Fortified wine is a wine to which a distilled spirit, usually brandy, has been added. In the course of some centuries, winemakers have developed many different styles of fortified wine, including port, sherry, madeira, Marsala, Commandaria wine, and the aromatised wine vermouth.

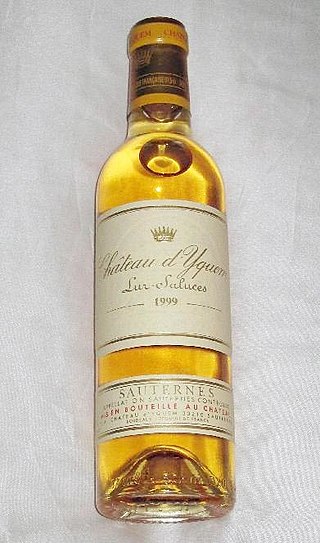

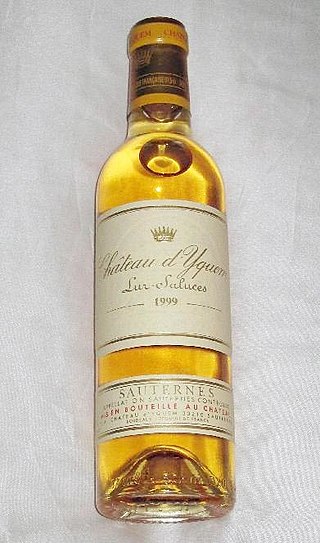

Dessert wines, sometimes called pudding wines in the United Kingdom, are sweet wines typically served with dessert.

Winemaking, wine-making, or vinification is the production of wine, starting with the selection of the fruit, its fermentation into alcohol, and the bottling of the finished liquid. The history of wine-making stretches over millennia. There is evidence that suggests that the earliest wine production took place in Georgia and Iran around 6000 to 5000 B.C. The science of wine and winemaking is known as oenology. A winemaker may also be called a vintner. The growing of grapes is viticulture and there are many varieties of grapes.

Fruit wines are fermented alcoholic beverages made from a variety of base ingredients ; they may also have additional flavors taken from fruits, flowers, and herbs. This definition is sometimes broadened to include any alcoholic fermented beverage except beer. For historical reasons, mead, cider, and perry are also excluded from the definition of fruit wine.

Viognier is a white wine grape variety. It is the only permitted grape for the French wine Condrieu in the Rhône Valley.

Carbonic maceration is a winemaking technique, often associated with the French wine region of Beaujolais, in which whole grapes are fermented in a carbon dioxide rich environment before crushing. Conventional alcoholic fermentation involves crushing the grapes to free the juice and pulp from the skin with yeast serving to convert sugar into ethanol. Carbonic maceration ferments most of the juice while it is still inside the grape, although grapes at the bottom of the vessel are crushed by gravity and undergo conventional fermentation. The resulting wine is fruity with very low tannins. It is ready to drink quickly but lacks the structure for long-term aging. In extreme cases such as Beaujolais nouveau, the period between picking and bottling can be less than six weeks.

A rosé is a type of wine that incorporates some of the color from the grape skins, but not enough to qualify it as a red wine. It may be the oldest known type of wine, as it is the most straightforward to make with the skin contact method. The pink color can range from a pale "onionskin" orange to a vivid near-purple, depending on the grape varieties used and winemaking techniques. Usually, the wine is labelled rosé in French, Portuguese, and English-speaking countries, rosado in Spanish, or rosato in Italian.

The subjective sweetness of a wine is determined by the interaction of several factors, including the amount of sugar in the wine, but also the relative levels of alcohol, acids, and tannins. Sugars and alcohol enhance a wine's sweetness, while acids cause sourness and bitter tannins cause bitterness. These principles are outlined in the 1987 work by Émile Peynaud, The Taste of Wine.

