Related Research Articles

Involuntary commitment, civil commitment, involuntary hospitalization or involuntary hospitalisation, is a legal process through which an individual who is deemed by a qualified agent to have symptoms of severe mental disorder is detained in a psychiatric hospital (inpatient) where they can be treated involuntarily. This treatment may involve the administration of psychoactive drugs, including involuntary administration. In many jurisdictions, people diagnosed with mental health disorders can also be forced to undergo treatment while in the community; this is sometimes referred to as outpatient commitment and shares legal processes with commitment.

Outpatient commitment—also called assisted outpatient treatment (AOT) or community treatment orders (CTO)—refers to a civil court procedure wherein a legal process orders an individual diagnosed with a severe mental disorder to adhere to an outpatient treatment plan designed to prevent further deterioration or recurrence that is harmful to themselves or others.

Psychiatric hospitals, also known as mental health units or behavioral health units, are hospitals or wards specializing in the treatment of severe mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Psychiatric hospitals vary widely in their size and grading. Some hospitals may specialize only in short-term or outpatient therapy for low-risk patients. Others may specialize in the temporary or permanent containment of patients who need routine assistance, treatment, or a specialized and controlled environment due to a psychiatric disorder. Patients often choose voluntary commitment, but those whom psychiatrists believe to pose significant danger to themselves or others may be subject to involuntary commitment and involuntary treatment. Psychiatric hospitals may also be called psychiatric wards/units when they are a subunit of a regular hospital.

Anti-psychiatry is a movement based on the view that psychiatric treatment is often more damaging than helpful to patients, highlighting controversies about psychiatry. Objections may include concerns about the effectiveness and potential harm of treatments such as electroconvulsive treatment or insulin shock therapy.

Voluntary commitment is the act or practice of choosing to admit oneself to a psychiatric hospital, or other mental health facility. Unlike in involuntary commitment, the person is free to leave the hospital against medical advice, though there may be a requirement of a period of notice or that the leaving take place during daylight hours. In some jurisdictions, a distinction is drawn between formal and informal voluntary commitment, and this may have an effect on how much notice the individual must give before leaving the hospital. This period may be used for the hospital to use involuntary commitment procedures against the patient. People with mental illness can write psychiatric advance directives in which they can, in advance, consent to voluntary admission to a hospital and thus avoid involuntary commitment.

Castle Peak Hospital is the oldest psychiatric hospital in Hong Kong. Located at the east of Castle Peak in Tuen Mun, the hospital was established in 1961. Currently, it has 1,156 beds, providing a wide variety of psychiatric services such as adult psychiatry, forensic psychiatry, psychogeriatric services, child and adolescent psychiatry, consultation-liaison psychiatry and substance abuse treatments. All wards in the hospital are equipped to accommodate both voluntary and involuntary admitted patients.

Deinstitutionalisation is the process of replacing long-stay psychiatric hospitals with less isolated community mental health services for those diagnosed with a mental disorder or developmental disability. In the late 20th century, it led to the closure of many psychiatric hospitals, as patients were increasingly cared for at home, in halfway houses and clinics, in regular hospitals, or not at all.

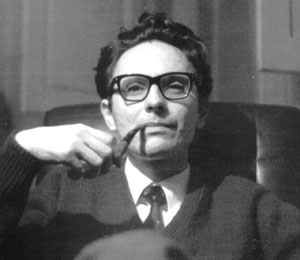

Franco Basaglia was an Italian psychiatrist, neurologist, professor who proposed the dismantling of psychiatric hospitals, pioneer of the modern concept of mental health, Italian psychiatry reformer, figurehead and founder of Democratic Psychiatry architect, and principal proponent of Law 180 which abolished mental hospitals in Italy. He is considered to be the most influential Italian psychiatrist of the 20th century.

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of mental disorders. These include various maladaptations related to mood, behaviour, cognition, and perceptions. See glossary of psychiatry.

The lunatic asylum was an early precursor of the modern psychiatric hospital.

Basaglia Law or Law 180 is the Italian Mental Health Act of 1978 which signified a large reform of the psychiatric system in Italy, contained directives for the closing down of all psychiatric hospitals and led to their gradual replacement with a whole range of community-based services, including settings for acute in-patient care. The Basaglia Law is the basis of Italian mental health legislation. The principal proponent of Law 180 and its architect was Italian psychiatrist Franco Basaglia. Therefore, Law 180 is known as the “Basaglia Law” from the name of its promoter. The Parliament of Italy approved the Law 180 on 13 May 1978, and thereby initiated the gradual dismantling of psychiatric hospitals. Implementation of the psychiatric reform law was accomplished in 1998 which marked the very end of the state psychiatric hospital system in Italy. The Law has had worldwide impact as other counties took up widely the Italian model. It was Democratic Psychiatry which was essential in the birth of the reform law of 1978.

Democratic Psychiatry is Italian real society and movement for liberation of the ill and weak from segregation in mental hospitals by pushing for the Italian psychiatric reform. The movement was political in nature but not antipsychiatric in the sense in which this term is used in the Anglo-Saxon world. Democratic Psychiatry called for radical changes in the practice and theory of psychiatry and strongly attacked the way society managed mental illness. The movement was essential in the birth of the reform law of 1978.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the psychiatric survivors movement:

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to psychiatry:

Giorgio Antonucci was an Italian physician, known for his questioning of the basis of psychiatry.

The anti-asylum movement or anti-asylum fight is an organized movement in Brazil consisting of psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers requesting a humanitarian improvement in psychiatrist public services. University campuses, hospitals and workers of the field promote events in order to raise awareness and fight discrimination against mental patients.

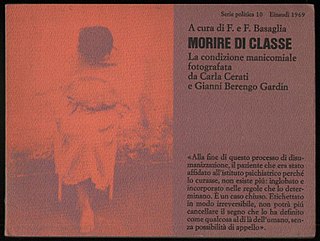

Morire di classe. La condizione manicomiale fotografata da Carla Cerati e Gianni Berengo Gardin, first published in 1969, is a polemical work about the conditions in Italian mental hospitals of the time, edited by Franco Basaglia and Franca Ongaro Basaglia and with black and white photographs by Carla Cerati and Gianni Berengo Gardin, an introduction by the Basaglias, and various other texts.

The United States has experienced two waves of deinstitutionalization, the process of replacing long-stay psychiatric hospitals with less isolated community mental health services for those diagnosed with a mental disorder or developmental disability.

Transinstitutionalisation is the phenomena where inmates released from one therapeutic community move into other institutions, either as planned move or as an unforeseen consequence. For instance, when the residential mental hospitals were closed as the result of a political policy change, the prison population increased by an equivalent number.

Giorgio Giuseppe Antonio Maria Coda is an Italian psychiatrist and professor. He was vicedirector of the mental hospital of Turin and director of villa Azzurra, in Grugliasco (Turin) After the trial, that lasted from 1970 to 1974, he was sentenced to five years of imprisonment for patient abuse, as well as to interdiction from the medical profession for five years and payment of legal expenses. He has been nicknamed "The Electrician" for his misuse of the electroshock therapy.

References

- ↑ Burti L. (2001). "Italian psychiatric reform 20 plus years after". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica . 104 (410 Supplementum): 41–46. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.1040s2041.x. PMID 11863050. S2CID 40910917.

- ↑ Ramon, Shulamit; Williams, Janet (2005). Mental health at the crossroads: the promise of the psychosocial approach. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7546-4191-9.

- 1 2 3 Tansella M. (November 1986). "Community psychiatry without mental hospitals — the Italian experience: a review". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine . 79 (11): 664–669. PMC 1290535 . PMID 3795212.

- ↑ "Dacia Maraini intervista Giorgio Antonucci" [Dacia Maraini interviews Giorgio Antonucci]. La Stampa (in Italian). 26 July, 29 and 30 December 1978. Archived from the original on 13 April 2013.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Del Giudice G. (1998). "Psychiatric Reform in Italy" (PDF). Trieste: Mental Health Department. Retrieved 5-10-2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - 1 2 "Dal 1968 al 1995: la prima fase del "superamento" dell'istituzione psichiatrica". Psichiatria e storia. Archived from the original on 2012-03-13. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

- 1 2 3 Russo G., Carelli F. (May 2009). "Dismantling asylums: The Italian Job" (PDF). London Journal of Primary Care.