Salmon is the common name for several species of ray-finned fish in the family Salmonidae. Other fish in the same family include trout, char, grayling, and whitefish. Salmon are native to tributaries of the North Atlantic and Pacific Ocean. Many species of salmon have been introduced into non-native environments such as the Great Lakes of North America and Patagonia in South America. Salmon are intensively farmed in many parts of the world.

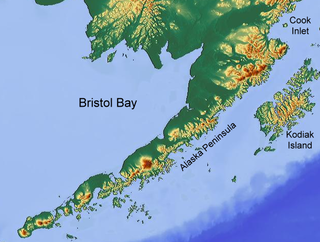

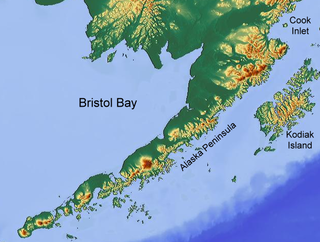

Bristol Bay is the easternmost arm of the Bering Sea, at 57° to 59° North 157° to 162° West in Southwest Alaska. Bristol Bay is 400 km (250 mi) long and 290 km, (180 mi) wide at its mouth. A number of rivers flow into the bay, including the Cinder, Egegik, Igushik, Kvichak, Meshik, Nushagak, Naknek, Togiak, and Ugashik.

Gillnetting is a fishing method that uses gill nets: vertical panels of netting that hang from a line with regularly spaced floaters that hold the line on the surface of the water. The floats are sometimes called "corks" and the line with corks is generally referred to as a "cork line." The line along the bottom of the panels is generally weighted. Traditionally this line has been weighted with lead and may be referred to as "lead line." A gillnet is normally set in a straight line. Gillnets can be characterized by mesh size, as well as colour and type of filament from which they are made. Fish may be caught by gill nets in three ways:

- Wedged – held by the mesh around the body.

- Gilled – held by mesh slipping behind the opercula.

- Tangled – held by teeth, spines, maxillaries, or other protrusions without the body penetrating the mesh.

The chum salmon is a species of anadromous fish in the salmon family. It is a Pacific salmon, and may also be known as dog salmon or keta salmon, and is often marketed under the name silverbrite salmon. The name chum salmon comes from the Chinook Jargon term tzum, meaning "spotted" or "marked", while keta in the scientific name comes from the Evenki language of Eastern Siberia via Russian.

The Chinook salmon is the largest species of Pacific salmon as well as the largest in the genus Oncorhynchus. Its common name is derived from the Chinookan peoples. Other vernacular names for the species include king salmon, Quinnat salmon, spring salmon, chrome hog, and Tyee salmon. The scientific species name is based on the Russian common name chavycha (чавыча).

The sockeye salmon, also called red salmon, kokanee salmon, or blueback salmon, is an anadromous species of salmon found in the Northern Pacific Ocean and rivers discharging into it. This species is a Pacific salmon that is primarily red in hue during spawning. They can grow up to 84 cm in length and weigh 2.3 to 7 kg (5–15 lb). Juveniles remain in freshwater until they are ready to migrate to the ocean, over distances of up to 1,600 km (1,000 mi). Their diet consists primarily of zooplankton. Sockeye salmon are semelparous, dying after they spawn. Some populations, referred to as kokanee, do not migrate to the ocean and live their entire lives in freshwater.

The coho salmon is a species of anadromous fish in the salmon family and one of the five Pacific salmon species. Coho salmon are also known as silver salmon or "silvers". The scientific species name is based on the Russian common name kizhuch (кижуч).

Oncorhynchus is a genus of fish in the family Salmonidae; it contains the Pacific salmon and Pacific trout. The name of the genus is derived from the Greek ὄγκος + ῥύγχος, in reference to the hooked jaws of males in the mating season.

The Baker River is an approximately 30-mile (48 km), southward-flowing tributary of the Skagit River in northwestern Washington in the United States. It drains an area of the high North Cascades in the watershed of Puget Sound north of Seattle, and east of Mount Baker. With a watershed of approximately 270 square miles (700 km2) in a complex of deep valleys partially inside North Cascades National Park, it is the last major tributary of the Skagit before the larger river reaches its mouth on Skagit Bay. The river flows through Concrete, Washington, near its mouth and has two hydroelectric dams owned by Puget Sound Energy.

