Respiratory failure results from inadequate gas exchange by the respiratory system, meaning that the arterial oxygen, carbon dioxide, or both cannot be kept at normal levels. A drop in the oxygen carried in the blood is known as hypoxemia; a rise in arterial carbon dioxide levels is called hypercapnia. Respiratory failure is classified as either Type 1 or Type 2, based on whether there is a high carbon dioxide level, and can be acute or chronic. In clinical trials, the definition of respiratory failure usually includes increased respiratory rate, abnormal blood gases, and evidence of increased work of breathing. Respiratory failure causes an altered mental status due to ischemia in the brain.

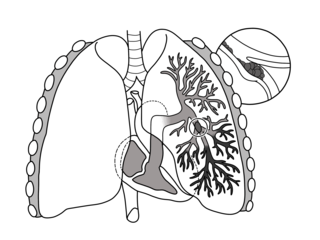

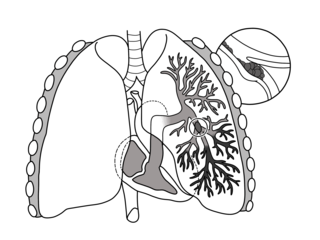

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a blockage of an artery in the lungs by a substance that has moved from elsewhere in the body through the bloodstream (embolism). Symptoms of a PE may include shortness of breath, chest pain particularly upon breathing in, and coughing up blood. Symptoms of a blood clot in the leg may also be present, such as a red, warm, swollen, and painful leg. Signs of a PE include low blood oxygen levels, rapid breathing, rapid heart rate, and sometimes a mild fever. Severe cases can lead to passing out, abnormally low blood pressure, obstructive shock, and sudden death.

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome, a group of signs and symptoms caused by an impairment of the heart's blood pumping function. Symptoms typically include shortness of breath, excessive fatigue, and leg swelling. The shortness of breath may occur with exertion or while lying down, and may wake people up during the night. Chest pain, including angina, is not usually caused by heart failure, but may occur if the heart failure was caused by a heart attack. The severity of the heart failure is measured by the severity of symptoms during exercise. Other conditions that may have symptoms similar to heart failure include obesity, kidney failure, liver disease, anemia, and thyroid disease.

Pulmonary heart disease, also known as cor pulmonale, is the enlargement and failure of the right ventricle of the heart as a response to increased vascular resistance or high blood pressure in the lungs.

Pulmonary hypertension is a condition of increased blood pressure in the arteries of the lungs. Symptoms include shortness of breath, fainting, tiredness, chest pain, swelling of the legs, and a fast heartbeat. The condition may make it difficult to exercise. Onset is typically gradual.

Endarterectomy is a surgical procedure to remove the atheromatous plaque material, or blockage, in the lining of an artery constricted by the buildup of deposits. It is carried out by separating the plaque from the arterial wall.

Pulmonary angiography is a medical fluoroscopic procedure used to visualize the pulmonary arteries and much less frequently, the pulmonary veins. It is a minimally invasive procedure performed most frequently by an interventional radiologist or interventional cardiologist to visualise the arteries of the lungs.

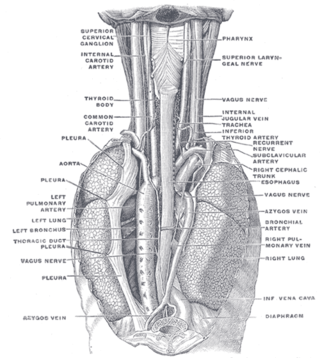

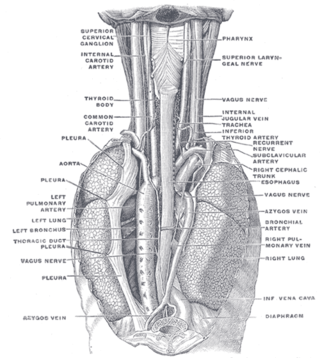

In human anatomy, the bronchial arteries supply the lungs with oxygenated blood, and nutrition. Although there is much variation, there are usually two bronchial arteries that run to the left lung, and one to the right lung, and are a vital part of the respiratory system.

