Fijian is an Austronesian language of the Malayo-Polynesian family spoken by some 350,000–450,000 ethnic Fijians as a native language. The 2013 Constitution established Fijian as an official language of Fiji, along with English and Fiji Hindi and there is discussion about establishing it as the "national language". Fijian is a VOS language.

Manam is a Kairiru–Manam language spoken mainly on the volcanic Manam Island, northeast of New Guinea.

Tamambo, or Malo, is an Oceanic language spoken by 4,000 people on Malo and nearby islands in Vanuatu. It is one of the most conservative Southern Oceanic languages.

Araki is a nearly extinct language spoken in the small island of Araki, south of Espiritu Santo Island in Vanuatu. Araki is gradually being replaced by Tangoa, a language from a neighbouring island.

Yabem, or Jabêm, is an Austronesian language of Papua New Guinea.

Ughele is an Oceanic language spoken by about 1200 people on Rendova Island, located in the Western Province of the Solomon Islands.

Iraqw is a Cushitic language spoken in Tanzania in the Arusha and Manyara Regions. It is expanding in numbers as the Iraqw people absorb neighbouring ethnic groups. The language has many Datooga loanwords, especially in poetic language. The Gorowa language, to the south, shares numerous similarities and is sometimes considered a dialect.

Adang is a Papuan language spoken on the island of Alor in Indonesia. The language is agglutinative. The Hamap dialect is sometimes treated as a separate language; on the other hand, Kabola, which is sociolinguistically distinct, is sometimes included. Adang, Hamap and Kabola are considered a dialect chain. Adang is endangered as fewer speakers raise their children in Adang, instead opting for Indonesian.

Guanano (Wanano), or Piratapuyo, is a Tucanoan language spoken in the northwest part of Amazonas in Brazil and in Vaupés in Colombia. It is spoken by two peoples, the Wanano and the Piratapuyo. They do not intermarry, but their speech is 75% lexically similar.

Tundra Nenets is a Uralic language spoken in European Russia and North-Western Siberia. It is the largest and best-preserved language in the Samoyedic group.

Buru or Buruese is a Malayo-Polynesian language of the Central Maluku branch. In 1991 it was spoken by approximately 45,000 Buru people who live on the Indonesian island of Buru. It is also preserved in the Buru communities on Ambon and some other Maluku Islands, as well as in the Indonesian capital Jakarta and in the Netherlands.

Mavea is an Oceanic language spoken on Mavea Island in Vanuatu, off the eastern coast of Espiritu Santo. It belongs to the North–Central Vanuatu linkage of Southern Oceanic. The total population of the island is approximately 172, with only 34 fluent speakers of the Mavea language reported in 2008.

Dom is a Trans–New Guinea language of the Eastern Group of the Chimbu family, spoken in the Gumine and Sinasina Districts of Chimbu Province and in some other isolated settlements in the western highlands of Papua New Guinea.

Tiri, or Mea, is an Oceanic language of New Caledonia.

Vamale (Pamale) is a Kanak language of northern New Caledonia. The Hmwaeke dialect, spoken in Tiéta, is fusing with Haveke and nearly extinct. Vamale is nowadays spoken in Tiendanite, We Hava, Téganpaïk and Tiouandé. It was spoken in the Pamale valley and its tributaries Vawe and Usa until the colonial war of 1917, when its speakers were displaced.

Merei or Malmariv is an Oceanic language spoken in north central Espiritu Santo Island in Vanuatu.

North Ambrym is a language of Ambrym Island, Vanuatu.

Zoogocho Zapotec, or Diža'xon, is a Zapotec language of Oaxaca, Mexico.

Karipúna French Creole, also known as Amapá French Creole and Lanc-Patuá, is a French-based creole language spoken by the Karipúna community, which lives in the Uaçá Indian Reservation in the Brazilian state of Amapá, on the Curipi and Oyapock rivers. It is mostly French-lexified except for flora and fauna terms, with a complex mix of substratum languages—most notably the Arawakan Karipúna language.

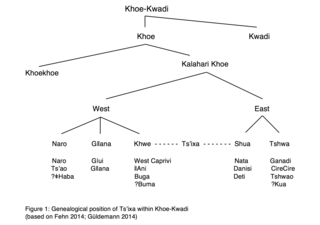

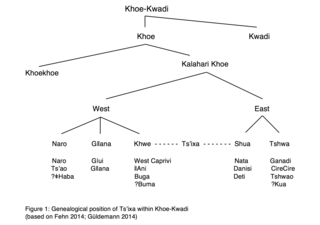

Tsʼixa is a critically endangered African language that belongs to the Kalahari Khoe branch of the Khoe-Kwadi language family. The Tsʼixa speech community consists of approximately 200 speakers who live in Botswana on the eastern edge of the Okavango Delta, in the small village of Mababe. They are a foraging society that consists of the ethnically diverse groups commonly subsumed under the names "San", "Bushmen" or "Basarwa". The most common term of self-reference within the community is Xuukhoe or 'people left behind', a rather broad ethnonym roughly equaling San, which is also used by Khwe-speakers in Botswana. Although the affiliation of Tsʼixa within the Khalari Khoe branch, as well as the genetic classification of the Khoisan languages in general, is still unclear, the Khoisan language scholar Tom Güldemann posits in a 2014 article the following genealogical relationships within Khoe-Kwadi, and argues for the status of Tsʼixa as a language in its own right. The language tree to the right presents a possible classification of Tsʼixa within Khoe-Kwadi: