Angola is a village in the town of Evans in Erie County, New York, United States. Located 2 miles (3 km) east of Lake Erie, the village is 22 miles (35 km) southwest of downtown Buffalo. As of the 2010 Census, Angola had a population of 2,127. An unincorporated community known as Angola on the Lake, with a population of 1,675, lies between Angola village and Lake Erie.

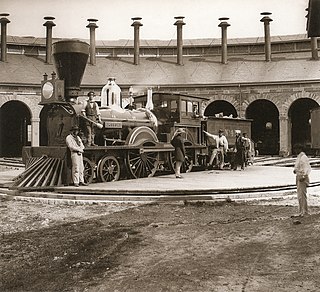

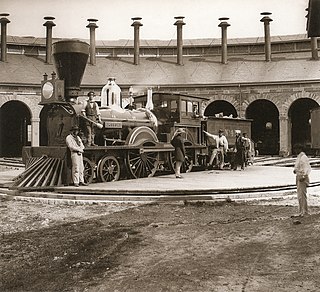

The Erie Railroad was a railroad that operated in the Northeastern United States, originally connecting Pavonia Terminal in Jersey City, New Jersey, with Lake Erie at Dunkirk, New York. The railroad expanded west to Chicago following its 1865 merger with the former Atlantic and Great Western Railroad, also known as the New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio Railroad. Its mainline route proved influential in the development and economic growth of the Southern Tier of New York state, including the cities of Binghamton, Elmira, and Hornell. The Erie Railroad repair shops were located in Hornell and was Hornell's largest employer. Hornell was also where Erie's mainline split into two routes with one proceeding northwest to Buffalo and the other west to Chicago.

The Great Western Railway was a railway that operated in Canada West, today's province of Ontario, Canada. It was the first railway chartered in the province, receiving its original charter as the London and Gore Railroad on March 6, 1834, before receiving its final name when it was rechartered in 1845.

On February 6, 1951, a Pennsylvania Railroad train derailed on a temporary wooden trestle in Woodbridge, New Jersey, United States, killing 85 passengers. It remains New Jersey's deadliest train wreck, the deadliest U.S. derailment since 1918 and the deadliest peacetime rail disaster in the U.S. history.

The Connellsville train wreck was a rail accident that occurred on December 23, 1903, on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad near Connellsville, Pennsylvania. The Duquesne Limited, a passenger train, derailed when it struck a load of timber lying on the tracks. The timber had fallen from a freight train minutes before the collision. The crash resulted in 64 deaths and 68 injuries.

The Corning train wreck was a railway accident that occurred at 5.21 a.m. on July 4, 1912, on the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad at East Corning freight station in Gibson three miles east of Corning in New York State, leaving 39 dead and 88 injured.

During the evening rush hour on August 24, 1928, an express subway train derailed immediately after leaving the Times Square station on the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line. Sixteen people were killed at the scene, two died later, and about 100 were injured. It remains the second-deadliest accident on the New York City Subway system, after the Malbone Street Wreck.

On April 14, 1907, northbound freight train No.23 of the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad, operating on the Rome and Richland branch of the former Rome, Watertown and Ogdensburg Railroad crashed when the bank on the lower side of the track failed and a section slid down the hill undermining the track. The accident occurred approximately 2.5 miles south of Blossvale, a hamlet in the Oneida County, New York, town of Annsville. The sixty-car freight train, carrying coal and other freight was pulled by engines No. 1726 and 1863. Both engines plunged down the sixty foot embankment. The lead engine came to rest in an inverted position while the second engine was on its side. Both engines and several cars were destroyed by fire. In addition to the two engines, a total of fifteen cars derailed.

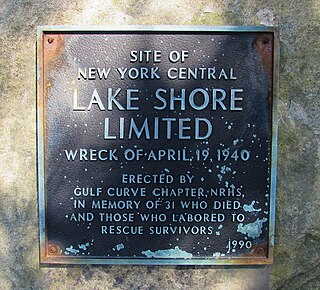

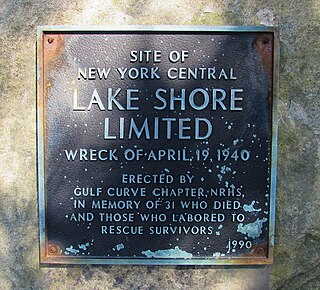

A train crash with fatalities occurred shortly after 11:30 p.m. on April 19, 1940, when a first-class westbound Lake Shore Limited operated by the New York Central Railroad, derailed near Little Falls, New York, United States. The accident was later found to have occurred due to excessive speed on the Gulf Curve, the sharpest on the Central's lines. It killed 31; an additional 51 were injured.

On August 12, 1939, the City of San Francisco train derailed outside of Harney, Nevada, United States, killing 24 and injuring 121 passengers and crew. The derailment was caused by sabotage of the tracks. Despite a manhunt, reward offers, and years of investigation by the Southern Pacific Railroad (SP), the case remains unsolved.

The Lackawanna Limited wreck occurred when a Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad (DL&W) passenger train, the New York-Buffalo Lackawanna Limited with 500 passengers, crashed into a freight train on August 30, 1943, killing 29 people in the small Steuben County community of Wayland in upstate New York, approximately 40 miles (64 km) south of Rochester.

In 1890 a railway accident in Quincy, Massachusetts killed 23 people. It was the second major train wreck in the city, following the 1878 accident in Wollaston. The accident was caused by a jack that had been left on the track. The foreman of the crew that placed the jack on the track was charged with manslaughter, but the trial ended in a hung jury.