Carotid artery stenosis is a narrowing or constriction of any part of the carotid arteries, usually caused by atherosclerosis.

Respiratory diseases, or lung diseases, are pathological conditions affecting the organs and tissues that make gas exchange difficult in air-breathing animals. They include conditions of the respiratory tract including the trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, alveoli, pleurae, pleural cavity, the nerves and muscles of respiration. Respiratory diseases range from mild and self-limiting, such as the common cold, influenza, and pharyngitis to life-threatening diseases such as bacterial pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, tuberculosis, acute asthma, lung cancer, and severe acute respiratory syndromes, such as COVID-19. Respiratory diseases can be classified in many different ways, including by the organ or tissue involved, by the type and pattern of associated signs and symptoms, or by the cause of the disease.

In thoracic surgery, a pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE), also referred to as pulmonary endarterectomy (PEA), is an operation that removes organized clotted blood (thrombus) from the pulmonary arteries, which supply blood to the lungs.

Portopulmonary hypertension (PPH) is defined by the coexistence of portal and pulmonary hypertension. PPH is a serious complication of liver disease, present in 0.25 to 4% of all patients with cirrhosis. Once an absolute contraindication to liver transplantation, it is no longer, thanks to rapid advances in the treatment of this condition. Today, PPH is comorbid in 4-6% of those referred for a liver transplant.

Computed tomography angiography is a computed tomography technique used for angiography—the visualization of arteries and veins—throughout the human body. Using contrast injected into the blood vessels, images are created to look for blockages, aneurysms, dissections, and stenosis. CTA can be used to visualize the vessels of the heart, the aorta and other large blood vessels, the lungs, the kidneys, the head and neck, and the arms and legs. CTA can also be used to localise arterial or venous bleed of the gastrointestinal system.

A CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) is a medical diagnostic test that employs computed tomography (CT) angiography to obtain an image of the pulmonary arteries. Its main use is to diagnose pulmonary embolism (PE). It is a preferred choice of imaging in the diagnosis of PE due to its minimally invasive nature for the patient, whose only requirement for the scan is an intravenous line.

Riociguat, sold under the brand name Adempas, is a medication by Bayer that is a stimulator of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC). It is used to treat two forms of pulmonary hypertension (PH): chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Riociguat constitutes the first drug of the class of sGC stimulators. The drug has a half-life of 12 hours and will decrease dyspnea associated with pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis is a long-term fungal infection caused by members of the genus Aspergillus—most commonly Aspergillusfumigatus. The term describes several disease presentations with considerable overlap, ranging from an aspergilloma—a clump of Aspergillus mold in the lungs—through to a subacute, invasive form known as chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis which affects people whose immune system is weakened. Many people affected by chronic pulmonary aspergillosis have an underlying lung disease, most commonly tuberculosis, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, asthma, or lung cancer.

Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD) is a rare form of pulmonary hypertension caused by progressive blockage of the small veins in the lungs. The blockage leads to high blood pressures in the arteries of the lungs, which, in turn, leads to heart failure. The disease is progressive and fatal, with median survival of about 2 years from the time of diagnosis to death. The definitive therapy is lung transplantation.

Stuart William Jamieson is a British cardiothoracic surgeon, specialising in pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE), a surgical procedure performed to remove organized clotted blood (thrombus) from pulmonary arteries in people with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH).

Balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA) is an emerging minimally invasive procedure to treat chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) in people who are not suitable for pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE) or still have residual pulmonary hypertension and areas of narrowing in the pulmonary arterial tree following previous PTE.

Arterial occlusion is a condition involving partial or complete blockage of blood flow through an artery. Arteries are blood vessels that carry oxygenated blood to body tissues. An occlusion of arteries disrupts oxygen and blood supply to tissues, leading to ischemia. Depending on the extent of ischemia, symptoms of arterial occlusion range from simple soreness and pain that can be relieved with rest, to a lack of sensation or paralysis that could require amputation.