Kuwait is a sovereign state in Western Asia located at the head of the Persian Gulf. The geographical region of Kuwait has been occupied by humans since antiquity, particularly due to its strategic location at the head of the Persian Gulf. In the pre-oil era, Kuwait was a maritime port city. In the modern era, Kuwait is best known for the Gulf War (1990–1991).

The history of Qatar spans from its first duration of human occupation to its formation as a modern state. Human occupation of Qatar dates back to 50,000 years ago, and Stone Age encampments and tools have been unearthed in the Arabian Peninsula. Mesopotamia was the first civilization to have a presence in the area during the Neolithic period, evidenced by the discovery of potsherds originating from the Ubaid period near coastal encampments.

Zubarah, also referred to as Al Zubarah or Az Zubarah, is a ruined and ancient fort located on the north western coast of the Qatar peninsula in the Al Shamal municipality, about 65 miles from the Qatari capital of Doha. It was founded by Shaikh Muhammed bin Khalifa, the founder father of Al Khalifa royal family of Bahrain, the main and principal Utub tribe in the first half of the eighteenth century. It was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2013.

Frank Holmes, known affectionately by Arabs as "Abu Naft", was a British-New Zealand mining engineer, geologist and oil concession hunter. Following distinguished service in World War I, he was granted the title of honorary Major and was thereafter known as Major Frank Holmes in his civilian life.

Kaymakam, also known by many other romanizations, was a title used by various officials of the Ottoman Empire, including acting grand viziers, governors of provincial sanjaks, and administrators of district kazas. The title has been retained and is sometimes used without translation for provincial or subdistrict governors in various Ottoman successor states, including the Republic of Turkey, Kuwait, Iraq, and Lebanon.

Ḥakīm and Ḥākim are two Arabic titles derived from the same triliteral root Ḥ-K-M "appoint, choose, judge".

Sheikh Mubarak Al-Sabah "the Great", nicknamed "The lion of the peninsula", was the seventh ruler of the Sheikhdom of Kuwait, from 18 May 1896 until his death on 18 November 1915. Mubarak ascended the throne upon killing his half-brother, Muhammad Al-Sabah. Known for his significant role in shaping modern Kuwait, the constitution of the State of Kuwait mandates that the Emir of Kuwait must be a descendant of Mubarak from the ruling Al-Sabah family.

The Basra Vilayet was a first-level administrative division (vilayet) of the Ottoman Empire. It historically covered an area stretching from Nasiriyah and Amarah in the north to Kuwait in the south. To the south and the west, there was theoretically no border at all, yet no areas beyond Qatar in the south and the Najd Sanjak in the west were later on included in the administrative system.

The Persian Gulf Residency was a subdivision of the British Empire from 1822 until 1971, whereby the United Kingdom maintained varying degrees of political and economic control over several states in the Persian Gulf, including what is today known as the United Arab Emirates and at various times southern portions of Iran, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar.

Al-Aḥsāʾ, also known as al-Ḥasāʾ (الْحَسَاء) or Hajar (هَجَر), is an oasis and historical region in eastern Saudi Arabia. Al-Ahsa Governorate, which makes up much of the country's Eastern Province, is named after it. The oasis is located about 60 km (37 mi) inland from the coast of the Persian Gulf. Al-Ahsa Oasis comprises four main cities and 22 villages. The cities include Al-Mubarraz and Al-Hofuf, two of the largest cities in Saudi Arabia.

Khawr al Udayd, is a settlement and inlet of the Persian Gulf located in Al Wakrah Municipality in southeast Qatar, on the border with Saudi Arabia. It is known to local English speakers as the "Inland Sea". In the past it accommodated a small town and served as the center of a long-running territorial dispute between Sheikh Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani and Sheikh Zayed bin Khalifa Al Nahyan. At the present, it is a major tourist destination for Qatar.

This article deals with territorial disputes between states of in and around the Persian Gulf in Southwestern Asia. These states include Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Oman.

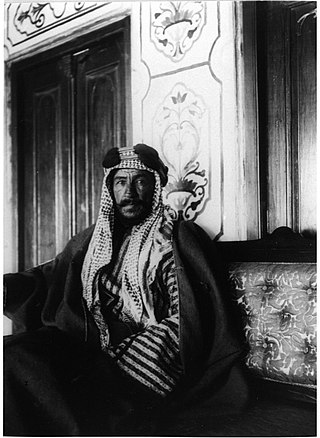

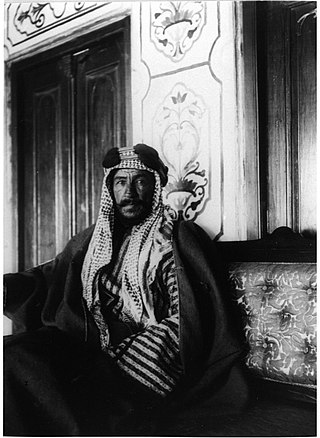

Sheikh Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani, also known as "The Founder", was the founder of the State of Qatar. He had a total of 56 children, 19 sons and 37 daughters.

The Sheikhdom of Kuwait was a sheikhdom which gained independence from the Khalidi Emirate of Al Hasa under Sabah I bin Jaber in the year 1752. The Sheikhdom became a British protectorate between 1899 and 1961 following the Anglo-Kuwaiti agreement of 1899. This agreement was made between Sheikh Mubarak Al-Sabah and the British Government in India, primarily as a defensive measure against threats to Kuwait's independence emanating from the Ottoman Empire.

The sanjak of Najd was a sanjak of the Ottoman Empire. The name is considered misleading, as it covered the al-Hasa region, rather than the much larger Najd region. It was part of Baghdad Vilayet from June 1871 to 1875, when it became part of the Basra Vilayet.

The Battle of Al Wajbah was an armed conflict that took place in March 1893 in Qatar, a province of the Ottoman Empire's Najd sanjak at that time. The conflict was initiated after Ottoman officials imprisoned 16 Qatari tribal leaders and ordered a column of troops to march toward the Al Thani stronghold in the village of Al Wajbah in response to kaymakam Jassim Al Thani's refusal to come to Ottoman authority.

The Anglo-Kuwaiti Agreement of 1899 was a secret treaty signed between the British Empire and the Sheikhdom of Kuwait on 23 January 1899. Under its provisions Britain pledged to protect the territorial integrity of Kuwait in return for restricting the access of foreign powers to the Sheikhdom and regulating its internal affairs.

The Iraq–Kuwait border is 254 km in length and runs from the tripoint with Saudi Arabia in the west to the Persian Gulf coast in the east.

The Qatar–Saudi Arabia border is 87 km (54 mi) in length and runs from the Gulf of Bahrain coast in the west to the Persian Gulf coast in the east.

The Al-Hasa Expedition was an Ottoman military campaign to annex the El-Hasa region of eastern Arabia. Ostensibly launched to assist Imam Abdullah bin Faisal in reclaiming control over Najd from his brother Saud bin Faisal, the underlying motive was Medhat Pasha's ambition to extend Ottoman dominion over the Persian Gulf.