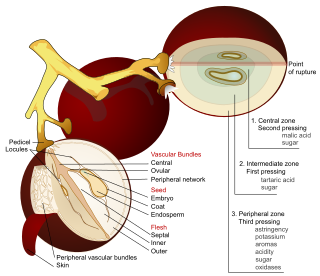

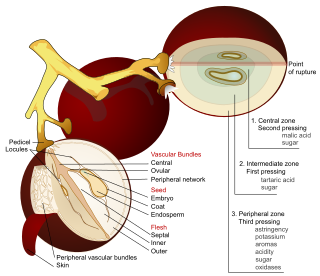

Maceration is the winemaking process where the phenolic materials of the grape—tannins, coloring agents (anthocyanins) and flavor compounds—are leached from the grape skins, seeds and stems into the must. To macerate is to soften by soaking, and maceration is the process by which the red wine receives its red color, since raw grape juice is clear-grayish in color. In the production of white wines, maceration is either avoided or allowed only in very limited manner in the form of a short amount of skin contact with the juice prior to pressing. This is more common in the production of varietals with less natural flavor and body structure like Sauvignon blanc and Sémillon. For Rosé, red wine grapes are allowed some maceration between the skins and must, but not to the extent of red wine production.

Jura wine is French wine produced in the Jura département. Located between Burgundy and Switzerland, this cool climate wine region produces wines with some similarity to Burgundy and Swiss wine. Jura wines are distinctive and unusual wines, the most famous being vin jaune, which is made by a similar process to Sherry, developing under a flor-like strain of yeast. This is made from the local Savagnin grape variety. Other grape varieties include Poulsard, Trousseau, and Chardonnay. Other wine styles found in Jura includes a vin de paille made from Chardonnay, Poulsard and Savagnin, a sparkling Crémant du Jura made from slightly unripe Chardonnay grapes, and a vin de liqueur known as Macvin du Jura made by adding marc to halt fermentation. The renowned French chemist and biologist Louis Pasteur was born and raised in the Jura region and owned a vineyard near Arbois.

Wine fraud relates to the commercial aspects of wine. The most prevalent type of fraud is one where wines are adulterated, usually with the addition of cheaper products and sometimes with harmful chemicals and sweeteners.

Languedoc-Roussillon wine, including the vin de pays labeled Vin de Pays d'Oc, is produced in southern France. While "Languedoc" can refer to a specific historic region of France and Northern Catalonia, usage since the 20th century has primarily referred to the northern part of the Languedoc-Roussillon region of France, an area which spans the Mediterranean coastline from the French border with Spain to the region of Provence. The area has around 700,000 acres (2,800 km2) under vines and is the single biggest wine-producing region in the world, being responsible for more than a third of France's total wine production. In 2001, the region produced more wine than the United States.

The process of fermentation in winemaking turns grape juice into an alcoholic beverage. During fermentation, yeasts transform sugars present in the juice into ethanol and carbon dioxide. In winemaking, the temperature and speed of fermentation are important considerations as well as the levels of oxygen present in the must at the start of the fermentation. The risk of stuck fermentation and the development of several wine faults can also occur during this stage, which can last anywhere from 5 to 14 days for primary fermentation and potentially another 5 to 10 days for a secondary fermentation. Fermentation may be done in stainless steel tanks, which is common with many white wines like Riesling, in an open wooden vat, inside a wine barrel and inside the wine bottle itself as in the production of many sparkling wines.

A vin de liqueur (French) or mistela (Spanish) is a sweet fortified style of French wine and Spanish wine that is fortified with brandy to unfermented grape must. The term vin de liqueur is also used by the European Union to refer to all fortified wines.

