Watling Street is a historic route in England that crosses the River Thames at London and which was used in Classical Antiquity, Late Antiquity, and throughout the Middle Ages. It was used by the ancient Britons and paved as one of the main Roman roads in Britannia. The route linked Dover and London in the southeast, and continued northwest via St Albans to Wroxeter. The line of the road was later the southwestern border of the Danelaw with Wessex and Mercia, and Watling Street was numbered as one of the major highways of medieval England.

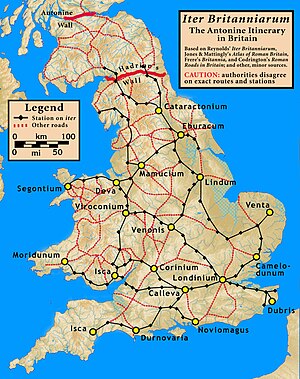

Roman roads in Britannia were initially designed for military use, created by the Roman army during the nearly four centuries (AD 43–410) that Britannia was a province of the Roman Empire.

High Cross is the name given to the crossroads of the Roman roads of Watling Street and Fosse Way on the border between Leicestershire and Warwickshire, England. A naturally strategic high point, High Cross was "the central cross roads" of Anglo-Saxon and Roman Britain. It was the site of a Romano-British settlement known as Venonae or Venonis, with an accompanying fort.

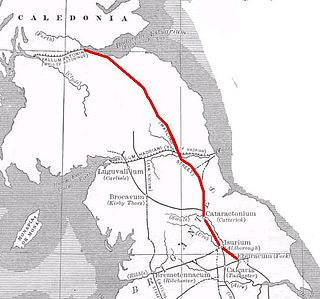

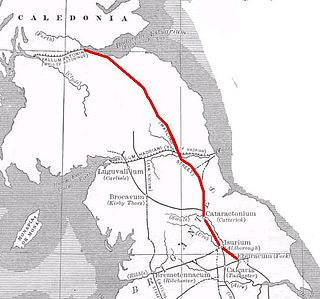

Dere Street or Deere Street is a modern designation of a Roman road which ran north from Eboracum (York), crossing the Stanegate at Corbridge and continuing beyond into what is now Scotland, later at least as far as the Antonine Wall. It was the Romans' major route for communications and supplies to the north and to Scotland. Portions of its route are still followed by modern roads, including the A1(M), the B6275 road through Piercebridge, where Dere Street crosses the River Tees, and the A68 north of Corbridge in Northumberland.

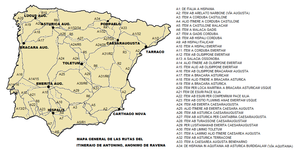

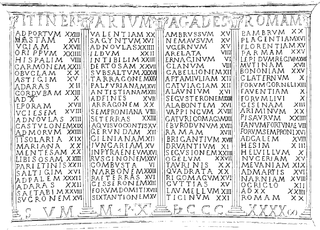

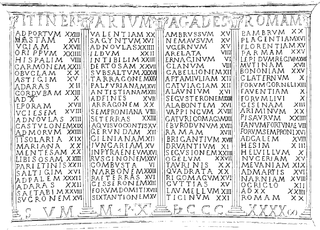

An itinerarium was an ancient Roman travel guide in the form of a listing of cities, villages (vici) and other stops on the way, including the distances between each stop and the next. Surviving examples include the Antonine Itinerary and the Bordeaux Itinerary.

Durobrivae was a Roman fortified garrison town located at Water Newton in the English county of Cambridgeshire, where Ermine Street crossed the River Nene. More generally, it was in the territory of the Corieltauvi in a region of villas and commercial potteries. The name is a Latinisation of Celtic *Durobrīwās, meaning essentially "fort bridges".

Thomas Gale was an English classical scholar, antiquarian and cleric.

Ancaster was a small town in the Roman province of Britannia. It is sited on the Roman road known as the Ermine Street and is situated in the county of Lincolnshire. Its name in Latin is unknown, although it has traditionally been identified with Causennis or Causennæ, a name which occurs as a town on the route of Iter V recorded in the Antonine Itinerary. Rivet and Smith questioned this identification in 1979, and suggested that a more likely identification would be either the Roman settlement at Salters ford, near Grantham in Lincolnshire, or at Sapperton in Lincolnshire.

Steep Hill is a street in the historic city of Lincoln, Lincolnshire, England. At the top of the hill is the entrance to Lincoln Cathedral and at the bottom is Well Lane. The Hill consists of independent shops, tea rooms and pubs.

