Amanita muscaria, commonly known as the fly agaric or fly amanita, is a basidiomycete of the genus Amanita. It is a large white-gilled, white-spotted, and usually red mushroom.

Amanita phalloides, commonly known as the death cap, is a deadly poisonous basidiomycete fungus, one of many in the genus Amanita. Widely distributed across Europe, but introduced to other parts of the world since the late twentieth century, A. phalloides forms ectomycorrhizas with various broadleaved trees. In some cases, the death cap has been introduced to new regions with the cultivation of non-native species of oak, chestnut, and pine. The large fruiting bodies (mushrooms) appear in summer and autumn; the caps are generally greenish in colour with a white stipe and gills. The cap colour is variable, including white forms, and is thus not a reliable identifier.

The name destroying angel applies to several similar, closely related species of deadly all-white mushrooms in the genus Amanita. They are Amanita virosa in Europe and A. bisporigera and A. ocreata in eastern and western North America, respectively. Another European species of Amanita referred to as the destroying angel, Amanita verna - also referred to as the 'Fool's mushroom' - was first described in France in 1780.

The genus Amanita contains about 600 species of agarics, including some of the most toxic known mushrooms found worldwide, as well as some well-regarded edible species. The genus is responsible for approximately 95% of fatalities resulting from mushroom poisoning, with the death cap accounting for about 50% on its own. The most potent toxin present in these mushrooms is α-Amanitin.

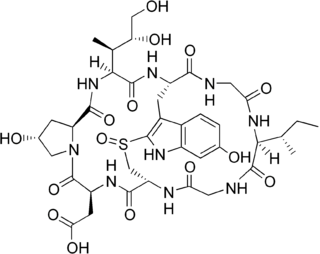

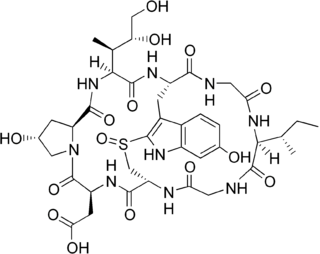

α-Amanitin (alpha-Amanitin) is a cyclic peptide of eight amino acids. It is possibly the most deadly of all the amatoxins, toxins found in several species of the mushroom genus Amanita, one being the death cap as well as the destroying angel, a complex of similar species, principally A. virosa and A. bisporigera. It is also found in the mushrooms Galerina marginata and Conocybe filaris. The oral LD50 of amanitin is 100 μg/kg for rats.

Mushroom poisoning is poisoning resulting from the ingestion of mushrooms that contain toxic substances. Symptoms can vary from slight gastrointestinal discomfort to death in about 10 days. Mushroom toxins are secondary metabolites produced by the fungus.

Amanita virosa, commonly known in Europe as the destroying angel or the European destroying angel amanita, is a deadly poisonous basidiomycete fungus, one of many in the genus Amanita. Occurring in Europe, A. virosa associates with various deciduous and coniferous trees. The large fruiting bodies appear in summer and autumn; the caps, stipes and gills are all white in colour.

Amatoxin is the collective name of a subgroup of at least nine related toxic compounds found in three genera of poisonous mushrooms and one species of the genus Pholiotina. Amatoxins are very potent, as little as half a mushroom cap can cause severe liver injury if swallowed.

Amanita verna, commonly known as the fool's mushroom or the spring destroying angel, is a deadly poisonous basidiomycete fungus, one of many in the genus Amanita. Occurring in Europe in spring, A. verna associates with various deciduous and coniferous trees. The caps, stipes and gills are all white in colour.

Galerina marginata, known colloquially as funeral bell, deadly skullcap, autumn skullcap or deadly galerina, is a species of extremely poisonous mushroom-forming fungus in the family Hymenogastraceae of the order Agaricales. It contains the same deadly amatoxins found in the death cap. Ingestion in toxic amounts causes severe liver damage with vomiting, diarrhea, hypothermia, and eventual death if not treated rapidly. About ten poisonings have been attributed to the species now grouped as G. marginata over the last century.

Amanita velosa, commonly known as the springtime amanita, or bittersweet orange ringless amanita is a species of agaric found in California, as well as southern Oregon and Baja California. Although a prized edible mushroom, it bears similarities to some deadly poisonous species.

