First Treaty of 1823

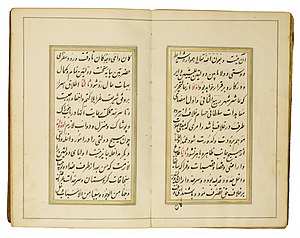

An official copy of the First Treaty of Erzurum. Persian manuscript, created in Qajar Iran, 19th century | |

| Type | Bilateral treaty |

|---|---|

| Signed | July 29, 1823 |

| Location | Erzurum, Ottoman Empire |

| Parties | |

Throughout history, there has been a constant primary concern of establishing an end to all hostility between the Ottoman Empire and Qajar Persia. Tensions between the two empires had been rising due to the Ottoman Empire's actions of harboring and withholding rebellious tribesmen from the Iranian Azerbaijan Province, which sparked issues with the Kurds. This tension led to an outbreak of wars between the two empires. The Persian also felt that their rights were being violated through unfair treatment by the Ottomans while the Ottomans struggled to view the Persian with respect and were not fond of their eastern neighbors until the Treaties of Erzurum were put in effect. With a goal of reaching a state of tranquility, it was attempted throughout multiple treaties that have all had the same objective in mind of achieving peace dating back to the Treaty of Zuhab in 1639 and leading all the way up to the final Treaty of Erzurum in 1848. Although the Treaty of Zuhab had established the boundary between the Ottoman Empire and Persia, the only clause that was stated in the treaty was that merchants from both realms could pass unharmed and unhampered into the lands of the other. [2] Although, the border in the mountainous Zuhab region remained a site of intermittent conflict in the subsequent two centuries. Over a century later, there were three issues that were still concerning Iranians the most: the levying of unfair taxes on pilgrims, the imposition of the jizya (the head tax on all adult male non-Muslims) on Iranian dhimmis, and the confiscation of the estates of deceased Iranian subjects. [2] Attempting to resolve these issues, the problem was addressed with the Treaty of Kerden in 1746, which affirmed the right of Iranian pilgrims to travel freely and limited the amount of custom duties they could be charged. This treaty, however, did not end the abuse of Iranian Muslims by Ottoman officials which is what led to continuous tension between the two states and what led to Karim Khan Zand invading Ottoman, Iraq in 1776 in attempt to punish the Ottomans for infractions of the treaty. [1] To add on top of that, the Russian Empire was secretly also attempting to put pressure on the Ottoman Empire, who was at war with the Greeks, whom were receiving arms from Russia. [3] At the instigation of the actions of the Russian Empire, Crown Prince Abbas Mirza of Persia, invaded Kurdistan and the areas surrounding Persian Azerbaijan, which led to the commencement of the Ottoman–Persian War. [3]

After the 1821 Battle of Erzurum, resulting in a Persian victory, both empires signed the first Treaty of Erzurum on July 1823, which confirmed the 1639 border. This treaty was composed of 21 leaves, 2 flyleaves, with 11 lines to the page. It was written in nasta'liq ink with the keywords highlighted in red catchwords, margins ruled in gold, and a camel-colored leather binding including an outer hard cover with a ribbon. The treaty had one main primary goal which was to re-establish the state of affairs that existed previously along the troublesome Kurdish frontier, where the Ottoman client state of Baban had just endured a civil war between pro-shah and pro-sultan factions, however the Iranians also wanted to achieve some purely economic objectives in their negotiations. [1] The treaty contained various economic and diplomatic clauses which stated that firstly, Iranian pilgrims would not be subjected to any extraordinary taxes that were ordinary to the Ottoman Empire and that their trade goods would be taxed at a fair and consistent rate. Secondly, the treaty regulated the taxes concerning the pilgrims and for the nomadic tribes pasturing their livestock in the borderlands. [4] There was a specific flat tax rate of 4% that was in direct proportion to the amount of goods that were being transported, which was collected at the first entry point of the merchant, likely Baghdad or Erzurum, or at Istanbul and the money would then be forwarded to Istanbul as part of the province's revenues. [1] There was also the regulation of the taxes concerning the pilgrims and for the nomadic tribes pasturing their livestock in the borderlands. [4] Thirdly, the treaty also allowed for Iranian merchants to freely trade in glass water pipes from Persia to Istanbul. Fourthly, Iranians wanted reforms to be instituted in the ways in which the estates of Iranians who died in the Ottoman Empire were handled. [1] Also included in the treaty, was the guaranteed access for Persian pilgrims to visit holy sites within the Ottoman Empire. [3] This had previously been promised by the 1746 Treaty of Kerden, but those rights had degraded over time. [1]

With the new Treaty in effect, there was a subtle progression in the way that the Ottomans viewed Persia. There was a shift from sectarian invectives from the 1746 Treaty of Kerden which were not in high favor of the Persian people that were not present in the Treaty of Erzurum. [1] Perhaps the clearest indication of change in the ways that the Ottomans perceived their eastern neighbors was the addition of Iran in 1823 to the list of countries which the bureaucrats at the Porte maintained separate registers of cases involving its citizens who needed state intervention. Although there was no guarantee of extraterritoriality in the treaty, the Ottoman bureaucrats started recognizing Iran as a separate nation whose subjects could call upon the central government for redress if their individual rights had been violated under the treaty - a privilege formerly only offered to European nations. [1] Iran was the first and only Muslim state to achieve this recognition from Istanbul. [1] There was also an agreement that every three years, Persia, as well as the Ottomans would send an envoy to the other country, therefore establishing permanent diplomatic relations with each other. [4]