Laconia or Lakonia is a historical and administrative region of Greece located on the southeastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. Its administrative capital is Sparta. The word laconic—to speak in a blunt, concise way—is derived from the name of this region, a reference to the ancient Spartans who were renowned for their verbal austerity and blunt, often pithy remarks.

Mehrgarh is a Neolithic archaeological site situated on the Kacchi Plain of Balochistan in Pakistan. It is located near the Bolan Pass, to the west of the Indus River and between the modern-day Pakistani cities of Quetta, Kalat and Sibi. The site was discovered in 1974 by the French Archaeological Mission led by the French archaeologists Jean-François Jarrige and his wife, Catherine Jarrige. Mehrgarh was excavated continuously between 1974 and 1986, and again from 1997 to 2000. Archaeological material has been found in six mounds, and about 32,000 artifacts have been collected from the site. The earliest settlement at Mehrgarh—located in the northeast corner of the 495-acre (2.00 km2) site—was a small farming village dated between 7000 BCE and 5500 BCE.

The Mani Peninsula, also long known by its medieval name Maina or Maïna, is a geographical and cultural region in the Peloponnese of Southern Greece and home to the Maniots, who claim descent from the ancient Spartans. The capital city of Mani is Areopoli. Mani is the central of three peninsulas which extend southwards from the Peloponnese. To the east is the Laconian Gulf, to the west the Messenian Gulf. The Mani peninsula forms a continuation of the Taygetos mountain range, the western spine of the Peloponnese.

Franchthi Cave or Frankhthi Cave is an archaeological site overlooking Kiladha Bay, in the Argolic Gulf, opposite the village of Kiladha in southeastern Argolis, Greece.

Cape Matapan, also named as Cape Tainaron or Taenarum, or Cape Tenaro, is situated at the end of the Mani Peninsula, Greece. Cape Matapan is the southernmost point of mainland Greece, and the second southernmost point in mainland Europe. It separates the Messenian Gulf in the west from the Laconian Gulf in the east.

Pyrgos Dirou is a town in Mani, Laconia, Greece. It is part of the municipal unit of Oitylo of the municipality of East Mani. It is located around 26 km from Areopoli.

The year 1978 in archaeology involved some significant events.

Proto-writing consists of visible marks communicating limited information. Such systems emerged from earlier traditions of symbol systems in the early Neolithic, as early as the 7th millennium BC in China and Southeastern Europe. They used ideographic or early mnemonic symbols or both to represent a limited number of concepts, in contrast to true writing systems, which record the language of the writer.

The Archaeological Museum of Nafplio is a museum in the town of Nafplio of the Argolis region in Greece. It has exhibits of the Neolithic, Chalcolithic, Helladic, Mycenaean, Classical, Hellenistic and Roman periods from all over southern Argolis. The museum is situated in the central square of Nafplion. It is housed in two floors of the old Venetian barracks.

Hajji Firuz Tepe is an archaeological site located in West Azarbaijan Province in north-western Iran and lies in the north-western part of the Zagros Mountains. The site was excavated between 1958 and 1968 by archaeologists from the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. The excavations revealed a Neolithic village that was occupied in the second half of the sixth millennium BC where some of the oldest archaeological evidence of grape-based wine was discovered in the form of organic residue in a pottery jar.

Parc Cwm long cairn, also known as Parc le Breos burial chamber, is a partly restored Neolithic chambered tomb, identified in 1937 as a Severn-Cotswold type of chambered long barrow. The cromlech, a megalithic burial chamber, was built around 5850 years before present (BP), during the early Neolithic. It is about seven 1⁄2 miles (12 km) west south–west of Swansea, Wales, in what is now known as Coed y Parc Cwm at Parc le Breos, on the Gower Peninsula.

Archeological sites in Azerbaijan first gained public interest in the mid-19th century and were reported by European travellers.

Neolithic Greece is an archaeological term used to refer to the Neolithic phase of Greek history beginning with the spread of farming to Greece in 7000–6500 BC. During this period, many developments occurred such as the establishment and expansion of a mixed farming and stock-rearing economy, architectural innovations, as well as elaborate art and tool manufacturing. Neolithic Greece is part of the Prehistory of Southeastern Europe.

