| Year | Translation and background | Genesis 1:1–3 | John (Johannes) 3:16 |

|---|

| 1271 | Rijmbijbel (Jacob van Maerlant) Catholic. Not a literal translation, but a poetic "history Bible" based on Petrus Comestor's Latin Historia scholastica | [God die maecte int beghin / Den hemel ende oec mede der in / Alle die inghelike nature / Desen hemel heet die scrifture / (...) ende hi maecte die erde mede / (...) Ende met deemstereden bedect / die scrifture die vertrect / dat die eleghe gheest ons heren / dats gods wille dus salment keeren / die wart up water ghedraghen / (...) DOe maecte god met sinen worde / dat lecht alse hict bescriuen hoerde /] | – |

| 1477 | Delftse Bijbel Catholic, based on the Latin Vulgate. First printed Dutch translation, Old Testament (excluding Psalms) only. | INden beghin sciep god hemel ende aerde. Mer die aerde was onnut ende ydel: ende donckerheden waren op die aensichten des afgronts. Ende goods gheest was ghedraghen bouen den wateren. Ende god seide dat licht moet werden: ende dat licht wort ghemaect [15] | – |

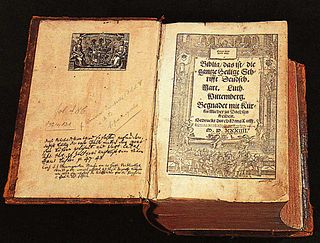

1526–

1542 | Liesveltbijbel Protestant (Lutheran). First fully printed Dutch Bible translation. NT based on Luther's 1522 September Bible (in turn based on Erasmus' 1519 Textus Receptus ); OT based on Luther's unfinished translation, the Latin Vulgate and other translations. Liesvelt was executed for his 'heretical' editions in 1545. [16] | [1542 edition] INden beginne schiep God hemel ende aerde, [1] ende dye aerde was woest ende leech, ende het was doncker opten afgront. Ende Gods geest dreef op den watere. Ende God sprack, Het worde licht, ende het werdt licht, [17] | † Alsoo heeft God die [11] werelt bemint, dat hi sinen eenighen sone gaf, op dat alle die in hem geloouen, nyet verloren en worden, mer dat eewich leuen hebben [18] |

1528–

1548 | Vorstermanbijbel Mixed version authorised by secular authorities. 1528 OT based on 1526 Liesveltbijbel, NT on Luther's 1522 September Bible. 1531 NT derived from Erasmian Textus Receptus. Later editions increasingly relied on Latin Vulgate until all Vorstermanbijbels were banned by the Catholic Church in 1548. | [1531 edition] INden beghinne schiep God * hemel ende aerde.) Ende die aerde was * ydel) ende ledich, ende die duysternissen waren opt aensicht des afgronts Ende Gods * gheest) dreef opt * watere.) Ende God sprack, Latet licht gemaect worden, Ende het licht wert gemaect, [19] | Want also heeft god die werelt bemint dat hi zijn eenige geboren soon gegeuen heeft op dat al die gene die in hem gelooft, nyet en vergae, mer hebbe dat eewighe leuen. [20] |

| 1548 | Leuvense Bijbel Catholic version authorised by the Catholic Church based on the Latin Vulgate to counter Textus Receptus-based Protestant translations. | INDEN beginne heeft Godt geschapen hemel ende aerde, maer die aerde was ydel ende ledich, ende die duysternissen waren op dat aenschijn des afgronts, ende den gheest Godts dreef op die wateren. Ende Godt heeft geseyt, Laet gemaect worden het licht. Ende het licht worde gemaect, | Want alsoe lief heeft Godt die werelt ghehadt dat hy sijnen eenighen sone ghegheuen heeft op dat alle die in hem ghelooft niet en vergae, maer hebbe dat eewich leuen. |

