Karachay-Cherkessia, officially the Karachay-Cherkess Republic, is a republic of Russia located in the North Caucasus. It is administratively part of the North Caucasian Federal District. Karachay-Cherkessia has a population of 469,865. Cherkessk is the largest city and the capital of the republic.

The Mountain Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic or Mountain ASSR was a short-lived autonomous republic within the Russian SFSR in the Northern Caucasus that existed from 20 January 1921, to 7 July 1924. The Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus was created from parts of the Kuban and Terek Oblasts by the indigenous nationalities after the Russian Revolution; however, Soviet rule was installed on this territory after the Red Army conquered the Northern Caucasus in the course of the Russian Civil War, and the former republic was transformed into a Soviet one. The area of the republic was over 73,000 square kilometres (28,000 sq mi), and the population was about 800,000. It comprised six okrugs: Balkar, Chechen, Kabardian, Karachay, Nazran (Ingushetia), and Vladikavkaz Okrug (Ossetia) and had two cities: Grozny and Vladikavkaz. In addition, a special autonomy was provided to the Terek Cossacks: Sunzha Cossack Okrug, which included a large enclave in northern Ingushetia, and a smaller one bordering Grozny. Its boundaries approximated those of classical Zyx.

The North Caucasus, or Ciscaucasia, is a mountainous region in Eastern Europe, governed by Russia. It constitutes the northern part of the wider Caucasus region, which forms the natural border between Europe and West Asia. It is bordered by the Sea of Azov and Black Sea to the west, the Caspian Sea to the east, and the Caucasus Mountains to the south. The region shares land borders with the South Caucasus countries of Georgia and Azerbaijan. Krasnodar is the largest city within the North Caucasus.

The Karachays or Karachai are an indigenous North Caucasian-Turkic ethnic group native to the North Caucasus. They are primarily located in their ancestral lands in Karachay–Cherkess Republic, a republic of Russia in the North Caucasus. They have a common origin, culture, and language with the Balkars.

Balkars are a Turkic ethnic group in the North Caucasus region, one of the titular populations of Kabardino-Balkaria.

Kabardino-Balkaria, officially the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic, is a republic of Russia located in the North Caucasus. As of the 2021 Census, its population was 904,200. Its capital is Nalchik. The area contains the highest mountain in Europe, Mount Elbrus, at 5,642 m (18,510 ft). Mount Elbrus has 22 glaciers that feed three rivers — Baksan, Malka and Kuban. The mountain is covered with snow year-round.

The Republic of Kabardino-Balkaria is a federal subject of Russia, located in the Caucasus region.

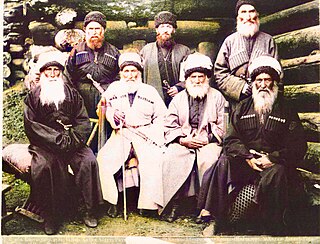

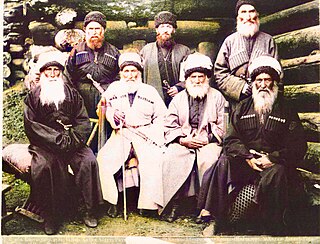

The peoples of the Caucasus, or Caucasians, are a diverse group comprising more than 50 ethnic groups throughout the Caucasus.

The United Vilayat of Kabarda-Balkaria-Karachay, also known as Vilayat KBK, was a militant Islamist Jihadist organization connected to numerous attacks against the local and federal security forces in the Russian republics of Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay-Cherkessia in the North Caucasus. Vilayet KBK has been a member of the Caucasus Emirate group since 2007.

The deportation of the Chechens and Ingush, or Ardakhar Genocide, and also known as Operation Lentil, was the Soviet forced transfer of the whole of the Vainakh populations of the North Caucasus to Central Asia on 23 February 1944, during World War II. The expulsion was ordered by NKVD chief Lavrentiy Beria after approval by Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, as a part of a Soviet forced settlement program and population transfer that affected several million members of ethnic minorities in the Soviet Union between the 1930s and the 1950s.

The flag of Karachay–Cherkessia, a federal subject and republic in the Russian Federation, was adopted on 26 July 1996.

Circassian nationalism is the desire among Circassians worldwide to preserve their culture, save their language from extinction, raise awareness about the Circassian genocide, return to Circassia and establish a completely autonomous or independent Circassian state in its pre-Russian invasion borders.

Amjad M. Jaimoukha was a Jordanian Circassian writer, publicist, and historian, who wrote several books on North Caucasian – specifically Circassian and Chechen – culture and folklore.

The National Anthem of Karachay-Cherkessia is the national anthem of the Karachay-Cherkess Republic, a federal subject of Russia in the North Caucasus. The lyrics were written by Yusuf Sozarukov (1952–2008), and the music was composed by Aslan Daurov (1940–1999). The anthem was adopted on 9 April 1998 by Law of the KChR number 410-XXII "On the State Anthem of the Republic of Karachay-Cherkessia". The title of the song is "Древней Родиной горжусь я!", meaning "Ancient Homeland I am proud of!".

The Kabardino-Balkarian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was an autonomous republic of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic within the Soviet Union, and was originally a part of the Mountain Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. On 16 January 1922 the region was detached from the Mountain ASSR and the Kabardino-Balkarian Autonomous Oblast on 1 September 1921. It became an autonomous republic on 5 December 1936. On 30 January 1991, the Kabardino-Balkarian ASSR declared state sovereignty. It is now the Kabardino-Balkaria republic, a federal subject of the Russian Federation. The Kabardino-Balkarian ASSR bordered no other sovereign states during the existence of the Soviet Union.

The Deportation of the Balkars was the expulsion by the Soviet government of the entire Balkar population of the North Caucasus to Central Asia on March 8, 1944, during World War II. The expulsion was ordered by NKVD chief Lavrentiy Beria after approval by Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin. All the 37,713 Balkars of the Caucasus were deported from their homeland in one day. The crime was a part of a Soviet forced settlement program and population transfer that affected several million members of non-Russian Soviet ethnic minorities between the 1930s and the 1950s. Officially the deportation was a response to the Balkars' supposed collaboration with occupying German forces. Later, in 1989, the Soviet government declared the deportation illegal.

The national emblem of the Kabardino-Balkarian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was adopted in 1937 by the government of the Kabardino-Balkarian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. The emblem is identical to the emblem of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.

The Deportation of the Karachays, codenamed Operation Seagull, was the Soviet government's forcible transfer of the entire Karachay population from the North Caucasus to Central Asia, mostly to the Kazakh and Kyrgyzstan SSRs, in November 1943, during World War II. The expulsion was ordered by NKVD chief Lavrentiy Beria, after it was approved by Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin. Nearly 70,000 Karachays of the Caucasus were deported from their native land. The crime was a part of a Soviet forced settlement program and population transfer that affected several million members of non-Russian Soviet ethnic minorities between the 1930s and the 1950s.

Musa Magomedovich Shanibov, born Yuri Mukhamedovich Shanibov and also known simply as Musa Shanib, was a Kabardian politician and terrorist who led the Confederation of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus from its founding until 1996. Shanibov led a largely-unsuccessful campaign for the region's nations to achieve independence from Russia and commanded volunteer troops in both the 1992–1993 War in Abkhazia. He was involved in the ethnic cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia.