Related Research Articles

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency whose mandate is to advance social and economic justice by setting international labour standards. Founded in October 1919 under the League of Nations, it is one of the first and oldest specialised agencies of the UN. The ILO has 187 member states: 186 out of 193 UN member states plus the Cook Islands. It is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, with around 40 field offices around the world, and employs some 3,381 staff across 107 nations, of whom 1,698 work in technical cooperation programmes and projects.

Debt bondage, also known as debt slavery, bonded labour, or peonage, is the pledge of a person's services as security for the repayment for a debt or other obligation. Where the terms of the repayment are not clearly or reasonably stated, or where the debt is excessively large the person who holds the debt has thus some control over the laborer, whose freedom depends on the undefined or excessive debt repayment. The services required to repay the debt may be undefined, and the services' duration may be undefined, thus allowing the person supposedly owed the debt to demand services indefinitely. Debt bondage can be passed on from generation to generation.

Child labour is the exploitation of children through any form of work that interferes with their ability to attend regular school, or is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such exploitation is prohibited by legislation worldwide, although these laws do not consider all work by children as child labour; exceptions include work by child artists, family duties, supervised training, and some forms of work undertaken by Amish children, as well as by Indigenous children in the Americas.

The Harkin–Engel Protocol, sometimes referred to as the Cocoa Protocol, is an international agreement aimed at ending the worst forms of child labor and forced labor in the production of cocoa, the main ingredient in chocolate. The protocol was negotiated by U.S. Senator Tom Harkin and U.S. Representative Eliot Engel in response to a documentary and multiple articles in 2000 and 2001 reporting widespread child slavery and child trafficking in the production of cocoa. The protocol was signed in September 2001. Joint Statements in 2001, 2005 and 2008 and a Joint Declaration in 2010 extended the commitment to address the problem.

Child labour in Botswana is defined as the exploitation of children through any form of work which is harmful to their physical, mental, social and moral development. Child labour in Botswana is characterised by the type of forced work at an associated age, as a result of reasons such as poverty and household-resource allocations. Child labour in Botswana is not of higher percentage according to studies. The United States Department of Labor states that due to the gaps in the national frameworks, scarce economy, and lack of initiatives, “children in Botswana engage in the worst forms of child labour”. The International Labour Organization is a body of the United Nations which engages to develop labour policies and promote social justice issues. The International Labour Organization (ILO) in convention 138 states the minimum required age for employment to act as the method for "effective abolition of child labour" through establishing minimum age requirements and policies for countries when ratified. Botswana ratified the Minimum Age Convention in 1995, establishing a national policy allowing children at least fourteen-years old to work in specified conditions. Botswana further ratified the ILO's Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, convention 182, in 2000.

Child labour in Eswatini is a controversial issue that affects a large portion of the country's population. Child labour is often seen as a human rights concern because it is "work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development," as defined by the International Labour Organization (ILO). Additionally, child labour is harmful in that it restricts a child's ability to attend school or receive an education. The ILO recognizes that not all forms of children working are harmful, but this article will focus on the type of child labour that is generally accepted as harmful to the child involved.

Technically speaking, Paraguayan law prohibits discrimination on grounds of gender, race, language, disability, or social status, but there is nonetheless widespread discrimination.

A talibé is a boy, usually from Senegal, the Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Chad, Mali or Mauritania, who studies the Quran at a daara. This education is guided by a teacher known as a marabout. In most cases talibés leave their parents to stay in the daara.

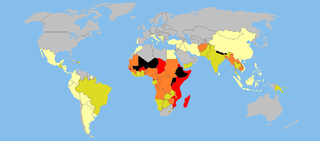

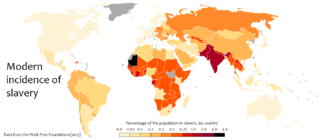

Contemporary slavery, also sometimes known as modern slavery or neo-slavery, refers to institutional slavery that continues to occur in present-day society. Estimates of the number of enslaved people today range from around 38 million to 49.6 million, depending on the method used to form the estimate and the definition of slavery being used. The estimated number of enslaved people is debated, as there is no universally agreed definition of modern slavery; those in slavery are often difficult to identify, and adequate statistics are often not available.

Uzbekistan is a source country for women and girls who are trafficked to the United Arab Emirates (U.A.E.), Kazakhstan, Russia, Thailand, Turkey, India, Indonesia, Israel, Malaysia, South Korea, Japan and Costa Rica for the purpose of commercial sexual exploitation. Men are trafficked to Kazakhstan and Russia for purposes of forced labor in the construction, cotton and tobacco industries. Men and women are also trafficked internally for the purposes of domestic servitude, forced labor in the agricultural and construction industries, and for commercial sexual exploitation. Many school-age children are forced to work in the cotton harvest each year.

A significant proportion of children in India are engaged in child labour. In 2011, the national census of India found that the total number of child labourers, aged [5–14], to be at 10.12 million, out of the total of 259.64 million children in that age group. The child labour problem is not unique to India; worldwide, about 217 million children work, many full-time.