| 1560 | Biestkensbijbel Protestant (Baptist/Lutheran) version with strong similarities to a 1558 version published in Emden, which in turn was largely based on a 1554 High German Luther Bible printed in Magdeburg. Changes, references, emphases and notes point to Mennonite influence. [21] | INden beginne† schiep Godt Hemel ende Aerde. Ende de Aerde was woest ende ledich, ende het was duyster op der diepte, ende de Geest Gods* sweefde op den watere. † Ende God sprack: Het worde Licht. Ende het wert Licht, | * Alsoo lief heeft God de Werelt gehadt, dat hy sinen eenighen Soon gaf,† op dat alle die aen hem gheloouen, niet verloren en worden, maer dat eewich leuen hebben. |

| 1562 | Deux-Aesbijbel Calvinist translation during the Protestant Reformation, based on the 1526 (Lutheran) Liesveltbijbel and 1534 Luther Bible, which derived from the Textus Receptus. | IN dena beginne sciep God Hemel ende Aerde. Ende de Aerde was woest ende ledich, ende het was duyster op den afgront, ende de b geest Gods sweuede opt water. Ende God sprack: Het worde licht: ende het wert licht. | Want also lief heeft God de werelt gehadt, dat hy synen eenichgheboren Sone ghegheuen heeft, r op dat een yeghelick die in hem gelooft, [volgende kolom] niet verderue, maer het eewighe leuen hebbe: |

| 1637 | Statenvertaling (SV) Calvinist (de facto), authorised by the Dutch Republic government. Old Testament based on Masoretic Text, consulting the Septuagint. New Testament heavily dependent on the Textus Receptus, a Byzantine text-type. | In den beginne schiep God den hemel en de aarde. De aarde nu was woest en ledig, en duisternis was op den afgrond; en de Geest Gods zweefde op de wateren. En God zeide: Daar zij licht: en daar werd licht. | Want alzo lief heeft God de wereld gehad, dat Hij Zijn eniggeboren Zoon gegeven heeft, opdateen iegelijk die in Hem gelooft, niet verderve, maar het eeuwige leven hebbe. |

| 1648 | Visscherbijbel Lutheran translation derived from the Luther Bible, which used the Textus Receptus (a Byzantine text-type) for the New Testament. [12] | IN’t begin schiep Godt Hemel ende Aerde.[1] Ende de aerde was woest ende ledigh, ende het was duyster op de diepte, ende dea Geest Godts sweefde op ’t water. Ende Godt sprack: Het worde licht. Ende het wiert licht. [22] | ► Alsoo lief heeft Godt de Werelt gehadt, dat Hy sijnen eenigh-geborenen Soon gaf; op dat alle die in Hem gelooven, niet verloren en worden, maer het eeuwige leven hebben ←. [23] |

| 1951 | Nederlands Bijbelgenootschap 1951 (NBG 1951) Protestant interconfessional critical edition. Old Testament based on the Masoretic Text of Codex L, New Testament based primarily on the Alexandrian text-type. | In den beginne schiep God de hemel en de aarde. De aarde nu was woest en ledig, en duisternis lag op de vloed, en de Geest Gods zweefde over de wateren. En God zeide: Er zij licht; en er was licht. | Want alzo lief heeft God de wereld gehad, dat Hij zijn eniggeboren Zoon gegeven heeft, opdat een ieder, die in Hem gelooft, niet verloren ga, maar eeuwig leven hebbe. |

| 1969 | Nieuwe-Wereldvertaling van de Heilige Schrift (NW) Derived from the English Jehovah's Witnesses translation 1950–1961. First edition (using Westcott and Hort) was deemed unscholarly and theologically distorted; later editions (1970, 1984) were based on Nestle-Aland's text. | In [het] begin schiep God de hemel en de aarde. De aarde nu bleek vormloos en woest te zijn en er lag duisternis op het oppervlak van [de] waterdiepte; en Gods werkzame kracht bewoog zich heen en weer over de oppervlakte van de wateren. Nu zei God: „Er kome licht.” Toen kwam er licht. | Want God heeft de wereld zozeer liefgehad dat hij zijn eniggeboren Zoon heeft gegeven, opdat een ieder die geloof oefent in hem, niet vernietigd zou worden, maar eeuwig leven zou hebben. |

