A bicycle, also called a pedal cycle, bike, push-bike or cycle, is a human-powered or motor-assisted, pedal-driven, single-track vehicle, with two wheels attached to a frame, one behind the other. A bicycle rider is called a cyclist, or bicyclist.

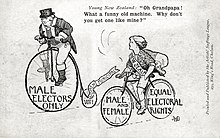

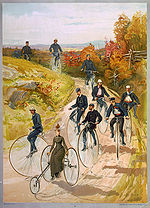

The penny-farthing, also known as a high wheel, high wheeler or ordinary, is an early type of bicycle. It was popular in the 1870s and 1880s, with its large front wheel providing high speeds, owing to it travelling a large distance for every rotation of the legs, and comfort, because the large wheel provided greater shock absorption.

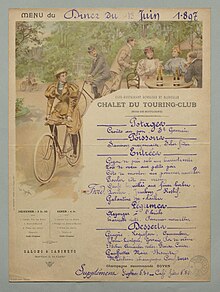

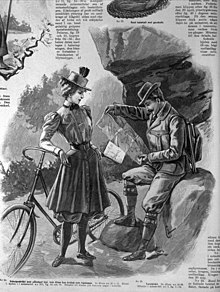

Bicycle touring is the taking of self-contained cycling trips for pleasure, adventure or autonomy rather than sport, commuting or exercise. Bicycle touring can range from single-day trips to extended travels spanning weeks or months. Tours may be planned by the participant or organized by a tourism business, local club or organization, or a charity as a fund-raising venture.

A utility bicycle, city bicycle, urban bicycle, European city bike (ECB), Dutch bike, classic bike or simply city-bike is a bicycle designed for frequent very short, relatively slow rides through very flat urban areas. It is a form of utility bicycle commonly seen around the world, built to facilitate everyday short-distance riding in normal clothes in cold-to-mild weather conditions. It is therefore a bicycle designed for very short-range practical transportation, as opposed to those primarily for recreation and competition, such as touring bicycles, road bicycles, and mountain bicycles. Utility bicycles are the most common form globally, and comprise the vast majority found in the developing world. City bikes may be individually owned or operated as part of a public bike sharing scheme.

A fixed-gear bicycle is a bicycle that has a drivetrain with no freewheel mechanism such that the pedals always will spin together with the rear wheel. The freewheel was developed early in the history of bicycle design but the fixed-gear bicycle remained the standard track racing design. More recently the "fixie" has become a popular alternative among mainly urban cyclists, offering the advantage of simplicity compared with the standard multi-geared bicycle.

Vehicles that have two wheels and require balancing by the rider date back to the early 19th century. The first means of transport making use of two wheels arranged consecutively, and thus the archetype of the bicycle, was the German draisine dating back to 1817. The term bicycle was coined in France in the 1860s, and the descriptive title "penny farthing", used to describe an "ordinary bicycle", is a 19th-century term.

Bicycle culture can refer to a mainstream culture that supports the use of bicycles or to a subculture. Although "bike culture" is often used to refer to various forms of associated fashion, it is erroneous to call fashion in and of itself a culture.

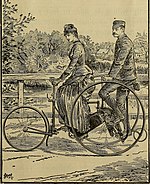

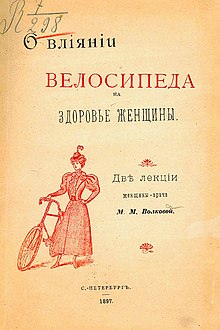

Fashion in the 1890s in Western countries is characterized by long elegant lines, tall collars, and the rise of sportswear. It was an era of great dress reforms led by the invention of the drop-frame safety bicycle, which allowed women the opportunity to ride bicycles more comfortably, and therefore, created the need for appropriate clothing.

Bloomers, also called the bloomer, the Turkish dress, the American dress, or simply reform dress, are divided women's garments for the lower body. They were developed in the 19th century as a healthful and comfortable alternative to the heavy, constricting dresses worn by American women. They take their name from their best-known advocate, the women's rights activist Amelia Bloomer.

Cycling shorts are short, skin-tight garments designed to improve comfort and efficiency while cycling.

Sterling Bicycle Co. was a 19th-century American bicycle company first based in Chicago, Illinois before relocating to Kenosha, Wisconsin.

A roadster bicycle is a type of utility bicycle once common worldwide, and still common in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and some parts of Europe. During the past few decades, traditionally styled roadster bicycles have regained popularity in the Western world, particularly as a lifestyle or fashion statement in an urban environment.

A step-through frame is a type of bicycle frame, often used for utility bicycles, with a low or absent top tube or cross-bar.

Annie Cohen Kopchovsky, known as Annie Londonderry, was a Jewish Latvian immigrant to the United States who in 1894–95 became the first woman to bicycle around the world. After having completed her travel, albeit mostly by ship, she built a media career around engagement with popular conception of what it was to be female.

Cycling quickly became an activity after bicycles were introduced in the 19th century and remains popular with more than a billion people worldwide used for recreation, transportation and sport.

Cycling is a popular mode of transport and leisure activity within London, the capital city of the United Kingdom. Following a national decline in the 1960s of levels of utility cycling, cycling as a mode of everyday transport within London began a slow regrowth in the 1970s. This continued until the beginning of the 21st century, when levels began to increase significantly—during the period from 2000 to 2012, the number of daily journeys made by bicycle in Greater London doubled to 580,000. The growth in cycling can partly be attributed to the launch in 2010 by Transport for London (TfL) of a cycle hire system throughout the city's centre. By 2013, the scheme was attracting a monthly ridership of approximately 500,000, peaking at a million rides in July of that year. Health impact analyses have shown that London would benefit more from increased cycling and cycling infrastructure than other European cities.

Detroit is a popular city for cycling. It is flat with an extensive road network with a number of recreational and competitive opportunities and is, according to cycling advocate David Byrne, one of the top eight biking cities in the world. The city has invested in greenways and bike lanes and other bicycle-friendly infrastructure. Bike rental is available from the riverfront and tours of the city's architecture can be booked.

Bicycling in Islam is a topic of discussion in Islam, primarily in regard to its use by Muslim women. Religious scholars are worried in particular about the effects of cycling on women's modesty and mobility.

Juliana Buhring is a British-German ultra-endurance cyclist and writer. In December 2012, she set the first Guinness World Record as the fastest woman to circumnavigate the globe by bike, riding over 29,000 kilometres (18,000 mi) in a total time of 152 days.

Mrs Sarah Maddock (1860–1955) was an Australian endurance cyclist during the 1890s and early 1900s and the first woman to ride a bicycle from Sydney to Melbourne and later Sydney to Brisbane and back.