Child labour in Pakistan is the employment of children to work in Pakistan, which causes them mental, physical, moral and social harm. Child labour takes away the education from children. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan estimated that in the 1990s, 11 million children were working in the country, half of whom were under age ten. In 1996, the median age for a child entering the work force was seven, down from eight in 1994. It was estimated that one quarter of the country's work force was made up of children. Child labor stands out as a significant issue in Pakistan, primarily driven by poverty. The prevalence of poverty in the country has compelled children to engage in labor, as it has become necessary for their families to meet their desired household income level, enabling them to afford basic necessities like butter and bread.

Human trafficking is a major and complex societal issue in Myanmar, which is both a source and destination for human trafficking. Both major forms of human trafficking, namely forced labor and forced prostitution, are common in the country, affecting men, women, and children. Myanmar's systemic political and economic problems have made the Burmese people particularly vulnerable to trafficking. Men, women, and children who migrate abroad to Thailand, Malaysia, China, Bangladesh, India, and South Korea for work are often trafficked into conditions of forced or bonded labor or commercial sexual exploitation. Economic conditions within Myanmar have led to the increased legal and illegal migration of citizens regionally and internationally, often to destinations as far from Myanmar as the Middle East. As of July 2022, Myanmar remained on the lowest tier of countries in the Trafficking in Persons Report. The border regions of Myanmar, including Shwe Kokko, are known human trafficking destinations.

Child labour refers to the full-time employment of children under a minimum legal age. In 2003, an International Labour Organization (ILO) survey reported that one in every ten children in the capital above the age of seven was engaged in child domestic labour. Children who are too young to work in the fields work as scavengers. They spend their days rummaging in dumps looking for items that can be sold for money. Children also often work in the garment and textile industry, in prostitution, and in the military.

Debt bondage in India or Bandhua Mazdoori was legally abolished in 1976 but remains prevalent due to weak enforcement by the government. Bonded labour is a system in which lenders force their borrowers to repay loans through labor. Additionally, these debts often take a large amount of time to pay off and are unreasonably high, propagating a cycle of generational inequality. This is due to the typically high interest rates on the loans given out by employers. Although debt bondage is considered to be a voluntary form of labor, people are forced into this system by social situations.

Child labour in Africa is generally defined based on two factors: type of work and minimum appropriate age of the work. If a child is involved in an activity that is harmful to his/her physical and mental development, he/she is generally considered as a child labourer. That is, any work that is mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful to children, and interferes with their schooling by depriving them of the opportunity to attend school or requiring them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work. Appropriate minimum age for each work depends on the effects of the work on the physical health and mental development of children. ILO Convention No. 138 suggests the following minimum age for admission to employment under which, if a child works, he/she is considered as a child laborer: 18 years old for hazardous works, and 13–15 years old for light works, although 12–14 years old may be permitted for light works under strict conditions in very poor countries. Another definition proposed by ILO's Statistical Information and Monitoring Program on Child Labor (SIMPOC) defines a child as a child labourer if he/she is involved in an economic activity, and is under 12 years old and works one or more hours per week, or is 14 years old or under and works at least 14 hours per week, or is 14 years old or under and works at least one hour per week in activities that are hazardous, or is 17 or under and works in an "unconditional worst form of child labor".

Cotton production in Uzbekistan is important to the national economy of the country. It is Uzbekistan's main cash crop, accounting for 17% of its exports in 2006. With annual cotton production of about 1 million ton of fiber and exports of 700,000-800,000 tons, Uzbekistan is the 8th largest producer and the 11th largest exporter of cotton in the world. Cotton's nickname in Uzbekistan is "white gold".

Labour rights in Azerbaijan are substantially constrained. Labor rights activists face repression in Azerbaijan. Azerbaijani law nominally allows the formation of labor unions and the right to strike, but in practice, most unions collaborate with the authoritarian regime, many categories of workers are prohibited from striking, and most major industries are dominated by state-owned enterprises where the government sets working conditions.

Elena Urlaeva is an Uzbek human rights activist. She is the president of the Human Rights Alliance of Uzbekistan. She focuses on "document[ing] the practice of forced labour in the cotton industry." According to the BBC, "Urlaeva's persistent work contributed to an international campaign which ultimately led major global brands to join a boycott of Uzbek cotton."

Xinjiang is the leading producer of cotton in China, accounting for about 20% of the world's cotton production and 80% of China's domestic cotton production. Critics of the industry's practices have alleged widespread human rights abuses, prompting global boycotts. China rejects accusations that any human rights abuses occur either within the Xinjiang cotton industry or within China overall.

References

- ↑ "Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor - Uzbekistan". US Department of Labor – Bureau of International Labor Affairs. Retrieved April 6, 2024.

- ↑ "Uzbek cotton is free from systemic child labour and forced labour". www.ilo.org. 2022-03-01. Retrieved 2024-04-06.

- ↑ "Child labour and the High Street". BBC. 30 October 2007.

- ↑ Gulnoza Saidazimova (19 January 2008). "Uzbekistan: Cotton industry targeted by child-labor activists". Radio Free Europe.

- ↑ Nick Mathiason (24 May 2009). "Uzbekistan forced to stop child labour". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Uzbekistan's cotton industry rebounds after boycott". euronews. 2023-12-18. Retrieved 2024-04-06.

- 1 2 "Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor - Uzbekistan". www.dol.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-03-17. Retrieved 2015-12-28.

- ↑ "Uzbekistan: Widespread child labor persists away from the fields". Eurasianet.org. January 30, 2023. Retrieved April 6, 2024.