Related Research Articles

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums. In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to vote is called active suffrage, as distinct from passive suffrage, which is the right to stand for election. The combination of active and passive suffrage is sometimes called full suffrage.

Universal suffrage ensures the right to vote for as many people who are bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the "one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion of youth and non-citizens, while some insist that much more inclusion is needed before suffrage can be called universal. Democratic theorists, especially those hoping to achieve more universal suffrage, support presumptive inclusion, where the legal system would protect the voting rights of all subjects unless the government can clearly prove that disenfranchisement is necessary. Universal full suffrage includes both the right to vote and be a candidate.

The American Anti-Slavery Society was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave, had become a prominent abolitionist and was a key leader of this society, who often spoke at its meetings. William Wells Brown, also a freedman, also often spoke at meetings. By 1838, the society had 1,350 local chapters with around 250,000 members.

Voting rights, specifically enfranchisement and disenfranchisement of different groups, has been a moral and political issue throughout United States history.

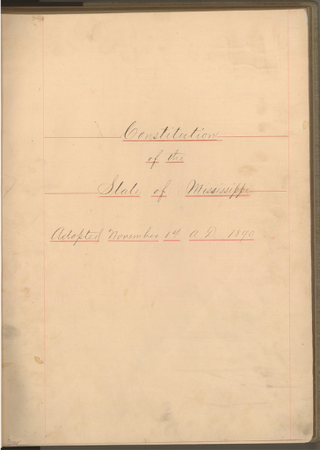

The Constitution of Mississippi is the primary organizing law for the U.S. state of Mississippi delineating the duties, powers, structures, and functions of the state government. Mississippi's original constitution was adopted at a constitutional convention held at Washington, Mississippi in advance of the western portion of the territory's admission to the Union in 1817. The current state constitution was adopted in 1890 following the reconstruction period. It has been amended and updated 100 times in since its adoption in 1890, with some sections being changed or repealed altogether. The most recent modification to the constitution occurred in November 2020, when Section 140 was amended, and Sections 141-143 were repealed.

Women's suffrage, or the right to vote, was established in the United States over the course of more than half a century, first in various states and localities, sometimes on a limited basis, and then nationally in 1920 with the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution.

The first Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women was held in New York City on May 9–12, 1837, to discuss the American abolition movement. This gathering represented the first time that women from such a broad geographic area met with the common purpose of promoting the anti-slavery cause among women, and it also was likely the first major convention where women discussed women's rights. Some prominent women went on to be vocal members of the Women's Suffrage Movement, including Lucretia Mott, the Grimké sisters, and Lydia Maria Child. After the first convention in 1837, there were also conventions in 1838 and 1839

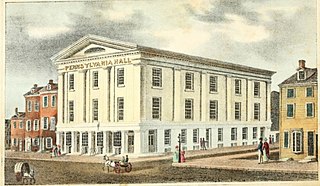

Pennsylvania Hall, "one of the most commodious and splendid buildings in the city," was an abolitionist venue in Philadelphia, built in 1837–38. It was a "Temple of Free Discussion", where antislavery, women's rights, and other reform lecturers could be heard. Four days after it opened it was destroyed by arson, the work of an anti-abolitionist mob.

Black suffrage refers to black people's right to vote and has long been an issue in countries established under conditions of black minorities as well as, in some cases black majorities.

The lily-white movement was an anti-black political movement within the Republican Party in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a response to the political and socioeconomic gains made by African-Americans following the Civil War and the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which eliminated slavery and involuntary servitude "except as punishment for a crime".

Lucretia Mott was an American Quaker, abolitionist, women's rights activist, and social reformer. She had formed the idea of reforming the position of women in society when she was amongst the women excluded from the World Anti-Slavery Convention held in London in 1840. In 1848, she was invited by Jane Hunt to a meeting that led to the first public gathering about women's rights, the Seneca Falls Convention, during which the Declaration of Sentiments was written.

The American Equal Rights Association (AERA) was formed in 1866 in the United States. According to its constitution, its purpose was "to secure Equal Rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color or sex." Some of the more prominent reform activists of that time were members, including women and men, blacks and whites.