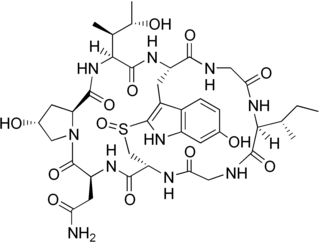

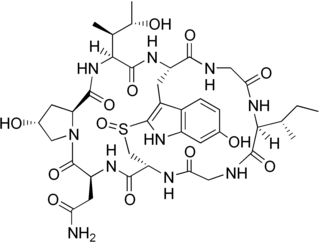

β-Amanitin (beta-Amanitin) is a cyclic peptide comprising eight amino acids. It is part of a group of toxins called amatoxins, which can be found in several mushrooms belonging to the genus Amanita. Some examples are the death cap and members of the destroying angel complex, which includes A. virosa and A. bisporigera. Due to the presence of α-Amanitin, β-Amanitin, γ-Amanitin and epsilon-Amanitin these mushrooms are highly lethal to human beings.

γ-Amanitin (gamma-Amanitin) is a cyclic peptide of eight amino acids. It is an amatoxin, a group of toxins isolated from and found in several members of the mushroom genus Amanita, one being the death cap as well as the destroying angel, a complex of similar species, principally A. virosa and A. bisporigera. The compound is highly toxic, inhibits RNA polymerase II, disrupts synthesis of mRNA, and can be fatal.

The phallotoxins consist of at least seven compounds, all of which are bicyclic heptapeptides, isolated from the death cap mushroom (Amanita phalloides). They differ from the closely related amatoxins by being one residue smaller, both in the final product and the precursor protein.

Galerina sulciceps is a dangerously toxic species of fungus in the family Strophariaceae, of the order Agaricales. It is distributed in tropical Indonesia and India, but has reportedly been found fruiting in European greenhouses on occasion. More toxic than the deathcap, G. sulciceps has been shown to contain the toxins alpha- (α-), beta- (β-) and gamma- (γ-) amanitin; a series of poisonings in Indonesia in the 1930s resulted in 14 deaths from the consumption of this species. It has a typical "little brown mushroom" appearance, with few obvious external characteristics to help distinguish it from many other similar nondescript brown species. The fruit bodies of the fungus are tawny to ochre, deepening to reddish-brown at the base of the stem. The gills are well-separated, and there is no ring present on the stem.

Amanita bisporigera is a deadly poisonous species of fungus in the family Amanitaceae. It is commonly known as the eastern destroying angel amanita, the eastern North American destroying angel or just as the destroying angel, although the fungus shares this latter name with three other lethal white Amanita species, A. ocreata, A. verna and A. virosa. The mushroom has a smooth white cap that can reach up to 10 centimetres across and a stipe up to 14 cm tall with a white skirt-like ring near the top. The bulbous stipe base is covered with a membranous sac-like volva. The white gills are free from attachment to the stalk and crowded closely together. As the species name suggests, A. bisporigera typically bears two spores on the basidia, although this characteristic is not immutable. A. bisporigera closely resembles a few other white amanitas, including the equally deadly A. virosa and A. verna.

Amanita exitialis, also known as the Guangzhou destroying angel, is a mushroom of the large genus Amanita. It is distributed in eastern Asia, and probably also in India where it has been misidentified as A. verna. Deadly poisonous, it is a member of section Phalloideae and related to the death cap A. phalloides. The fruit bodies (mushrooms) are white, small to medium-sized with caps up to 7 cm (2.8 in) in diameter, a somewhat friable ring and a firm volva. Unlike most agaric mushrooms which typically have four-spored basidia, the basidia of A. exitialis are almost entirely two-spored. Eight people were fatally poisoned in China after consuming the mushroom in 2000, and another 20 have been fatally poisoned since that incident. Molecular analysis shows that the species has a close phylogenetic relationship with three other toxic white Amanitas: A. subjunquillea var. alba, A. virosa and A. bisporigera.

Amanita sphaerobulbosa, commonly known as the Asian abrupt-bulbed Lepidella, is a species of agaric fungus in the family Amanitaceae. First described by mycologist Tsuguo Hongo in 1969, it is found in Southern Asia.

Amanita fuliginea, commonly known as the east Asian brown death cap, is a species of deadly poisonous mushroom in the family Amanitaceae. The fruit bodies have convex, dark gray to blackish caps measuring 3–6 cm (1.2–2.4 in) in diameter. The gills, largely free from attachment to the stipe, are white and have short gills (lamellulae) interspersed. The spores are roughly spherical, amyloid, and typically measure 8–11 by 7–9.5 µm. The species was described as new to science by Japanese mycologist Tsuguo Hongo in 1953. A. fuliginea is classified in Amanita section Phalloideae, which contains the infamous destroying angel.

Amanita hygroscopia, also known as the pink-gilled destroying angel is a deadly poisonous fungus, one of many in the genus Amanita.