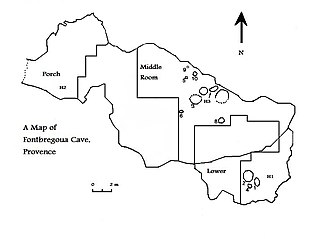

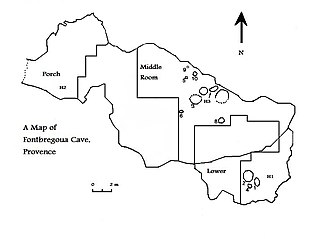

Fontbrégoua Cave is an archaeological site located in Provence, Southeastern France. It was used by humans in the fifth and fourth millennia BCE, in what is now known as the Early and Middle Neolithic. A temporary residential site, it was used by Neolithic agriculturalists as a storage area for their herds of goats and sheep, and also contained a number of bone depositions, containing the remains of domestic species, wild animals, and humans. The inclusion of the latter of these deposits led the archaeological team studying the site to propose that cannibalism had taken place at Fontbrégoua, although other archaeologists have instead suggested that they represent evidence of secondary burial.

The Temple of Poseidon at Tainaron is on the extreme point of the Mani Peninsula, the middle finger of the Peloponnese peninsula. It was dedicated to Poseidon Asphaleios, meaning "Poseidon of Safety".

The Pigi Athinas is an archaeological site at the eastern foot of Mount Olympus, near the village of Platamonas.

The archaeology of Greece includes artificial remains, geographical landscapes, architectural remains, and biofacts. The history of Greece as a country and region is believed to have begun roughly 1–2 million years ago when Homo erectus first colonized Europe. From the first colonization, Greek history follows a sequential pattern of development alike to the rest of Europe. Neolithic, Bronze, Iron and Classical Greece are highlights of the Greek archaeological record, with an array of archaeological finds relevant to these periods.

The Embracing Skeletons of Alepotrypa are a pair of human skeletons dated as approximately 5,800 years old. They were discovered by archaeologists in the Alepotrypa cave in Laconia, Greece, home to a human settlement in the Neolithic age between 6,000 B.C. and 3,200 B.C. The pair were dated to 3,800 B.C. and DNA analysis confirmed that the remains belong to a man and woman who died when they were 20 to 25 years of age.

Abattoir Hill, pronounced in Hebrew as Giv'at Bet Hamitbahayim, is an archaeological site in Tel Aviv, Israel, located near the southern bank of the Yarkon River. The site is a natural hill made of Kurkar, a local type of sandstone. In 1930 ancient burials and tools were discovered upon the construction of an abattoir on top of the hill, hence its name. Between 1950 and 1953, Israeli archaeologist Jacob Kaplan studied the site, ahead of the construction of new residential units and streets on it. He discovered the remains of burials and small settlements spanning from the Chalcolithic period to the Persian period. In 1965 and 1970 Kaplan conducted two more excavations next to the slaughterhouse and discovered settlement remains from the Bronze Age and the Persian period. In February 1992 a salvage excavation was conducted by Yossi Levy after antiquities were damaged by development works. Two burial tombs dated between the Persian period and the Early Arab period were discovered. In June 1998 another salvage excavation was conducted by Kamil Sari after ancient remains were damaged by work of the Electric Corporation. Two kilns were unearthed, similar to two found by Kaplan.

An Son is a mounded archaeological site located in the An Ninh Tay commune of the Đức Hòa district along the Vam Co Dong River in Southern Vietnam. The site was originally discovered in 1938 by Louis Malleret and Paul Levy. Multiple excavations over a period of six decades have revealed that An Son was continuously occupied during the Neolithic period between approximately 2300-1200 B.C. During the excavations, archaeologists found many artifacts indicative of a Neolithic lifestyle similar to other Neolithic sites in Southern Vietnam and Thailand. Excavations have found pottery as well as ceramic productions. Furthermore, the burials found from excavations at An Son have gathered evidence of ritual ceremonies, an indication of the belief system of this area.