This article needs additional citations for verification .(October 2023) |

| Chlamydia psittaci | |

|---|---|

| |

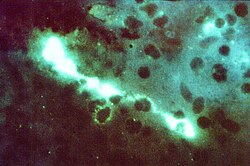

| Direct fluorescent antibody stain of a mouse brain impression smear showing C. psittaci. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Kingdom: | Pseudomonadati |

| Phylum: | Chlamydiota |

| Class: | Chlamydiia |

| Order: | Chlamydiales |

| Family: | Chlamydiaceae |

| Genus: | Chlamydia |

| Species: | C. psittaci |

| Binomial name | |

| Chlamydia psittaci (Lillie 1930) Page 1968 (Approved Lists 1980) | |

| Synonyms | |

Chlamydophila psittaci(Lillie 1930) Everett et al. 1999 [1] Contents | |

Chlamydia psittaci is a lethal intracellular bacterial species that may cause endemic avian chlamydiosis, epizootic outbreaks in other mammals, and respiratory psittacosis in humans. Potential hosts include feral birds and domesticated poultry, as well as cattle, pigs, sheep, and horses. C. psittaci is transmitted by inhalation, contact, or ingestion among birds and to mammals. Psittacosis in birds and in humans often starts with flu-like symptoms and becomes a life-threatening pneumonia. Many strains remain quiescent in birds until activated by stress. Birds are excellent, highly mobile vectors for the distribution of chlamydia infection, because they feed on, and have access to, the detritus of infected animals of all sorts.

Chlamydia psittaci in birds is often systemic, and infections can be inapparent, severe, acute, or chronic with intermittent shedding. [2] [3] [4] C. psittaci strains in birds infect mucosal epithelial cells and macrophages of the respiratory tract. Septicaemia eventually develops and the bacteria become localized in epithelial cells and macrophages of most organs, conjunctiva, and gastrointestinal tracts. It can also be passed in the eggs. Stress will commonly trigger onset of severe symptoms, resulting in rapid deterioration and death. C. psittaci strains are similar in virulence, grow readily in cell culture, have 16S rRNA genes that differ by <0.8%, and belong to eight known serotypes. All should be considered to be readily transmissible to humans.

Chlamydia psittaci serovar A is endemic among psittacine birds and has caused sporadic zoonotic disease in humans, other mammals, and tortoises. Serovar B is endemic among pigeons, has been isolated from turkeys, and has also been identified as the cause of abortion in herds of dairy cattle. Serovars C and D are occupational hazards for slaughterhouse workers and for people in contact with birds. Serovar E isolates (known as Cal-10, MP or MN) have been obtained from a variety of avian hosts worldwide and, although they were associated with the 1920s–1930s outbreak in humans, a specific reservoir for serovar E has not been identified. The M56 and WC serovars were isolated during outbreaks in mammals. Many C. psittaci strains are susceptible to bacteriophages.