Related Research Articles

Aramaic is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria, and quickly spread to Mesopotamia and eastern Anatolia where it has been continually written and spoken, in different varieties, for over three thousand years. Aramaic served as a language of public life and administration of ancient kingdoms and empires, and also as a language of divine worship and religious study. Several modern varieties, the Neo-Aramaic languages, are still spoken by Assyrians, and some Mandeans and Mizrahi Jews.

The Syriac language, also known as Syriac Aramaic and Classical Syriac ܠܫܢܐ ܥܬܝܩܐ, is an Aramaic dialect that emerged during the first century AD from a local Aramaic dialect that was spoken in the ancient region of Osroene, centered in the city of Edessa. During the Early Christian period, it became the main literary language of various Aramaic-speaking Christian communities in the historical region of Ancient Syria and throughout the Near East. As a liturgical language of Syriac Christianity, it gained a prominent role among Eastern Christian communities that used both Eastern Syriac and Western Syriac rites. Following the spread of Syriac Christianity, it also became a liturgical language of eastern Christian communities as far as India and China. It flourished from the 4th to the 8th century, and continued to have an important role during the next centuries, but by the end of the Middle Ages it was gradually reduced to liturgical use, since the role of vernacular language among its native speakers was overtaken by several emerging Neo-Aramaic dialects.

In phonetics, ejective consonants are usually voiceless consonants that are pronounced with a glottalic egressive airstream. In the phonology of a particular language, ejectives may contrast with aspirated, voiced and tenuis consonants. Some languages have glottalized sonorants with creaky voice that pattern with ejectives phonologically, and other languages have ejectives that pattern with implosives, which has led to phonologists positing a phonological class of glottalic consonants, which includes ejectives.

Postalveolar or post-alveolar consonants are consonants articulated with the tongue near or touching the back of the alveolar ridge. Articulation is farther back in the mouth than the alveolar consonants, which are at the ridge itself, but not as far back as the hard palate, the place of articulation for palatal consonants. Examples of postalveolar consonants are the English palato-alveolar consonants, as in the words "ship", "'chill", "vision", and "jump", respectively.

A retroflex, apico-domal, or cacuminalconsonant is a coronal consonant where the tongue has a flat, concave, or even curled shape, and is articulated between the alveolar ridge and the hard palate. They are sometimes referred to as cerebral consonants—especially in Indology.

A voiceless postalveolar fricative is a type of consonantal sound used in some spoken languages. The International Phonetic Association uses the term voiceless postalveolar fricative only for the sound, but it also describes the voiceless postalveolar non-sibilant fricative, for which there are significant perceptual differences.

The Syriac alphabet is a writing system primarily used to write the Syriac language since the 1st century AD. It is one of the Semitic abjads descending from the Aramaic alphabet through the Palmyrene alphabet, and shares similarities with the Phoenician, Hebrew, Arabic and Sogdian, the precursor and a direct ancestor of the traditional Mongolian scripts.

Turoyo, also referred to as Surayt, or modern Suryoyo, is a Central Neo-Aramaic language traditionally spoken in the Tur Abdin region in southeastern Turkey and in northern Syria. Turoyo speakers are mostly adherents of the Syriac Orthodox Church, but there are also some Turoyo-speaking adherents of the Assyrian Church of the East and the Chaldean Catholic Church, especially from the towns of Midyat and Qamishli. The language is also spoken throughout diaspora, among modern Assyrians/Syriacs. It is classified as a vulnerable language. Most speakers use the Classical Syriac language for literature and worship. Turoyo is not mutually intelligible with Western Neo-Aramaic, having been separated for over a thousand years; its closest relatives are Mlaḥsô and western varieties of Northeastern Neo-Aramaic like Suret.

Suret, also known as Assyrian or Chaldean, refers to the varieties of Northeastern Neo-Aramaic (NENA) spoken by Christians, largely ethnic Assyrians. The various NENA dialects descend from Old Aramaic, the lingua franca in the later phase of the Assyrian Empire, which slowly displaced the East Semitic Akkadian language beginning around the 10th century BC. They have been further heavily influenced by Classical Syriac, the Middle Aramaic dialect of Edessa, after its adoption as an official liturgical language of the Syriac churches, but Suret is not a direct descendant of Classical Syriac.