Marsannay wine is produced in the communes of Marsannay-la-Côte, Couchey and Chenôve in the Côte de Nuits subregion of Burgundy. The Appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) Marsannay may be used for red and rosé wine with Pinot noir, as well as white wine with Chardonnay as the main grape variety. Red wine accounts for the largest part of the production, around two-thirds. Marsannay is the only village-level appellation which may produce rosé wines, under the designation Marsannay rosé. All other Burgundy rosés are restricted to the regional appellation Bourgogne. There are no Grand Cru or Premier Cru vineyards in Marsannay. The Marsannay AOC was created in 1987, and is the most recent addition to the Côte de Nuits.

Sugars in wine are at the heart of what makes winemaking possible. During the process of fermentation, sugars from wine grapes are broken down and converted by yeast into alcohol (ethanol) and carbon dioxide. Grapes accumulate sugars as they grow on the grapevine through the translocation of sucrose molecules that are produced by photosynthesis from the leaves. During ripening the sucrose molecules are hydrolyzed (separated) by the enzyme invertase into glucose and fructose. By the time of harvest, between 15 and 25% of the grape will be composed of simple sugars. Both glucose and fructose are six-carbon sugars but three-, four-, five- and seven-carbon sugars are also present in the grape. Not all sugars are fermentable, with sugars like the five-carbon arabinose, rhamnose and xylose still being present in the wine after fermentation. Very high sugar content will effectively kill the yeast once a certain (high) alcohol content is reached. For these reasons, no wine is ever fermented completely "dry". Sugar's role in dictating the final alcohol content of the wine sometimes encourages winemakers to add sugar during winemaking in a process known as chaptalization solely in order to boost the alcohol content – chaptalization does not increase the sweetness of a wine.

The acids in wine are an important component in both winemaking and the finished product of wine. They are present in both grapes and wine, having direct influences on the color, balance and taste of the wine as well as the growth and vitality of yeast during fermentation and protecting the wine from bacteria. The measure of the amount of acidity in wine is known as the “titratable acidity” or “total acidity”, which refers to the test that yields the total of all acids present, while strength of acidity is measured according to pH, with most wines having a pH between 2.9 and 3.9. Generally, the lower the pH, the higher the acidity in the wine. There is no direct connection between total acidity and pH. In wine tasting, the term “acidity” refers to the fresh, tart and sour attributes of the wine which are evaluated in relation to how well the acidity balances out the sweetness and bitter components of the wine such as tannins. Three primary acids are found in wine grapes: tartaric, malic, and citric acids. During the course of winemaking and in the finished wines, acetic, butyric, lactic, and succinic acids can play significant roles. Most of the acids involved with wine are fixed acids with the notable exception of acetic acid, mostly found in vinegar, which is volatile and can contribute to the wine fault known as volatile acidity. Sometimes, additional acids, such as ascorbic, sorbic and sulfurous acids, are used in winemaking.

This glossary of winemaking terms lists some of terms and definitions involved in making wine, fruit wine, and mead.

In viticulture, ripeness is the completion of the ripening process of wine grapes on the vine which signals the beginning of harvest. What exactly constitutes ripeness will vary depending on what style of wine is being produced and what the winemaker and viticulturist personally believe constitutes ripeness. Once the grapes are harvested, the physical and chemical components of the grape which will influence a wine's quality are essentially set so determining the optimal moment of ripeness for harvest may be considered the most crucial decision in winemaking.

The role of yeast in winemaking is the most important element that distinguishes wine from fruit juice. In the absence of oxygen, yeast converts the sugars of the fruit into alcohol and carbon dioxide through the process of fermentation. The more sugars in the grapes, the higher the potential alcohol level of the wine if the yeast are allowed to carry out fermentation to dryness. Sometimes winemakers will stop fermentation early in order to leave some residual sugars and sweetness in the wine such as with dessert wines. This can be achieved by dropping fermentation temperatures to the point where the yeast are inactive, sterile filtering the wine to remove the yeast or fortification with brandy or neutral spirits to kill off the yeast cells. If fermentation is unintentionally stopped, such as when the yeasts become exhausted of available nutrients and the wine has not yet reached dryness, this is considered a stuck fermentation.