The economy of Cambodia currently follows an open market system and has seen rapid economic progress in the last decade. Cambodia had a GDP of $28.54 billion in 2022. Per capita income, although rapidly increasing, is low compared with most neighboring countries. Cambodia's two largest industries are textiles and tourism, while agricultural activities remain the main source of income for many Cambodians living in rural areas. The service sector is heavily concentrated on trading activities and catering-related services. Recently, Cambodia has reported that oil and natural gas reserves have been found off-shore.

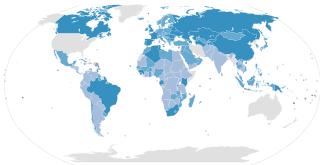

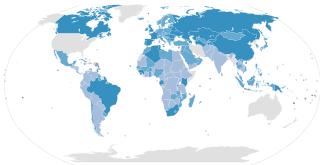

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency whose mandate is to advance social and economic justice by setting international labour standards. Founded in October 1919 under the League of Nations, it is one of the first and oldest specialised agencies of the UN. The ILO has 187 member states: 186 out of 193 UN member states plus the Cook Islands. It is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, with around 40 field offices around the world, and employs some 3,381 staff across 107 nations, of whom 1,698 work in technical cooperation programmes and projects.

Child labour is the exploitation of children through any form of work that deprives them of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, or is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such exploitation is prohibited by legislation worldwide, although these laws do not consider all work by children as child labour; exceptions include work by child artists, family duties, supervised training, and some forms of work undertaken by Amish children, as well as by Indigenous children in the Americas.

Child prostitution is prostitution involving a child, and it is a form of commercial sexual exploitation of children. The term normally refers to prostitution of a minor, or person under the legal age of consent. In most jurisdictions, child prostitution is illegal as part of general prohibition on prostitution.

Labor rights or workers' rights are both legal rights and human rights relating to labor relations between workers and employers. These rights are codified in national and international labor and employment law. In general, these rights influence working conditions in the relations of employment. One of the most prominent is the right to freedom of association, otherwise known as the right to organize. Workers organized in trade unions exercise the right to collective bargaining to improve working conditions.

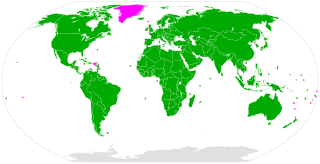

The Convention Concerning the Prohibition and Immediate Action for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labour, known in short as the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, was adopted by the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 1999 as ILO Convention No 182. It is one of eight ILO fundamental conventions.

Commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) is a commercial transaction that involves the sexual exploitation of a minor, or person under the age of consent. CSEC involves a range of abuses, including but not limited to: the, child pornography, stripping, erotic massage, phone sex lines, internet-based exploitation, and early forced marriage.

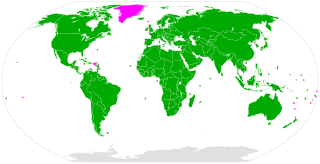

The ILO Convention Concerning Minimum Age for Admission to Employment C138, is a convention adopted in 1973 by the International Labour Organization. It requires ratifying states to pursue a national policy designed to ensure the effective abolition of child labour and to raise progressively the minimum age for admission to employment or work. It is one of eight ILO fundamental conventions. Convention C138 replaces several similar ILO conventions in specific fields of labour.

Child labour in Botswana is defined as the exploitation of children through any form of work which is harmful to their physical, mental, social and moral development. Child labour in Botswana is characterised by the type of forced work at an associated age, as a result of reasons such as poverty and household-resource allocations. child labour in Botswana is not of higher percentage according to studies. The United States Department of Labor states that due to the gaps in the national frameworks, scarce economy, and lack of initiatives, “children in Botswana engage in the worst forms of child labour”. The International Labour Organization is a body of the United Nations which engages to develop labour policies and promote social justice issues. The International Labour Organization (ILO) in convention 138 states the minimum required age for employment to act as the method for "effective abolition of child labour" through establishing minimum age requirements and policies for countries when ratified. Botswana ratified the Minimum Age Convention in 1995, establishing a national policy allowing children at least fourteen-years old to work in specified conditions. Botswana further ratified the ILO's Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, convention 182, in 2000.

Child labour in Eswatini is a controversial issue that affects a large portion of the country's population. Child labour is often seen as a human rights concern because it is "work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development," as defined by the International Labour Organization (ILO). Additionally, child labour is harmful in that it restricts a child's ability to attend school or receive an education. The ILO recognizes that not all forms of children working are harmful, but this article will focus on the type of child labour that is generally accepted as harmful to the child involved.

