Related Research Articles

Anubis or Inpu, Anpu in Ancient Egyptian is the Greek name of the god of death, mummification, embalming, the afterlife, cemeteries, tombs, and the Underworld, in ancient Egyptian religion, usually depicted as a canine or a man with a canine head. Archeologists have identified Anubis's sacred animal as an Egyptian canid, the African golden wolf. The African wolf was formerly called the "African golden jackal", until a 2015 genetic analysis updated the taxonomy and the common name for the species. As a result, Anubis is often referred to as having a "jackal" head, but this "jackal" is now more properly called a "wolf".

Osiris is the god of fertility, agriculture, the afterlife, the dead, resurrection, life, and vegetation in ancient Egyptian religion. He was classically depicted as a green-skinned deity with a pharaoh's beard, partially mummy-wrapped at the legs, wearing a distinctive atef crown, and holding a symbolic crook and flail. He was one of the first to be associated with the mummy wrap. When his brother, Set, cut him up into pieces after killing him, Isis, his wife, found all the pieces and wrapped his body up, enabling him to return to life. Osiris was at times considered the eldest son of the earth god Geb and the sky goddess Nut, as well as being brother and husband of Isis, with Horus being considered his posthumously begotten son. He was also associated with the epithet Khenti-Amentiu, meaning "Foremost of the Westerners", a reference to his kingship in the land of the dead. Through syncretism with Iah, he is also a god of the Moon.

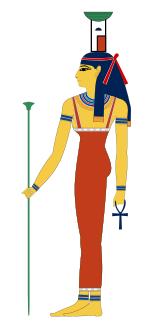

Isis was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingdom as one of the main characters of the Osiris myth, in which she resurrects her slain husband, the divine king Osiris, and produces and protects his heir, Horus. She was believed to help the dead enter the afterlife as she had helped Osiris, and she was considered the divine mother of the pharaoh, who was likened to Horus. Her maternal aid was invoked in healing spells to benefit ordinary people. Originally, she played a limited role in royal rituals and temple rites, although she was more prominent in funerary practices and magical texts. She was usually portrayed in art as a human woman wearing a throne-like hieroglyph on her head. During the New Kingdom, as she took on traits that originally belonged to Hathor, the preeminent goddess of earlier times, Isis was portrayed wearing Hathor's headdress: a sun disk between the horns of a cow.

Hapi, sometimes transliterated as Hapy, is one of the four sons of Horus in ancient Egyptian religion, depicted in funerary literature as protecting the throne of Osiris in the Underworld. Hapi was the son of Heru-ur and Isis or Serqet. He is not to be confused with another god of the same name. He is commonly depicted with the head of a hamadryas baboon, and is tasked with protecting the lungs of the deceased, hence the common depiction of a hamadryas baboon head sculpted as the lid of the canopic jar that held the lungs. Hapi is in turn protected by the goddess Nephthys. When his image appears on the side of a coffin, he is usually aligned with the side intended to face north. When embalming practices changed during the Third Intermediate Period and the mummified organs were placed back inside the body, an amulet of Hapi would be included in the body cavity.

The Osiris myth is the most elaborate and influential story in ancient Egyptian mythology. It concerns the murder of the god Osiris, a primeval king of Egypt, and its consequences. Osiris's murderer, his brother Set, usurps his throne. Meanwhile, Osiris's wife Isis restores her husband's body, allowing him to posthumously conceive their son, Horus. The remainder of the story focuses on Horus, the product of the union of Isis and Osiris, who is at first a vulnerable child protected by his mother and then becomes Set's rival for the throne. Their often violent conflict ends with Horus's triumph, which restores Maat to Egypt after Set's unrighteous reign and completes the process of Osiris's resurrection.

Nut, also known by various other transcriptions, is the goddess of the sky, stars, cosmos, mothers, astronomy, and the universe in the ancient Egyptian religion. She was seen as a star-covered nude woman arching over the Earth, or as a cow. She was depicted wearing the water-pot sign (nw) that identifies her.

