Felidae is the family of mammals in the order Carnivora colloquially referred to as cats. A member of this family is also called a felid. The term "cat" refers both to felids in general and specifically to the domestic cat.

The jaguar is a large cat species and the only living member of the genus Panthera native to the Americas. With a body length of up to 1.85 m and a weight of up to 158 kg (348 lb), it is the biggest cat species in the Americas and the third largest in the world. Its distinctively marked coat features pale yellow to tan colored fur covered by spots that transition to rosettes on the sides, although a melanistic black coat appears in some individuals. The jaguar's powerful bite allows it to pierce the carapaces of turtles and tortoises, and to employ an unusual killing method: it bites directly through the skull of mammalian prey between the ears to deliver a fatal blow to the brain.

The lion is a large cat of the genus Panthera, native to Africa and India. It has a muscular, broad-chested body; a short, rounded head; round ears; and a hairy tuft at the end of its tail. It is sexually dimorphic; adult male lions are larger than females and have a prominent mane. It is a social species, forming groups called prides. A lion's pride consists of a few adult males, related females, and cubs. Groups of female lions usually hunt together, preying mostly on large ungulates. The lion is an apex and keystone predator; although some lions scavenge when opportunities occur and have been known to hunt humans, lions typically do not actively seek out and prey on humans.

The leopard is one of the five extant species in the genus Panthera. It has a pale yellowish to dark golden fur with dark spots grouped in rosettes. Its body is slender and muscular reaching a length of 92–183 cm (36–72 in) with a 66–102 cm (26–40 in) long tail and a shoulder height of 60–70 cm (24–28 in). Males typically weigh 30.9–72 kg (68–159 lb), and females 20.5–43 kg (45–95 lb).

Panthera is a genus within the family Felidae, it is one of two extant genera in the subfamily Pantherinae, and contains the largest living members of the cat family. There are 5 living species, the tiger, jaguar, lion, leopard and snow leopard and a number of extinct species.

Smilodon is a genus of felids belonging to the extinct subfamily Machairodontinae. It is one of the best known saber-toothed predators and prehistoric mammals. Although commonly known as the saber-toothed tiger, it was not closely related to the tiger or other modern cats. Smilodon lived in the Americas during the Pleistocene epoch. The genus was named in 1842 based on fossils from Brazil; the generic name means "scalpel" or "two-edged knife" combined with "tooth". Three species are recognized today: S. gracilis, S. fatalis, and S. populator. The two latter species were probably descended from S. gracilis, which itself probably evolved from Megantereon. The hundreds of specimens obtained from the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles constitute the largest collection of Smilodon fossils.

Panthera spelaea, also known as the cave lion or steppe lion, is an extinct Panthera species that most likely evolved in Europe after the third Cromerian interglacial stage, less than 600,000 years ago. Genetic analysis of ancient DNA has revealed that while closely related, it was a distinct species genetically isolated from the modern lion occurring in Africa and Asia, with the genetic divergence between the two species variously estimated between 1.9 million and 600,000 years ago. It is closely related and probably ancestral to the American lion. The species ranged from Western Europe to eastern Beringia in North America, and was a prominent member of the mammoth steppe fauna. It became extinct about 13,000 years ago.

The Pantherinae is a subfamily of the Felidae; it was named and first described by Reginald Innes Pocock in 1917 as only including the Panthera species. The Pantherinae genetically diverged from a common ancestor between 9.32 to 4.47 million years ago and 10.67 to 3.76 million years ago.

The history of lions in Europe is based on fossils of Pleistocene and Holocene lions excavated in Europe since the early 19th century. The first lion fossil was excavated in southern Germany, and described by Georg August Goldfuss using the scientific name Felis spelaea. It probably dates to the Würm glaciation, and is 191,000 to 57,000 years old. Older lion skull fragments were excavated in Germany and described by Wilhelm von Reichenau under Felis fossilis in 1906. These are estimated at between 621,000 and 533,000 years old. The modern lion inhabited parts of Southern Europe since the early Holocene.

Panthera gombaszoegensis, also known as the European jaguar, is a Panthera species that lived from about 2.0 to 0.35 million years ago in Europe The first fossils were excavated in 1938 in Gombasek, Slovakia. P. gombaszoegensis was medium-large sized species that formed an important part of the European carnivore guild for a period of over a million years. Many authors have posited that the species is the ancestor of the American jaguar, with some authors considering it the subspecies Panthera onca gombaszoegensis, though the close relationship between the two species has been questioned.

