New Ulm is a city in Brown County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 14,120 at the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Brown County. It is located on the triangle of land formed by the confluence of the Minnesota River and the Cottonwood River.

The Battle of Fort Ridgely was an early battle in the Dakota War of 1862. As the closest U.S. military post to the Lower Sioux Agency, the lightly fortified Fort Ridgely quickly became both a destination for refugees and a target of Dakota warbands after the attack at the Lower Sioux Agency. It came under attack by the Dakota on August 20, 1862, two days after a company of soldiers responding from the fort to the attack on the Lower Sioux Agency had been ambushed and defeated at the Battle of Redwood Ferry. The Dakota besieged and partially destroyed the fort, but were unable to storm it before the August 27 arrival of Colonel Henry Sibley with 1400 men from Fort Snelling prompted them to retreat.

Charles Eugene Flandrau was an American lawyer who became influential in the Minnesota Territory, and later state, after moving there in 1853 from New York City. He served on the Minnesota Territorial Council, in the Minnesota Constitutional Convention, and on the Minnesota territorial and state supreme courts. He was also an associate justice on the Minnesota Supreme Court.

Fort Ridgely was a frontier United States Army outpost from 1851 to 1867, built 1853–1854 in Minnesota Territory. The Sioux called it Esa Tonka. It was located overlooking the Minnesota river southwest of Fairfax, Minnesota. Half of the fort's land was part of the south reservation in the Minnesota river valley for the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute tribes. Fort Ridgely had no defensive wall, palisade, or guard towers. The Army referred to the fort as the "New Post on the Upper Minnesota" until it was named for three Maryland Army Officers named Ridgely, who died during the Mexican–American War.

The Battle of Redwood Ferry took place on August 18, 1862, on the first day of the Dakota War of 1862. A United States Army company responding to the Dakota attack at the Lower Sioux Agency from Fort Ridgeley was ambushed and defeated at Redwood Ferry.

The Battle of Whitestone Hill was the culmination of the 1863 operations against the Sioux or Dakota people in Dakota Territory. Brigadier General Alfred Sully attacked a village September 3–5, 1863. The Native Americans in the village included Yanktonai, Santee, and Teton (Lakota) Sioux. Sully killed, wounded, or captured 300 to 400 Sioux, including women and children, at a cost of about 60 casualties. Sully would continue the conflict with another campaign in 1864.

Big Eagle was the chief of a band of Mdewakanton Dakota in Minnesota. He played an important role as a military leader in the Dakota War of 1862. Big Eagle surrendered soon after the Battle of Wood Lake and was sentenced to death and imprisoned, but was pardoned by President Abraham Lincoln in 1864. Big Eagle's narrative, "A Sioux Story of the War" was first published in 1894, and is one of the most widely cited first-person accounts of the 1862 war in Minnesota from a Dakota point of view.

The 9th Minnesota Infantry Regiment was a Minnesota USV infantry regiment that served in the Union Army in the Western Theater of the American Civil War.

The 10th Minnesota Infantry Regiment was a Minnesota USV infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Fort Abercrombie, in North Dakota, was a United States Army fort established by authority of an Act of Congress, March 3, 1857. The act allocated twenty-five square miles of land on the Red River of the North in Dakota Territory to be used for a military outpost, but the exact location was left to the discretion of Lieutenant Colonel John J. Abercrombie. The fort was constructed in the year 1858. It was the first permanent military installation in what became North Dakota, and is thus known as "The Gateway to the Dakotas". Abercrombie selected a site right on the river. Spring flooding was a problem and the fort was abandoned. However, in 1860 the Army returned moving the fort to higher ground.

The Battle of Wood Lake occurred on September 23, 1862, and was the final battle in the Dakota War of 1862. The two-hour battle, which actually took place at nearby Lone Tree Lake, was a decisive victory for the U.S. forces led by Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley. With heavy casualties inflicted on the Dakota forces led by Chief Little Crow, the "hostile" Dakota warriors dispersed. Little Crow and 150 followers fled for the northern plains, while other Mdewakantons quietly joined the "friendly" Dakota camp started by the Sisseton and Wahpeton bands, which would soon become known as Camp Release.

The Battle of Birch Coulee occurred September 2–3, 1862 and resulted in the heaviest casualties suffered by U.S. forces during the Dakota War of 1862. The battle occurred after a group of Dakota warriors followed a U.S. burial expedition, including volunteer infantry, mounted guards and civilians, to an exposed plain where they were setting up camp. That night, 200 Dakota soldiers surrounded the camp and ambushed the Birch Coulee campsite in the early morning, commencing a siege that lasted for over 30 hours, until the arrival of reinforcements and artillery led by Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley.

The Attack at the Lower Sioux Agency was the first organized attack led by Dakota leader Little Crow in Minnesota on August 18, 1862, and is considered the initial engagement of the Dakota War of 1862. It resulted in 13 settler deaths, with seven more killed while fleeing the agency for Fort Ridgely.

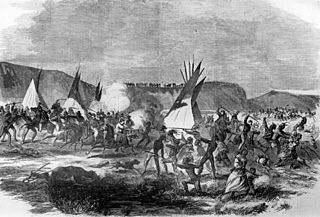

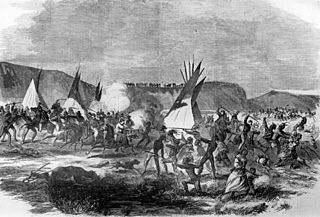

The Dakota War of 1862, also known as the Sioux Uprising, the Dakota Uprising, the Sioux Outbreak of 1862, the Dakota Conflict, or Little Crow's War, was an armed conflict between the United States and several eastern bands of Dakota collectively known as the Santee Sioux. It began on August 18, 1862, when the Dakota, who were facing starvation and displacement, attacked white settlements at the Lower Sioux Agency along the Minnesota River valley in southwest Minnesota. The war lasted for five weeks and resulted in the deaths of hundreds of settlers. In the aftermath, the Dakota people were exiled from their homelands, forcibly sent to reservations in the Dakotas and Nebraska, and the State of Minnesota confiscated and sold all their remaining land in the state. The war also ended with the largest mass execution in United States history with the hanging of 38 Dakota men.

The Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate of the Lake Traverse Reservation, formerly Sisseton-Wahpeton Sioux Tribe/Dakota Nation, is a federally recognized tribe comprising two bands and two subdivisions of the Isanti or Santee Dakota people. They are on the Lake Traverse Reservation in northeast South Dakota.

The 1st Dakota Cavalry was a Union battalion of two companies raised in the Dakota Territory during the American Civil War. They were deployed along the frontier, primarily to protect the settlers during the Sioux Uprising of 1862.

The Department of the Northwest was an U.S. Army Department created on September 6, 1862, to put down the Sioux uprising in Minnesota. Major General John Pope was made commander of the Department. At the end of the Civil War the Department was redesignated the Department of Dakota.

Acton is an unincorporated community in Acton Township, Meeker County, Minnesota, United States, near Grove City and Litchfield. The community is located along Meeker County Road 23 near State Highway 4. County Road 32 is also in the immediate area.

This timeline of South Dakota is a list of events in the history of South Dakota by year.

The Battle of Acton was a battle between the United States Army and Little Crow's band of Dakota warriors during the Dakota War of 1862. Following the defeats at Fort Ridgley and New Ulm, Chief Little Crow led an incursion north out of the Minnesota River Valley into central Minnesota. A detachment of the Tenth Minnesota Infantry Regiment commanded by Captain Richard Strout was sent to protect the citizens of Meeker County.