Nephthys or Nebet-Het in ancient Egyptian was a goddess in ancient Egyptian religion. A member of the Great Ennead of Heliopolis in Egyptian mythology, she was a daughter of Nut and Geb. Nephthys was typically paired with her sister Isis in funerary rites because of their role as protectors of the mummy and the god Osiris and as the sister-wife of Set.

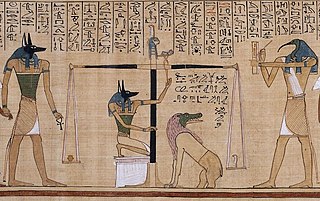

Maat or Maʽat refers to the ancient Egyptian concepts of truth, balance, order, harmony, law, morality, and justice. Maat was also the goddess who personified these concepts, and regulated the stars, seasons, and the actions of mortals and the deities who had brought order from chaos at the moment of creation. Her ideological opposite was Isfet, meaning injustice, chaos, violence or to do evil.

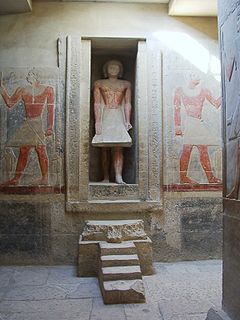

Duat is the realm of the dead in ancient Egyptian mythology. It has been represented in hieroglyphs as a star-in-circle: 𓇽. The god Osiris was believed to be the lord of the underworld. He was the first mummy as depicted in the Osiris myth and he personified rebirth and life after death. The underworld was also the residence of various other gods along with Osiris. The Duat was the region through which the sun god Ra traveled from west to east each night, and it was where he battled Apophis, who embodied the primordial chaos which the sun had to defeat in order to rise each morning and bring order back to the earth. It was also the place where people's souls went after death for judgment, though that was not the full extent of the afterlife. Burial chambers formed touching-points between the mundane world and the Duat, and the ꜣḫ "the effectiveness of the dead", could use tombs to travel back and forth from the Duat.

The ancient Egyptians believed that a soul was made up of many parts. In addition to these components of the soul, there was the human body.

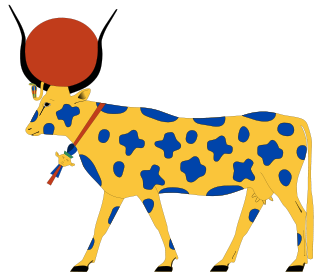

Hesat is an ancient Egyptian goddess in the form of a cow. She was said to provide humanity with milk and in particular to suckle the pharaoh and several ancient Egyptian bull gods. In the Pyramid Texts she is said to be the mother of Anubis and of the deceased king. She was especially connected with Mnevis, the living bull god worshipped at Heliopolis, and the mothers of Mnevis bulls were buried in a cemetery dedicated to Hesat. In Ptolemaic times she was closely linked with the goddess Isis.

The Book of the Dead is an ancient Egyptian funerary text generally written on papyrus and used from the beginning of the New Kingdom to around 50 BCE. The original Egyptian name for the text, transliterated rw nw prt m hrw, is translated as Book of Coming Forth by Day or Book of Emerging Forth into the Light. "Book" is the closest term to describe the loose collection of texts consisting of a number of magic spells intended to assist a dead person's journey through the Duat, or underworld, and into the afterlife and written by many priests over a period of about 1,000 years.

The Eye of Horus, wedjat eye or udjat eye is a concept and symbol in ancient Egyptian religion that represents well-being, healing, and protection. It derives from the mythical conflict between the god Horus with his rival Set, in which Set tore out or destroyed one or both of Horus's eyes and the eye was subsequently healed or returned to Horus with the assistance of another deity, such as Thoth. Horus subsequently offered the eye to his deceased father Osiris, and its revivifying power sustained Osiris in the afterlife. The Eye of Horus was thus equated with funerary offerings as well as with all the offerings given to deities in temple ritual. It could also represent other concepts, such as the Moon, whose perceived waxing and waning was likened to the injury and restoration of the eye.