A fish wheel, also known as a salmon wheel, is a device situated in rivers for catching fish which looks and operates like a watermill. However, in addition to paddles, a fish wheel is outfitted with wire baskets designed to catch and carry fish from the water and into a nearby holding tank. The current of the river presses against the submerged paddles and rotates the wheel, passing the baskets through the water where they intercept fish that are swimming or drifting. Naturally a strong current is most effective in spinning the wheel, so fish wheels are typically situated in shallow rivers with brisk currents, close to rapids, or waterfalls. The baskets are built at an outward-facing slant with an open end so the fish slide out of the opening and into the holding tank where they await collection. Yield is increased if fish swimming upstream are channeled toward the wheel by weirs.

The Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) is a department within the government of Alaska. ADF&G's mission is to protect, maintain, and improve the fish, game, and aquatic plant resources of the state, and manage their use and development in the best interest of the economy and the well-being of the people of the state, consistent with the sustained yield principle. ADF&G manages approximately 750 active fisheries, 26 game management units, and 32 special areas. From resource policy to public education, the department considers public involvement essential to its mission and goals. The department is committed to working with tribes in Alaska and with a diverse group of State and Federal agencies. The department works cooperatively with various universities and nongovernmental organizations in formal and informal partnership arrangements, and assists local research or baseline environmental monitoring through citizen science programs.

This page is a list of fishing topics.

As with other countries, the 200 nautical miles (370 km) exclusive economic zone (EEZ) off the coast of the United States gives its fishing industry special fishing rights. It covers 11.4 million square kilometres, which is the second largest zone in the world, exceeding the land area of the United States.

The aquaculture of salmonids is the farming and harvesting of salmonids under controlled conditions for both commercial and recreational purposes. Salmonids, along with carp, and tilapia are the three most important fish species in aquaculture. The most commonly commercially farmed salmonid is the Atlantic salmon. In the U.S. Chinook salmon and rainbow trout are the most commonly farmed salmonids for recreational and subsistence fishing through the National Fish Hatchery System. In Europe, brown trout are the most commonly reared fish for recreational restocking. Commonly farmed nonsalmonid fish groups include tilapia, catfish, sea bass, and bream.

Aquaculture in Alaska is dominated by the production of shellfish and aquatic plants. These include Pacific oysters, blue mussels, littleneck clams, scallops, and bull kelp. Finfish farming has been prohibited in Alaska by the 16.40.210 Alaskan statute, however non-profit mariculture continues to provide a steady supply of aquaculture in the state. Many organizations that helped the ban, now encourage the growing of shellfish and other oysters.

A salmon cannery is a factory that commercially cans salmon. It is a fish-processing industry that became established on the Pacific coast of North America during the 19th century, and subsequently expanded to other parts of the world that had easy access to salmon.

The Pacific Salmon Commission is a regulatory body run jointly by the Canadian and United States governments. Its mandate is to protect stocks of the five species of Pacific salmon. Its precursor was the International Pacific Salmon Fisheries Commission, which operated from 1937 to 1985. The PSC enforces the Pacific Salmon Treaty, ratified by Canada and the U.S. in 1985.

Salmon population levels are of concern in the Atlantic and in some parts of the Pacific. Salmon are anadromous - they rear and grow in freshwater, migrate to the ocean to reach sexual maturity, and then return to freshwater to spawn. Determining how environmental stressors and climate change will affect these fisheries is challenging due to their lives split between fresh and saltwater. Environmental variables like warming temperatures and habitat loss are detrimental to salmon abundance and survival. Other human influenced effects on salmon like overfishing and gillnets, sea lice from farm raised salmon, and competition from hatchery released salmon have negative effects as well.

The Coast Salish people of the Canadian Pacific coast depend on salmon as a staple food source, as they have done for thousands of years. Salmon has also served as a source of wealth and trade and is deeply embedded in their culture, identity, and existence as First Nations people of Canada. Traditional fishing is deeply tied to Coast Salish culture and salmon were seen "as gift-bearing relatives, and were treated with great respect" since all living things were once people according to traditional Coast Salish beliefs. Salmon are seen by the Coast Salish peoples are beings similar to people but spiritually superior.

The Pacific Salmon War was a period of heightened tensions between Canada and the United States over the Pacific Salmon catch. It began in 1992 after the first Pacific Salmon Treaty, which had been ratified in 1985, expired, and lasted until a new agreement was signed in 1999. Disagreements were high in 1994, when a transit fee was set on American fishing vessels using the Inside Passage and a ferry was blockaded by fishing boats in Friday Harbor, Washington.