The Description of Britain, also known by its Latin name De Situ Britanniae, was a literary forgery perpetrated by Charles Bertram on the historians of England. It purported to be a 15th-century manuscript by the English monk Richard of Westminster, including information from a lost contemporary account of Britain by a Roman general, new details of the Roman roads in Britain in the style of the Antonine Itinerary, and "an antient map" as detailed as the works of Ptolemy. Bertram disclosed the existence of the work through his correspondence with the antiquarian William Stukeley by 1748, provided him "a copy" which was made available in London by 1749, and published it in Latin in 1757. By this point, his Richard had become conflated with the historical Richard of Cirencester. The text was treated as a legitimate and major source of information on Roman Britain from the 1750s through the 19th century, when it was progressively debunked by John Hodgson, Karl Wex, B. B. Woodward, and John E. B. Mayor. Effects from the forgery can still be found in works on British history and it is generally credited with having named the Pennine Mountains.

Ariconium was a road station of Roman Britain mentioned in Iter XIII of the Iter Britanniarum of the Antonine Itineraries. It was located at Bury Hill in the parish of Weston under Penyard, about 3 miles (5 km) east of Ross on Wye, Herefordshire, and about 15 miles (24 km) southeast of Hereford. The site existed prior to the Roman era, and then came under Roman control. It was abandoned, perhaps shortly after 360, but precisely when and under what circumstances is unknown.

Thomas Reynolds (1752–1829) was an English antiquarian and minister.

Caenophrurium was a settlement in the Roman province of Europa, between Byzantium and Heraclea Perinthus. It appears in late Roman and early Byzantine accounts. Caenophrurium translates as the "stronghold of the Caeni", a Thracian tribe.

Noviomagus is a Latinization of a Brittonic placename meaning "new plain" or "new fields", a clearing in woodland. The element Cantiacorum distinguishes it from other places with the name Noviomagus. It was a Roman settlement in southeastern Britain, named on Iter II of the Antonine Itinerary, ten Roman miles from Londinium and nineteen to Vagniacis, thence nine miles to Durobrivae. Its location has been given as modern Crayford, but is now suggested to be near West Wickham following excavation of the Roman site there; the distances also fit West Wickham better than Crayford.

Vespasiana was a fictional 4th-century Roman province in Caledonia that appeared in Charles Bertram's 18th-century forgery On the State of Britain, which purported to be "Richard of Westminster"'s 14th-century retelling of a Roman general's contemporary account of Britain in late antiquity.

Tigisis, also known as Tigisis in Mauretania to distinguish it from another Tigisis in Numidia, was an ancient Berber town in the province of Mauretania Caesariensis. It was mentioned in the Antonine Itinerary.

Tocolsida is a site in modern Morocco, with the remains of an ancient castra from the Roman Province of Mauretania Tingitana, Roman Empire.

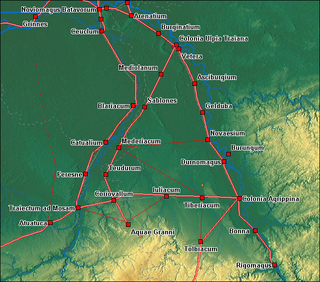

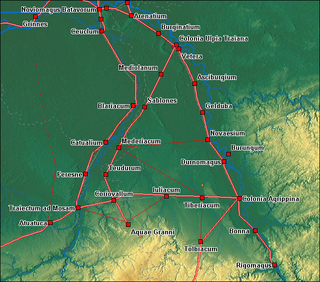

Sablones was a Roman settlement in the province of Germania Inferior, probably near modern-day Kaldenkirchen in Germany, just across the border from Venlo in the Netherlands. The statio is mentioned in the Roman travel guide Antonine Itinerary (Itinerarium Antonini) between Meridacium and Mediolanum and was located on the Roman road from Coriovallum (Heerlen) to Colonia Ulpia Traiana (Xanten).

The Via Nova or Via XVIII in the Antonine Itinerary is a Roman road which linked the cities of Bracara Augusta and Asturica Augusta, with a length of about 210 roman miles.

An ancient Roman statio was a stopping place on a Roman road for travellers looking for shelter for the night and a change of horses. The name of the statio was sometimes a town or city with suitable accommodation, such as inns, and sometimes a dedicated building between larger settlements. They often included thermal baths in the facilities.