The Pyramid Texts are the oldest ancient Egyptian funerary texts, dating to the late Old Kingdom. They are the earliest known corpus of ancient Egyptian religious texts. Written in Old Egyptian, the pyramid texts were carved onto the subterranean walls and sarcophagi of pyramids at Saqqara from the end of the Fifth Dynasty, and throughout the Sixth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom, and into the Eighth Dynasty of the First Intermediate Period.

The four sons of Horus were a group of four gods in ancient Egyptian religion, who were essentially the personifications of the four canopic jars, which accompanied mummified bodies. Since the heart was thought to embody the soul, it was left inside the body. The brain was thought only to be the origin of mucus, so it was reduced to liquid, removed with metal hooks, and discarded. This left the stomach, liver, large intestines, and lungs, which were removed, embalmed and stored, each organ in its own jar. There were times when embalmers deviated from this scheme: during the 21st Dynasty they embalmed and wrapped the viscera and returned them to the body, while the canopic jars remained empty symbols.

The Book of the Dead of Nehem-es-Rataui is, along with the Papyrus Brocklehurst, the most important papyrus in the collection of the Museum August Kestner in Hanover. It contains one of the many traditional versions of the Egyptian Book of the Dead, which differs most significantly from similar papyri in the style of the central scene of the Judgement of the dead.

Ancient Egyptian afterlife beliefs were centered around a variety of complex rituals that were influenced by many aspects of Egyptian culture. Religion was a major contributor, since it was an important social practice that bound all Egyptians together. For instance, many of the Egyptian gods played roles in guiding the souls of the dead through the afterlife. With the evolution of writing, religious ideals were recorded and quickly spread throughout the Egyptian community. The solidification and commencement of these doctrines were formed in the creation of afterlife texts which illustrated and explained what the dead would need to know in order to complete the journey safely.

The Assessors of Maat were 42 minor ancient Egyptian deities of the Maat charged with judging the souls of the dead in the afterlife by joining the judgment of Osiris in the Weighing of the Heart.

References

- ↑ , Rijksmuseum van Oudheden homepage. Search "dodenboek" in Collectie → Collectiezoeker to obtain sample images.

- ↑ van Dijk 1995, p. 7

- ↑ van Dijk 1995, p. 8

- ↑ van Dijk 1995, p. 8

- ↑ van Dijk 1995, p. 8. Verbatim, except to render Egyptian xtxt in author's accompanying hieroglyphic transcript, his “prevented” is replaced by “stopped”)

- ↑ Kemp 2007, p. 66

- ↑ Von Dassow 1998, plate 33

- ↑ Von Dassow 1998, plate 33

- ↑ Taylor 2001, p. 197

- ↑ 'Taylor 2001, p. 20

- ↑ Smith 2009, p. 3

- ↑ Von Dassow 1998, plate 33

- ↑ Taylor 2001, p. 54

- ↑ Taylor 2001, pp. 65-66

- ↑ Allen 2010, Answer to Exercise 16.33, p. 485

- ↑ Faulkner 1968, p 40

- ↑ Bunson 2009, p. 132.

- ↑ Irmtraut Munro in University College, London. 2002. Digital Egypt for Universities, Book of the Dead. [website]. http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/literature/religious/bdbynumber.html

- ↑ Bunson 2009, p. 89.

- ↑ Kemp 2007, pp. 4, 16.

- ↑ Zabkar 1968, p. 110.

- ↑ Shaw 2000, pp. 122, 209-210, 266-267.

- ↑ University of Bonn. n.d. Däs Altägyptische Totenbuch, object record TM 134346 [website] http://totenbuch.awk.nrw.de/objekt/tm134346

- ↑ van Dijk 1995, pp. 9-10

- ↑ Kemp 2007, pp. 56-57

- ↑ Kemp 2007, p. 68

- ↑ Taylor 2001, pp. 200, 205-208

- ↑ van Dijk 1995, pp. 10-11