Panthera youngi is a fossil cat species that was described in 1934; fossil remains of this cat were excavated in a Homo erectus formation in Choukoutien, northeastern China. Upper and lower jaws excavated in Japan's Yamaguchi Prefecture were also attributed to this species. It is estimated to have lived about 350,000 years ago in the Pleistocene epoch. It was suggested that it was conspecific with Panthera atrox and P. spelaea due to their extensive similarities. Some dental similarities were also noted with the older P. fossilis, however, Panthera youngi showed more derived features.

Panthera fossilis, is an extinct species of cat belonging to the genus Panthera, known from remains found in Eurasia spanning the Middle Pleistocene and possibly into the Early Pleistocene. P. fossilis has sometimes been referred to by the common names steppe lion or cave lion, though these names are conventionally restricted to the later related species P. spelaea, to which P. fossilis is probably ancestral.

Cave lions are large extinct carnivorous felids that are classified either as subspecies of the lion, or as distinct but closely related species, depending on the authority.

Panthera onca mesembrina is an extinct subspecies of jaguar that was endemic to Patagonia in southern South America during the late Pleistocene epoch. It is known from several fragmentary specimens, the first of which found was in 1899 at "Cueva del Milodon" in Chile. These fossils were referred to a new genus and species "Iemish listai" by naturalist Santiago Roth, who thought they might be the bones of the mythological iemisch of Tehuelche folklore. A later expedition recovered more bones, including the skull of a large male that was described in detail by Angel Cabrera in 1934. Cabrera created a new name for the giant felid remains, Panthera onca mesembrina, after realizing that its fossils were near-identical to modern jaguars’. P. onca mesembrina's validity is disputed, with some paleontologists suggesting that it is a synonym of Panthera atrox.

Panthera onca augusta is an extinct subspecies of the jaguar that was endemic to North America during the Pleistocene epoch.

Panthera pardus spelaea, also known as the European Ice Age leopard, is a fossil leopard subspecies which roamed Europe in the Late Pleistocene and possibly the Holocene.

Panthera blytheae is an extinct species of pantherine felid that lived during the late Messinian to early Zanclean ages approximately 5.95–4.1 million years ago.The first fossils were excavated in August 2010 in the Zanda Basin located in the Ngari Prefecture on the Tibetan Plateau; they were described and named in 2014.

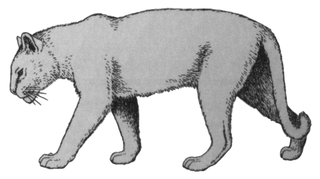

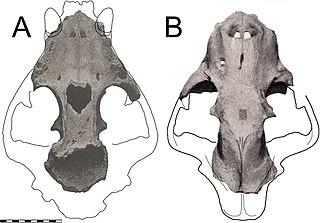

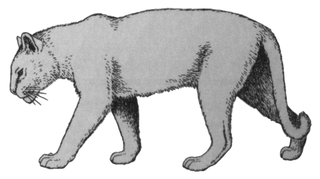

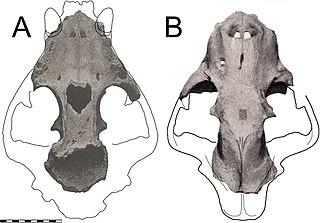

Sivapanthera is a prehistoric genus of felid described by Kretzoi in 1929. Species of Sivapanthera are closely related to the modern cheetah but differ from modern cheetahs by having relatively longer brain cases, flatter foreheads, narrower nostrils and larger teeth. In many ways, skulls of Sivapanthera show similarity to that of the puma, or even those of Panthera. Scholars differ on the validity of this genus, while some think that it should be treated as a distinct genus, others think that its members should be treated as members of the Acinonyx genus, or even as subspecies of Acinonyx pardinensis.

Panthera shawi is an extinct prehistoric cat, of which a single canine tooth was excavated in Sterkfontein cave in South Africa by Robert Broom in the 1940s. It is thought to be the oldest known Panthera species in Africa.

Panthera balamoides is a species described as an extinct species of the big cat genus Panthera that is known from a single fossil found in a Late Pleistocene age cenote in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. P. balamoides has only a single reported specimen, the distal end of a right humerus, that is notably of exceptional size for a felid. It was unearthed in 2012 from an underwater cave and described in 2019 by an international group of paleontologists from Mexico and Germany led by Sarah R. Stinnesbeck. However, several authors have since proposed that the fossil comes from an ursid, possibly the extinct Arctotherium, and not of felid affinities.