Related Research Articles

Dyula is a language of the Mande language family spoken mainly in Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast and Mali, and also in some other countries, including Ghana, Guinea and Guinea-Bissau. It is one of the Manding languages and is most closely related to Bambara, being mutually intelligible with Bambara as well as Malinke. It is a trade language in West Africa and is spoken by millions of people, either as a first or second language. Similar to the other Mande languages, it uses tones. It may be written in the Latin, Arabic or N'Ko scripts.

Hausa is a Chadic language that is spoken by the Hausa people in the northern parts of Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon, Benin and Togo, and the southern parts of Niger, Chad and Sudan, with significant minorities in Ivory Coast.

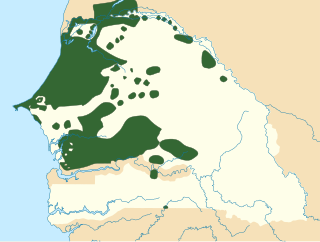

Wolof is a Niger–Congo language spoken by the Wolof people in much of West African subregion of Senegambia that is split between the countries of Senegal, Mauritania, and the Gambia. Like the neighbouring languages Serer and Fula, it belongs to the Senegambian branch of the Niger–Congo language family. Unlike most other languages of its family, Wolof is not a tonal language.

Yoruba is a language spoken in West Africa, primarily in Southwestern and Central Nigeria. It is spoken by the ethnic Yoruba people. The number of Yoruba speakers is roughly 44 million, plus about 2 million second-language speakers. As a pluricentric language, it is primarily spoken in a dialectal area spanning Nigeria, Benin, and Togo with smaller migrated communities in Côte d'Ivoire, Sierra Leone and The Gambia.

N'Ko is an alphabetic script devised by Solomana Kanté in 1949, as a modern writing system for the Manding languages of West Africa. The term N'Ko, which means I say in all Manding languages, is also used for the Manding literary standard written in the N'Ko script.

The Manding languages are a dialect continuum within the Mande language family spoken in West Africa. Varieties of Manding are generally considered to be mutually intelligible – dependent on exposure or familiarity with dialects between speakers – and spoken by 40 million people in the countries Burkina Faso, Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Liberia, Ivory Coast and the Gambia. Their best-known members are Mandinka or Mandingo, the principal language of The Gambia; Bambara, the most widely spoken language in Mali; Maninka or Malinké, a major language of Guinea and Mali; and Jula, a trade language of Ivory Coast and western Burkina Faso. Manding is part of the larger Mandé family of languages.

Ajam is an Arabic word meaning mute. It generally refers to someone whose mother tongue is not Arabic, as well as non-Arabs. During the Arab conquest of Persia, the term became a racial pejorative. In many languages, including Persian, Turkish, Urdu–Hindi, Azerbaijani, Bengali, Kurdish, Gujarati, Malay, Punjabi, and Swahili, Ajam and Ajami refer to Iran and Iranians respectively.

Aljamiado or Aljamía texts are manuscripts that use the Arabic script for transcribing European languages, especially Romance languages such as Old Spanish or Aragonese.

Maore Comorian, or Shimaore, is one of the two indigenous languages spoken in the French-ruled Comorian islands of Mayotte; Shimaore being a dialect of the Comorian language, while ShiBushi is an unrelated Malayo-Polynesian language originally from Madagascar. Historically, Shimaore- and ShiBushi-speaking villages on Mayotte have been clearly identified, but Shimaore tends to be the de facto indigenous lingua franca in everyday life, because of the larger Shimaore-speaking population. Only Shimaore is represented on the local television news program by Mayotte La Première. The 2002 census references 80,140 speakers of Shimaore in Mayotte itself, to which one would have to add people living outside the island, mostly in metropolitan France. There are also 20,000 speakers of Comorian in Madagascar, of which 3,000 are Shimaore speakers.

The Mandinka language, or Mandingo, is a Mande language spoken by the Mandinka people of Guinea, northern Guinea-Bissau, the Casamance region of Senegal, and in The Gambia where it is one of the principal languages.

Fula, also known as Fulani or Fulah, is a Senegambian language spoken by around 36.8 million people as a set of various dialects in a continuum that stretches across some 18 countries in West and Central Africa. Along with other related languages such as Serer and Wolof, it belongs to the Atlantic geographic group within Niger–Congo, and more specifically to the Senegambian branch. Unlike most Niger-Congo languages, Fula does not have tones.

Serer, often broken into differing regional dialects such as Serer-Sine and Serer saloum, is a language of the Senegambian branch of the Niger–Congo family spoken by 1.2 million people in Senegal and 30,000 in the Gambia as of 2009. It is the principal language of the Serer people, and was the language of the early modern kingdoms of Sine, Saloum, and Baol.

The Arabic script is the writing system used for Arabic and several other languages of Asia and Africa. It is the second-most widely used alphabetic writing system in the world, the second-most widely used writing system in the world by number of countries using it, and the third-most by number of users.

The writing systems of Africa refer to the current and historical practice of writing systems on the African continent, both indigenous and those introduced.

Wolofal is a derivation of the Arabic script for writing the Wolof language. It is basically the name of a West African Ajami script as used for that language.

The Fula language is written primarily in the Latin script, but in some areas is still written in an older Arabic script called the Ajami script or in the recently invented Adlam script.

Boko is a Latin-script alphabet used to write the Hausa language. The first boko alphabet was devised by Europeans in the early 19th century, and developed in the early 20th century by the British and French colonial authorities. It was made the official Hausa alphabet in 1930. Since the 1950s boko has been the main alphabet for Hausa. Arabic script (ajami) is now only used in Islamic schools and for Islamic literature. Since the 1980s, Nigerian boko has been based on the Pan-Nigerian alphabet.

A number of writing systems have been used to transcribe the Somali language. Of these, the Somali Latin alphabet is the most widely used. It has been the official writing script in Somalia since the Supreme Revolutionary Council formally introduced it in October 1972, and was disseminated through a nationwide rural literacy campaign. Prior to the twentieth century, the Arabic script was used for writing Somali. An extensive literary and administrative corpus exists in Arabic script. It was the main script historically used by the various Somali sultans to keep records. Writing systems developed locally in the twentieth century include the Osmanya, Borama and Kaddare scripts.

Berber orthography is the writing system(s) used to transcribe the Berber languages.

Swahili Ajami script refers to the alphabet derived from Arabic script that is used for the writing of Swahili language.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ngom, Fallou (2016-08-01). Muslims beyond the Arab World. Oxford University Press. pp. 8–9. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190279868.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-027986-8.

- 1 2 Ngom, Fallou (2018-02-15). Albaugh, Ericka A.; de Luna, Kathryn M. (eds.). "Ajami Literacies of West Africa". Oxford Scholarship Online. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190657543.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-065754-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pasch, Helma (January 2008). "Competing scripts: the introduction of the Roman alphabet in Africa". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2008 (191): 2, 9–10. doi:10.1515/IJSL.2008.025. ISSN 0165-2516. S2CID 144394668.

- ↑ Callahan, Molly (21 December 2022). "Unearthing a Long Ignored African Writing System, One Researcher Finds African History, by Africans". Boston University. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ↑ Donaldson, Coleman (1 October 2013). "Jula Ajami in Burkina Faso: A Grassroots Literacy in the Former Kong Empire". Working Papers in Educational Linguistics (WPEL). 28 (2): 19–36. ISSN 1548-3134.

- ↑ "Saudi Aramco World : From Africa, in Ajami". Archived from the original on 2014-11-30. Retrieved 2011-10-16.