Child labour in Namibia is not always reported. This involved cases of child prostitution as well as voluntary and forced agricultural labour, cattle herding and vending.

Forced prostitution, also known as involuntary prostitution or compulsory prostitution, is prostitution or sexual slavery that takes place as a result of coercion by a third party. The terms "forced prostitution" or "enforced prostitution" appear in international and humanitarian conventions, such as the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, but have been inconsistently applied. "Forced prostitution" refers to conditions of control over a person who is coerced by another to engage in sexual activity.

Child labour in Bangladesh is significant, with 4.7 million children aged 5 to 14 in the work force in 2002-03. Out of the child labourers engaged in the work force, 83% are employed in rural areas and 17% are employed in urban areas. Child labour can be found in agriculture, poultry breeding, fish processing, the garment sector and the leather industry, as well as in shoe production. Children are involved in jute processing, the production of candles, soap and furniture. They work in the salt industry, the production of asbestos, bitumen, tiles and ship breaking.

Thailand is a centre for child sex tourism and child prostitution. Even though domestic and international authorities work to protect children from sexual abuse, the problem still persists in Thailand and many other Southeast Asian countries. Child prostitution, like other forms of child sexual abuse, not only causes death and high morbidity rates in millions of children but also violates their rights and dignity.

Child labour in Africa is generally defined based on two factors: type of work and minimum appropriate age of the work. If a child is involved in an activity that is harmful to his/her physical and mental development, he/she is generally considered as a child labourer. That is, any work that is mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful to children, and interferes with their schooling by depriving them of the opportunity to attend school or requiring them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work. Appropriate minimum age for each work depends on the effects of the work on the physical health and mental development of children. ILO Convention No. 138 suggests the following minimum age for admission to employment under which, if a child works, he/she is considered as a child laborer: 18 years old for hazardous works, and 13–15 years old for light works, although 12–14 years old may be permitted for light works under strict conditions in very poor countries. Another definition proposed by ILO's Statistical Information and Monitoring Program on Child Labor (SIMPOC) defines a child as a child labourer if he/she is involved in an economic activity, and is under 12 years old and works one or more hours per week, or is 14 years old or under and works at least 14 hours per week, or is 14 years old or under and works at least one hour per week in activities that are hazardous, or is 17 or under and works in an "unconditional worst form of child labor".

Child labor in the Philippines is the employment of children in hazardous occupations below the age of fifteen (15), or without the proper conditions and requirements below the age of fifteen (15), where children are compelled to work on a regular basis to earn a living for themselves and their families, and as a result are disadvantaged educationally and socially. So to make it short, it is called child labor when it is forced.

International labour law is the body of rules spanning public and private international law which concern the rights and duties of employees, employers, trade unions and governments in regulating Work and the workplace. The International Labour Organization and the World Trade Organization have been the main international bodies involved in reforming labour markets. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have indirectly driven changes in labour policy by demanding structural adjustment conditions for receiving loans or grants. Issues regarding Conflict of laws arise, determined by national courts, when people work in more than one country, and supra-national bodies, particularly in the law of the European Union, have a growing body of rules regarding labour rights.

Child labour laws are statutes placing restrictions and regulations on the work of minors.

Child labor in Bolivia is a widespread phenomenon. A 2014 document on the worst forms of child labor released by the U.S. Department of Labor estimated that approximately 20.2% of children between the ages of 7 and 14, or 388,541 children make up the labor force in Bolivia. Indigenous children are more likely to be engaged in labor than children who reside in urban areas. The activities of child laborers are diverse, however the majority of child laborers are involved in agricultural labor, and this activity varies between urban and rural areas. Bolivia has ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1990. Bolivia has also ratified the International Labour Organization’s Minimum Age Convention, 1973 (138) and the ILO’s worst forms of child labor convention (182). In July 2014, the Bolivian government passed the new child and adolescent code, which lowered the minimum working age to ten years old given certain working conditions The new code stipulates that children between the ages of ten and twelve can legally work given they are self-employed while children between 12 and 14 may work as contracted laborers as long as their work does not interfere with their education and they work under parental supervision.

Child labor, the practice of employing children under the legal age set by a government, is considered one of Brazil's most significant social issues. According to data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), more than 2.7 million minors between the ages of 5 and 17 worked in the country in 2015; 79,000 were between the ages of 5 and 9. Under Brazilian law, 16 is the minimum age to enter the labor market and 14 is the minimum age to work as an apprentice.