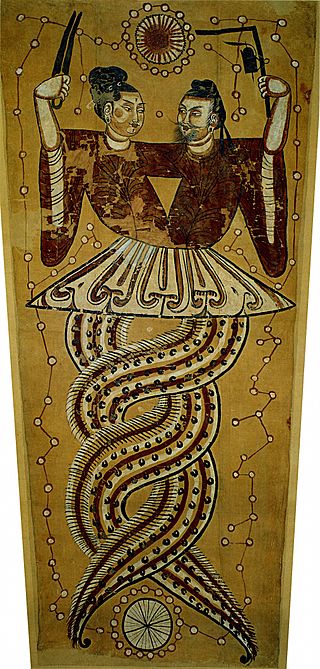

Snakes are an important motif in Chinese mythology. There are various myths, legends, and folk tales about snakes. Chinese mythology refers to these and other myths found in the historical geographic area(s) of China. These myths include Chinese and other languages, as transmitted by Han Chinese as well as other ethnic groups.

Oxen, cows, beef cattle, buffalo and so on are an important motif in Chinese mythology. There are many myths about the oxen or ox-like beings, including both celestial and earthly varieties. The myths range from ones which include oxen or composite beings with ox characteristics as major actors to ones which focus on human or divine actors, in which the role of the oxen are more subsidiary. In some cases, Chinese myths focus on oxen-related subjects, such as plowing and agriculture or ox-powered carriage. Another important role for beef cattle is in the religious capacity of sacrificial offerings.

The Yellow River Map, Scheme, or Diagram, also known by its Chinese name as the Hetu, is an ancient Chinese diagram that appears in myths concerning the invention of writing by Cangjie and other culture heroes. It is usually paired with the Luoshu Square—named in reference to the Yellow River's Luo tributary—and used with the Luoshu in various contexts involving Chinese geomancy, numerology, philosophy, and early natural science.

Chinese mythological geography refers to the related mythological concepts of geography and cosmology, in the context of the geographic area now known as "China", which was typically conceived of as the center of the universe. The "Middle Kingdom" thus served as a reference point for a geography sometimes real and sometimes mythological, including lands and seas surrounding the Middle Land, with mountain peaks and sky above, with sacred grottoes and an underworld below, and even sometimes with some very abstract other worlds.