Outpatient commitment—also called assisted outpatient treatment (AOT) or community treatment orders (CTO)—refers to a civil court procedure wherein a legal process orders an individual diagnosed with a severe mental disorder to adhere to an outpatient treatment plan designed to prevent further deterioration or recurrence that is harmful to themselves or others.

Psychiatric hospitals, also known as mental health hospitals or behavioral health hospitals, are hospitals or wards specializing in the treatment of severe mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, dissociative identity disorder, major depressive disorder and many others. Psychiatric hospitals vary widely in their size and grading. Some hospitals may specialize only in short-term or outpatient therapy for low-risk patients. Others may specialize in the temporary or permanent confinement of patients who need routine assistance, treatment, or a specialized and controlled environment due to a psychiatric disorder. Patients often choose voluntary commitment, but those whom psychiatrists believe to pose significant danger to themselves or others may be subject to involuntary commitment and involuntary treatment. Psychiatric hospitals may also be called psychiatric wards/units when they are a subunit of a regular hospital.

Anti-psychiatry, sometimes spelled antipsychiatry, is a movement based on the view that psychiatric treatment is often more damaging than helpful to patients, highlighting controversies about psychiatry. Objections include the reliability of psychiatric diagnosis, the questionable effectiveness and harm associated with psychiatric medications, the failure of psychiatry to demonstrate any disease treatment mechanism for psychiatric medication effects, and legal concerns about equal human rights and civil freedom being nullified by the presence of diagnosis. Historically critiques of psychiatry came to light after focus on the extreme harms associated with electroconvulsive treatment or insulin shock therapy. The term "anti-psychiatry" is in dispute and often used to dismiss all critics of psychiatry, many of who agree that a specialized role of helper for people in emotional distress may at times be appropriate, and allow for individual choice around treatment decisions.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or electroshock therapy (EST) is a psychiatric treatment where a generalized seizure is electrically induced to manage refractory mental disorders. Typically, 70 to 120 volts are applied externally to the patient's head, resulting in approximately 800 milliamperes of direct current passing between the electrodes, for a duration of 100 milliseconds to 6 seconds, either from temple to temple or from front to back of one side of the head. However, only about 1% of the electrical current crosses the bony skull into the brain because skull impedance is about 100 times higher than skin impedance.

Involuntary treatment refers to medical treatment undertaken without the consent of the person being treated. Involuntary treatment is permitted by law in some countries when overseen by the judiciary through court orders; other countries defer directly to the medical opinions of doctors.

Deinstitutionalisation is the process of replacing long-stay psychiatric hospitals with less isolated community mental health services for those diagnosed with a mental disorder or developmental disability. In the late 20th century, it led to the closure of many psychiatric hospitals, as patients were increasingly cared for at home, in halfway houses and clinics, in regular hospitals, or not at all.

The psychiatric survivors movement is a diverse association of individuals who either currently access mental health services, or who are survivors of interventions by psychiatry.

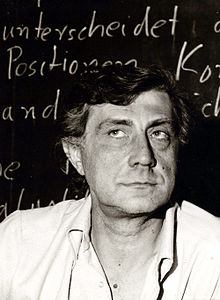

Franco Basaglia was an Italian psychiatrist, neurologist, professor who proposed the dismantling of psychiatric hospitals, pioneer of the modern concept of mental health, Italian psychiatry reformer, figurehead and founder of Democratic Psychiatry architect, and principal proponent of Law 180 which abolished mental hospitals in Italy. He is considered to be the most influential Italian psychiatrist of the 20th century.

Loren Richard Mosher was an American psychiatrist, clinical professor of psychiatry, expert on schizophrenia and the chief of the Center for Studies of Schizophrenia in the National Institute of Mental Health (1968–1980). Mosher spent his professional career advocating for humane and effective treatment for people diagnosed as having schizophrenia and was instrumental in developing an innovative, residential, home-like, non-hospital, non-drug treatment model for newly identified acutely psychotic persons.

Atascadero State Hospital, formally known as California Department of State Hospitals- Atascadero (DSHA), is located on the Central Coast of California, in San Luis Obispo County, halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco. DSHA is an all-male, maximum-security facility, forensic institution that houses mentally ill convicts who have been committed to psychiatric facilities by California's courts. Located on a 700+ acre grounds in the city of Atascadero, California, it is the largest employer in that town. DSHA is not a general purpose public hospital, and the only patients admitted are those that are referred to the hospital by the Superior Court, Board of Prison Terms, or the Department of Corrections.

Community mental health services (CMHS), also known as community mental health teams (CMHT) in the United Kingdom, support or treat people with mental disorders in a domiciliary setting, instead of a psychiatric hospital (asylum). The array of community mental health services vary depending on the country in which the services are provided. It refers to a system of care in which the patient's community, not a specific facility such as a hospital, is the primary provider of care for people with a mental illness. The goal of community mental health services often includes much more than simply providing outpatient psychiatric treatment.

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of deleterious mental conditions. These include various matters related to mood, behaviour, cognition, and perceptions.

The obligatory dangerousness criterion is a principle present in the mental health law of many developed countries. It mandates evidence of dangerousness to oneself or to others before involuntary treatment for mental illness. The term "dangerousness" refers to one's ability to hurt oneself or others physically or mentally within an imminent time frame, and the harm caused must have a long-term effect on the person(s).

Case management is the coordination of community-based services by a professional or team to provide quality mental health care customized accordingly to individual patients' setbacks or persistent challenges and aid them to their recovery. Case management seeks to reduce hospitalizations and support individuals' recovery through an approach that considers each person's overall biopsychosocial needs without making disadvantageous economic costs. As a result, care coordination includes traditional mental health services but may also encompass primary healthcare, housing, transportation, employment, social relationships, and community participation. In the 1940s, this was known as social counseling. It is the link between the client and care delivery system.

The lunatic asylum or insane asylum was an early precursor of the modern psychiatric hospital.

Democratic Psychiatry is Italian real society and movement for liberation of the ill and weak from segregation in mental hospitals by pushing for the Italian psychiatric reform. The movement was political in nature but not antipsychiatric in the sense in which this term is used in the Anglo-Saxon world. Democratic Psychiatry called for radical changes in the practice and theory of psychiatry and strongly attacked the way society managed mental illness. The movement was essential in the birth of the reform law of 1978.

Psychiatric reform in Italy is the reform of psychiatry which started in Italy after the passing of Basaglia Law in 1978 and terminated with the very end of the Italian state mental hospital system in 1998. Among European countries, Italy was the first to publicly declare its repugnance for a mental health care system which led to social exclusion and segregation. The psychiatric reform was also a consequence of a public debate sparked by Giorgio Coda's case and stories collected and analyzed in Alberto Papuzzi's book Portami su quello che canta.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to psychiatry:

The Experiences of an Asylum Doctor, with suggestions for asylum and lunacy law reform is a 1921 book written by British general practitioner Montagu Lomax (1860–1933). The book was an exposé of conditions within two English lunatic asylums based on Lomax's experiences as an Asylum medical officer between 1917 and 1919.