1975–

1995 | Willibrordvertaling (WV) Catholic translation | In het begin schiep God de hemel en de aarde. De aarde was woest en leeg; duisternis lag over de diepte, en de geest van God zweefde over de wateren. Toen zei God: ‘Er moet licht zijn!’ En er was licht. | Zoveel immers heeft God van de wereld gehouden, dat Hij zijn eniggeboren Zoon heeft geschonken, zodat iedereen die in Hem gelooft niet verloren gaat, maar eeuwig leven bezit. |

1983–

1996 | Groot Nieuws Bijbel (GNB) Ecumenic translation | In het begin schiep God de hemel en de aarde. De aarde was onherbergzaam en verlaten. Een watervloed bedekte haar en er heerste diepe duisternis. De wind van God joeg over het water. Toen zei God: ‘Er moet licht zijn!’ En er was licht. | Want God had de wereld zo lief dat hij zijn enige Zoon gegeven heeft, opdat iedereen die in hem gelooft, niet verloren gaat maar eeuwig leven heeft. |

| 1987 | Het Boek (HTB) Protestant edition in simple Dutch by the Dutch branch of the International Bible Society. | In het begin heeft God de hemelen en de aarde gemaakt. De aarde was woest en leeg en de Geest van God zweefde boven de watermassa. Over de watermassa lag een diepe duisternis. Toen zei God: "Laat er licht zijn." En toen was er licht. | Want God heeft zoveel liefde voor de wereld, dat Hij Zijn enige Zoon heeft gegeven; zodat ieder die in Hem gelooft, niet verloren gaat maar eeuwig leven heeft. |

| 2004 | Nieuwe Bijbelvertaling (NBV) Ecumenic critical edition. Old Testament based Masoretic Text (Codex L), Deuterocanonicals based on Göttinger Septuaginta 1931, New Testament based on the Alexandrian text-type (27th Nestle-Aland 2001). [24] | In het begin schiep God de hemel en de aarde. De aarde was nog woest en doods, en duisternis lag over de oervloed, maar Gods geest zweefde over het water. God zei: ‘Er moet licht komen,’ en er was licht. | Want God had de wereld zo lief dat hij zijn enige Zoon heeft gegeven, opdat iedereen die in hem gelooft niet verloren gaat, maar eeuwig leven heeft. |

| 2010 | Herziene Statenvertaling (HSV) Calvinist conservative Statenvertaling retranslation. Old Testament based on Masoretic Text, consulting the Septuagint and the Dead Sea Scrolls. New Testament heavily dependent on the Textus Receptus, a Byzantine text-type. [24] | In het begin schiep God de hemel en de aarde. De aarde nu was woest en leeg, en duisternis lag over de watervloed; en de Geest van God zweefde boven het water. En God zei: Laat er licht zijn! En er was licht. | Want zo lief heeft God de wereld gehad, dat Hij Zijn eniggeboren Zoon gegeven heeft, *opdat ieder die in Hem gelooft, niet verloren gaat, maar eeuwig leven heeft. |

| 2013 | BasisBijbel (BB) Protestant Statenvertaling retranslation by the Pocket Testament League. New Testament heavily dependent on the Textus Receptus, a Byzantine text-type. | In het begin maakte God de hemel en de aarde. De aarde was helemaal leeg. Er was nog niets. De aarde was bedekt met water en het was er helemaal donker. De Geest van God waaide over het diepe water. En God zei: "Ik wil dat er licht is!" Toen was er licht. | Want God houdt zoveel van de mensen, dat Hij zijn enige Zoon aan hen heeft gegeven. Iedereen die in Hem gelooft, zal niet verloren gaan, maar zal het eeuwige leven hebben. |

| 2014 | Bijbel in Gewone Taal (BGT) Protestant critical edition in simple/paraphased modern Dutch. New Testament based on the Alexandrian text-type (28th Nestle-Aland 2012). [24] | In het begin maakte God de hemel en de aarde. De aarde was leeg en verlaten. Overal was water, en alles was donker. En er waaide een hevige wind over het water. Toen zei God: ‘Er moet licht komen.’ En er kwam licht. | Want Gods liefde voor de mensen was zo groot, dat hij zijn enige Zoon gegeven heeft. Iedereen die in hem gelooft, zal niet sterven, maar voor altijd leven. |

|