African-American women began to agitate for political rights in the 1830s, creating the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, and New York Female Anti-Slavery Society. These interracial groups were radical expressions of women's political ideals, and they led directly to voting rights activism before and after the Civil War. Throughout the 19th century, African-American women such as Harriet Forten Purvis, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper worked on two fronts simultaneously: reminding African-American men and white women that Black women needed legal rights, especially the right to vote.

John C. Bowers was an African American entrepreneur, organist and vestryman at St. Thomas African Episcopal Church, and a founding member of the first Grand United Order of Odd Fellows for African Americans in Pennsylvania. He was active in the anti-slavery movement in Philadelphia, and involved in the founding of several organizations including the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. "A fervent abolitionist and outspoken opponent of colonization, [he] was much in demand as a public speaker."

In the United States, a person may have their voting rights suspended or withdrawn due to the conviction of a criminal offense. The actual class of crimes that results in disenfranchisement vary between jurisdictions, but most commonly classed as felonies, or may be based on a certain period of incarceration or other penalty. In some jurisdictions disfranchisement is permanent, while in others suffrage is restored after a person has served a sentence, or completed parole or probation. Felony disenfranchisement is one among the collateral consequences of criminal conviction and the loss of rights due to conviction for criminal offense. In 2016, 6.1 million individuals were disenfranchised on account of a conviction, 2.47% of voting-age citizens. As of October 2020, it was estimated that 5.1 million voting-age US citizens were disenfranchised for the 2020 presidential election on account of a felony conviction, 1 in 44 citizens. As suffrage rights are generally bestowed by state law, state felony disenfranchisement laws also apply to elections to federal offices.

The Ohio Women's Convention at Salem in 1850 met on April 19–20, 1850 in Salem, Ohio, a center for reform activity. It was the third in a series of women's rights conventions that began with the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848. It was the first of these conventions to be organized on a statewide basis. About five hundred people attended. All of the convention's officers were women. Men were not allowed to vote, sit on the platform or speak during the convention. The convention sent a memorial to the convention that was preparing a new Ohio state constitution, asking it to provide for women's right to vote.

This is a timeline of voting rights in the United States, documenting when various groups in the country gained the right to vote or were disenfranchised.

William H. Yates was an African-American abolitionist, writer, and the President of the first Convention of Colored Men. He focused his writing in the form of articles and editorials in newspapers; along with responses about books and articles written on slavery or civil rights.

African Americans were fully enfranchised in practice throughout the United States by the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Prior to the Civil War and the Reconstruction Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, some Black people in the United States had the right to vote, but this right was often abridged or taken away. After 1870, Black people were theoretically equal before the law, but in the period between the end of Reconstruction era and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 this was frequently infringed in practice.

Alfred Niger was a free Black activist who lived in Providence, Rhode Island and worked as a barber. Niger was a leading influential figure in the movement for Black suffrage in early 19th century Rhode Island, during the onset of the Dorr Rebellion.

References

- ↑ Wood, Nicholas (2011). "'A Sacrifice on the Altar of Slavery': Doughface Politics and Black Disenfranchisement in Pennsylvania, 1837–1838". Journal of the Early Republic . 31 (1): 75–106.

- ↑ John Agg; Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention (1837). Proceedings and debates of the Convention of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania : to propose amendments to the Constitution, commenced and held at Harrisburg, on the second day of May, 1837. Harrisburg: Packer, Barrett and Parke. pp. 29–106. OCLC 155867701.

- ↑ Yates, William. Rights of Coloured Men to Suffrage Citizenship and Trial by Jury. Philadelphia: Merrihew and Gunn. Carters Alley. 1838.

- ↑ Purvis, Robert, Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens, Threatened with Disfranchisement, to the People of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: 1838)

- ↑ Willard Sterne Randall, Forgotten Americans (1998) pg 166

- ↑ Webb, Samuel. History of Pennsylvania Hall Which Was Destroyed by a Mob: Merrihew and Gunn. Carter’s Alley. 1838