Astronomy is the oldest of the natural sciences, dating back to antiquity, with its origins in the religious, mythological, cosmological, calendrical, and astrological beliefs and practices of prehistory: vestiges of these are still found in astrology, a discipline long interwoven with public and governmental astronomy. It was not completely separated in Europe during the Copernican Revolution starting in 1543. In some cultures, astronomical data was used for astrological prognostication.

Johannes Kepler was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws of planetary motion, and his books Astronomia nova, Harmonice Mundi, and Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae, influencing among others Isaac Newton, providing one of the foundations for his theory of universal gravitation. The variety and impact of his work made Kepler one of the founders and fathers of modern astronomy, the scientific method, natural and modern science.

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology and chemistry transformed the views of society about nature. The Scientific Revolution took place in Europe in the second half of the Renaissance period, with the 1543 Nicolaus Copernicus publication De revolutionibus orbium coelestium often cited as its beginning.

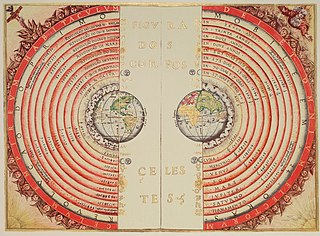

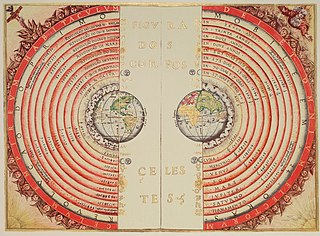

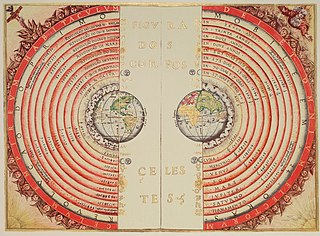

In astronomy, the geocentric model is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, and planets all orbit Earth. The geocentric model was the predominant description of the cosmos in many European ancient civilizations, such as those of Aristotle in Classical Greece and Ptolemy in Roman Egypt, as well as during the Islamic Golden Age.

In the Hipparchian, Ptolemaic, and Copernican systems of astronomy, the epicycle was a geometric model used to explain the variations in speed and direction of the apparent motion of the Moon, Sun, and planets. In particular it explained the apparent retrograde motion of the five planets known at the time. Secondarily, it also explained changes in the apparent distances of the planets from the Earth.

Simon Marius was a German astronomer. He was born in Gunzenhausen, near Nuremberg, but spent most of his life in the city of Ansbach. He is best known for being among the first observers of the four largest moons of Jupiter, and his publication of his discovery led to charges of plagiarism.

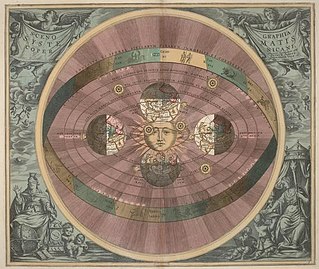

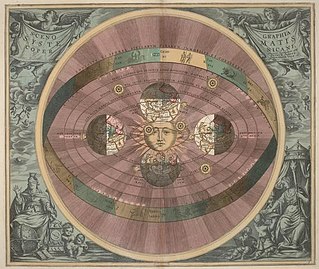

Heliocentrism is a superseded astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth at the center. The notion that the Earth revolves around the Sun had been proposed as early as the third century BC by Aristarchus of Samos, who had been influenced by a concept presented by Philolaus of Croton. In the 5th century BC the Greek Philosophers Philolaus and Hicetas had the thought on different occasions that the Earth was spherical and revolving around a "mystical" central fire, and that this fire regulated the universe. In medieval Europe, however, Aristarchus' heliocentrism attracted little attention—possibly because of the loss of scientific works of the Hellenistic period.

The Tychonic system is a model of the universe published by Tycho Brahe in the late 16th century, which combines what he saw as the mathematical benefits of the Copernican system with the philosophical and "physical" benefits of the Ptolemaic system. The model may have been inspired by Valentin Naboth and Paul Wittich, a Silesian mathematician and astronomer. This cosmological model is the same as the one proposed in the Hindu astronomical treatise Tantrasamgraha by Nilakantha Somayaji of the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics.

In astronomy, the fixed stars are the luminary points, mainly stars, that appear not to move relative to one another against the darkness of the night sky in the background. This is in contrast to those lights visible to naked eye, namely planets and comets, that appear to move slowly among those "fixed" stars.

Giovanni Battista Riccioli, SJ was an Italian astronomer and a Catholic priest in the Jesuit order. He is known, among other things, for his experiments with pendulums and with falling bodies, for his discussion of 126 arguments concerning the motion of the Earth, and for introducing the current scheme of lunar nomenclature. He is also widely known for discovering the first double star. He argued that the rotation of the Earth should reveal itself because on a rotating Earth, the ground moves at different speeds at different times.

The Copernican Revolution was the paradigm shift from the Ptolemaic model of the heavens, which described the cosmos as having Earth stationary at the center of the universe, to the heliocentric model with the Sun at the center of the Solar System. This revolution consisted of two phases; the first being extremely mathematical in nature and the second phase starting in 1610 with the publication of a pamphlet by Galileo. Beginning with the publication of Nicolaus Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, contributions to the “revolution” continued until finally ending with Isaac Newton’s work over a century later.

The Galileo affair began around 1610 and culminated with the trial and condemnation of Galileo Galilei by the Roman Catholic Inquisition in 1633. Galileo was prosecuted for his support of heliocentrism, the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the centre of the universe.

Copernican heliocentrism is the astronomical model developed by Nicolaus Copernicus and published in 1543. This model positioned the Sun at the center of the Universe, motionless, with Earth and the other planets orbiting around it in circular paths, modified by epicycles, and at uniform speeds. The Copernican model displaced the geocentric model of Ptolemy that had prevailed for centuries, which had placed Earth at the center of the Universe.

Galileo's Daughter: A Historical Memoir of Science, Faith, and Love is a book by Dava Sobel published in 1999. It is based on the surviving letters of Galileo Galilei's daughter, the nun Suor Maria Celeste, and explores the relationship between Galileo and his daughter. It was nominated for the 2000 Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography.

Discovery and exploration of the Solar System is observation, visitation, and increase in knowledge and understanding of Earth's "cosmic neighborhood". This includes the Sun, Earth and the Moon, the major planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, their satellites, as well as smaller bodies including comets, asteroids, and dust.

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei, commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei or simply Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. He was born in the city of Pisa, then part of the Duchy of Florence. Galileo has been called the father of observational astronomy, modern-era classical physics, the scientific method, and modern science.

The center of the Universe is a concept that lacks a coherent definition in modern astronomy; according to standard cosmological theories on the shape of the universe, it has no center.

Jacques du Chevreul was a French mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher.

Historical models of the Solar System began during prehistoric periods and are updated to this day. The models of the Solar System throughout history were first represented in the early form of cave markings and drawings, calendars and astronomical symbols. Then books and written records became the main source of information that expressed the way the people of the time thought of the Solar System.