The Jewish Neo-Aramaic dialect of Urmia, a dialect of Northeastern Neo-Aramaic, was originally spoken by Jews in Urmia and surrounding areas of Iranian Azerbaijan from Salmas to Solduz and into what is now Yüksekova, Hakkâri and Başkale, Van Province in eastern Turkey. Most speakers now live in Israel.

Tsade is the eighteenth letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician ṣādē 𐤑, Hebrew ṣādī צ, Aramaic ṣāḏē 𐡑, Syriac ṣāḏē ܨ, Ge'ez ṣädäy ጸ, and Arabic ṣād ص. Its oldest phonetic value is debated, although there is a variety of pronunciations in different modern Semitic languages and their dialects. It represents the coalescence of three Proto-Semitic "emphatic consonants" in Canaanite. Arabic, which kept the phonemes separate, introduced variants of ṣād and ṭāʾ to express the three. In Aramaic, these emphatic consonants coalesced instead with ʿayin and ṭēt, respectively, thus Hebrew ereṣ ארץ (earth) is araʿ ארע in Aramaic.

Nenqayni Chʼih is a Northern Athabaskan language spoken in British Columbia by the Tsilhqotʼin people.

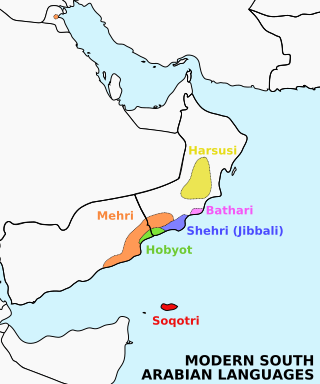

Mehri or Mahri is the most spoken of the Modern South Arabian languages (MSALs), a subgroup of the Semitic branch of the Afroasiatic family. It is spoken by the Mehri tribes, who inhabit isolated areas of the eastern part of Yemen, western Oman, particularly the Al Mahrah Governorate, with a small number in Saudi Arabia near the Yemeni and Omani borders. Up to the 19th century, speakers lived as far north as the central part of Oman.

Bohtan Neo-Aramaic is a dialect of Northeastern Neo-Aramaic originally spoken by ethnic Assyrians on the plain of Bohtan in the Ottoman Empire. Its speakers were displaced during the Assyrian genocide in 1915 and settled in Gardabani, near Rustavi in Georgia, Göygöl and Ağstafa in Azerbaijan. However it is now spoken in Moscow, Krymsk and Novopavlosk, Russia. It is considered to be a dialect of Assyrian Neo-Aramaic since it is a northeastern Aramaic language and its speakers are ethnically Assyrians.

Northeastern Neo-Aramaic (NENA) is a grouping of related dialects of Neo-Aramaic spoken before World War I as a vernacular language by Jews and Christians between the Tigris and Lake Urmia, stretching north to Lake Van and southwards to Mosul and Kirkuk. As a result of the Sayfo Christian speakers were forced out of the area that is now Turkey and in the early 1950s most Jewish speakers moved to Israel. The Kurdish-Turkish conflict resulted in further dislocations of speaker populations. As of the 1990s, the NENA group had an estimated number of fluent speakers among the Assyrians just below 500,000, spread throughout the Middle East and the Assyrian diaspora. In 2007, linguist Geoffrey Khan wrote that many dialects were nearing extinction with fluent speakers difficult to find.

The voiceless alveolar fricatives are a type of fricative consonant pronounced with the tip or blade of the tongue against the alveolar ridge just behind the teeth. This refers to a class of sounds, not a single sound. There are at least six types with significant perceptual differences:

Geoffrey Allan Khan FBA is a British linguist who has held the post of Regius Professor of Hebrew at the University of Cambridge since 2012. He has published grammars for the Aramaic dialects of Barwari, Qaraqosh, Erbil, Sulaymaniyah and Halabja in Iraq; of Urmia and Sanandaj in Iran; and leads the North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic DatabaseArchived 8 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

Palatalization is a historical-linguistic sound change that results in a palatalized articulation of a consonant or, in certain cases, a front vowel. Palatalization involves change in the place or manner of articulation of consonants, or the fronting or raising of vowels. In some cases, palatalization involves assimilation or lenition.

Kurdish phonology is the sound system of the Kurdish dialect continuum. This article includes the phonology of the three largest Kurdish dialects in their respective standard descriptions. Phonological features include the distinction between aspirated and unaspirated voiceless stops, and the large phoneme inventories.