The Battle of Fort Dearborn was an engagement between United States troops and Potawatomi Native Americans that occurred on August 15, 1812, near Fort Dearborn in what is now Chicago, Illinois. The battle, which occurred during the War of 1812, followed the evacuation of the fort as ordered by the commander of the United States Army of the Northwest, William Hull. The battle lasted about 15 minutes and resulted in a complete victory for the Native Americans. After the battle, Fort Dearborn was burned down. Some of the soldiers and settlers who had been taken captive were later ransomed.

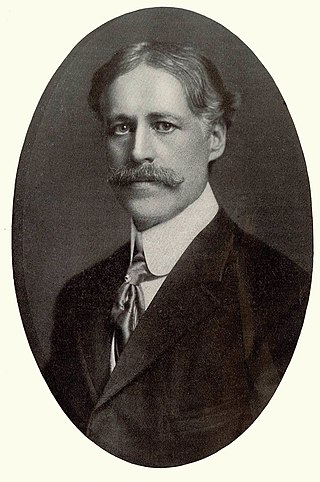

Daniel Chester French was an American sculptor of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He is best known for his 1874 sculpture The Minute Man in Concord, Massachusetts, and his 1920 monumental statue of Abraham Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.

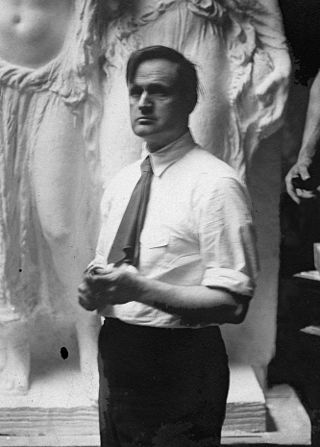

Frederick William MacMonnies was the best known expatriate American sculptor of the Beaux-Arts school, as successful and lauded in France as he was in the United States. He was also a highly accomplished painter and portraitist. He was born in Brooklyn Heights, Brooklyn, New York and died in New York City.

Karl Theodore Francis Bitter was an Austrian-born American sculptor best known for his architectural sculpture, memorials and residential work.

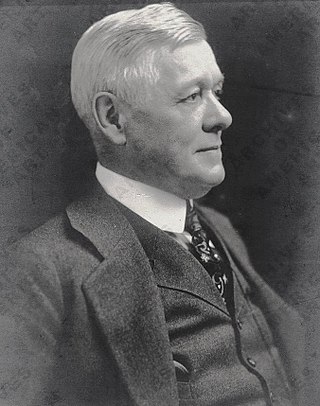

William Ordway Partridge was an American sculptor, teacher and author. Among his best-known works are the Shakespeare Monument in Chicago, the equestrian statue of General Grant in Brooklyn, the Pietà at St. Patrick's Cathedral in Manhattan, and the Pocahontas statue in Jamestown, Virginia.

James Earle Fraser was an American sculptor during the first half of the 20th century. His work is integral to many of Washington, D.C.'s most iconic structures.

There are many outdoor sculptures in Washington, D.C. In addition to the capital's most famous monuments and memorials, many figures recognized as national heroes have been posthumously awarded with his or her own statue in a park or public square. Some figures appear on several statues: Abraham Lincoln, for example, has at least three likenesses, including those at the Lincoln Memorial, in Lincoln Park, and the old Superior Court of the District of Columbia. A number of international figures, such as Mohandas Gandhi, have also been immortalized with statues. The Statue of Freedom is a 19½-foot tall allegorical statue that rests atop the United States Capitol dome.

Charles Henry Niehaus was an American sculptor.

Bela Lyon Pratt was an American sculptor from Connecticut.

Nellie Verne Walker, was an American sculptor best known for her statue of James Harlan formerly in the National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol, Washington D.C.

John Massey Rhind was a Scottish-American sculptor. Among Rhind's better known works is the marble statue of Dr. Crawford W. Long located in the National Statuary Hall Collection in Washington D.C. (1926).

Sigvald Asbjørnsen was a Norwegian-born American sculptor.

General Philip Sheridan is a bronze sculpture that honors Civil War general Philip Sheridan. The monument was sculpted by Gutzon Borglum, best known for his design of Mount Rushmore. Dedicated in 1908, dignitaries in attendance at the unveiling ceremony included President Theodore Roosevelt, members of the President's cabinet, high-ranking military officers and veterans from the Civil War and Spanish–American War. The equestrian statue is located in the center of Sheridan Circle in the Sheridan-Kalorama neighborhood of Washington, D.C. The bronze statue, surrounded by a plaza and park, is one of eighteen Civil War monuments in Washington, D.C., which were collectively listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. The sculpture and surrounding park are owned and maintained by the National Park Service, a federal agency of the Interior Department.

The General William Tecumseh Sherman Monument is an equestrian statue of American Civil War Major General William Tecumseh Sherman located in Sherman Plaza, which is part of President's Park in Washington, D.C., in the United States. The selection of an artist in 1896 to design the monument was highly controversial. During the monument's design phase, artist Carl Rohl-Smith died, and his memorial was finished by a number of other sculptors. The Sherman statue was unveiled in 1903. It is a contributing property to the Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C. and to the President's Park South, both of which are historic sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

John J. Boyle was an American sculptor active in Philadelphia in the last decades of the 19th century, known for his large-scale figurative bronzes in public settings, and, particularly, his portraiture of Native Americans.

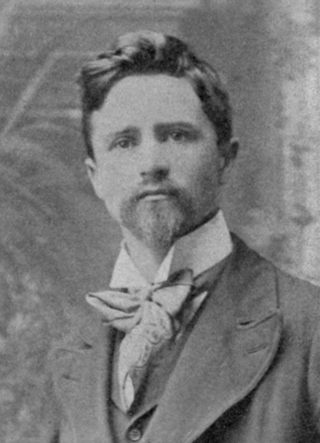

Johannes Sophus Gelert (1852–1923) was a Danish-born sculptor, who came to the United States in 1887 and during a span of more than thirty years produced numerous works of civic art in the Midwest and on the East Coast.

The Lafayette dollar was a silver coin issued as part of the United States' participation in the Paris World's Fair of 1900. Depicting Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette with George Washington, and designed by Chief Engraver Charles E. Barber, it was the only U.S. silver dollar commemorative prior to 1983, and the first U.S. coin to depict American citizens.

The Fort Dearborn Massacre Monument, also known as Potawatomi Rescue and Black Partidge Saving Mrs. Helm, is an 1893 bronze sculpture by Carl Rohl-Smith (1848–1900) that was installed in Chicago, in the U.S. state of Illinois. The statue is about nine feet in height. It depicts Black Partridge, a Potawatomi chief, saving the life of Margaret Helm, the wife of a U.S. army officer, during the Battle of Fort Dearborn in 1812.