In cryptography, a block cipher is a deterministic algorithm that operates on fixed-length groups of bits, called blocks. Block ciphers are the elementary building blocks of many cryptographic protocols. They are ubiquitous in the storage and exchange of data, where such data is secured and authenticated via encryption.

In cryptography, a cipher is an algorithm for performing encryption or decryption—a series of well-defined steps that can be followed as a procedure. An alternative, less common term is encipherment. To encipher or encode is to convert information into cipher or code. In common parlance, "cipher" is synonymous with "code", as they are both a set of steps that encrypt a message; however, the concepts are distinct in cryptography, especially classical cryptography.

A stream cipher is a symmetric key cipher where plaintext digits are combined with a pseudorandom cipher digit stream (keystream). In a stream cipher, each plaintext digit is encrypted one at a time with the corresponding digit of the keystream, to give a digit of the ciphertext stream. Since encryption of each digit is dependent on the current state of the cipher, it is also known as state cipher. In practice, a digit is typically a bit and the combining operation is an exclusive-or (XOR).

Symmetric-key algorithms are algorithms for cryptography that use the same cryptographic keys for both the encryption of plaintext and the decryption of ciphertext. The keys may be identical, or there may be a simple transformation to go between the two keys. The keys, in practice, represent a shared secret between two or more parties that can be used to maintain a private information link. The requirement that both parties have access to the secret key is one of the main drawbacks of symmetric-key encryption, in comparison to public-key encryption. However, symmetric-key encryption algorithms are usually better for bulk encryption. With exception of the one-time pad they have a smaller key size, which means less storage space and faster transmission. Due to this, asymmetric-key encryption is often used to exchange the secret key for symmetric-key encryption.

A chosen-plaintext attack (CPA) is an attack model for cryptanalysis which presumes that the attacker can obtain the ciphertexts for arbitrary plaintexts. The goal of the attack is to gain information that reduces the security of the encryption scheme.

In cryptography, an initialization vector (IV) or starting variable is an input to a cryptographic primitive being used to provide the initial state. The IV is typically required to be random or pseudorandom, but sometimes an IV only needs to be unpredictable or unique. Randomization is crucial for some encryption schemes to achieve semantic security, a property whereby repeated usage of the scheme under the same key does not allow an attacker to infer relationships between segments of the encrypted message. For block ciphers, the use of an IV is described by the modes of operation.

In cryptography, a block cipher mode of operation is an algorithm that uses a block cipher to provide information security such as confidentiality or authenticity. A block cipher by itself is only suitable for the secure cryptographic transformation of one fixed-length group of bits called a block. A mode of operation describes how to repeatedly apply a cipher's single-block operation to securely transform amounts of data larger than a block.

In cryptography, ciphertext or cyphertext is the result of encryption performed on plaintext using an algorithm, called a cipher. Ciphertext is also known as encrypted or encoded information because it contains a form of the original plaintext that is unreadable by a human or computer without the proper cipher to decrypt it. This process prevents the loss of sensitive information via hacking. Decryption, the inverse of encryption, is the process of turning ciphertext into readable plaintext. Ciphertext is not to be confused with codetext because the latter is a result of a code, not a cipher.

In cryptography, padding is any of a number of distinct practices which all include adding data to the beginning, middle, or end of a message prior to encryption. In classical cryptography, padding may include adding nonsense phrases to a message to obscure the fact that many messages end in predictable ways, e.g. sincerely yours.

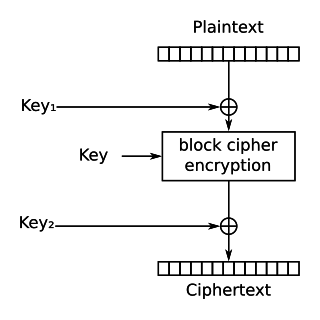

Multiple encryption is the process of encrypting an already encrypted message one or more times, either using the same or a different algorithm. It is also known as cascade encryption, cascade ciphering, multiple encryption, and superencipherment. Superencryption refers to the outer-level encryption of a multiple encryption.

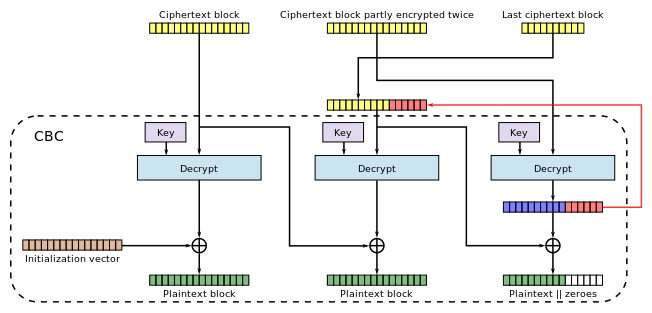

In cryptography, residual block termination is a variation of cipher block chaining mode (CBC) that does not require any padding. It does this by effectively changing to cipher feedback mode for one block. The cost is the increased complexity.

Disk encryption is a special case of data at rest protection when the storage medium is a sector-addressable device. This article presents cryptographic aspects of the problem. For an overview, see disk encryption. For discussion of different software packages and hardware devices devoted to this problem, see disk encryption software and disk encryption hardware.

In cryptography, Galois/Counter Mode (GCM) is a mode of operation for symmetric-key cryptographic block ciphers which is widely adopted for its performance. GCM throughput rates for state-of-the-art, high-speed communication channels can be achieved with inexpensive hardware resources.

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) standardization project for encryption of stored data, but more generically refers to the Security in Storage Working Group (SISWG), which includes a family of standards for protection of stored data and for the corresponding cryptographic key management.

In cryptography, a keystream is a stream of random or pseudorandom characters that are combined with a plaintext message to produce an encrypted message.

In cryptography, format-preserving encryption (FPE), refers to encrypting in such a way that the output is in the same format as the input. The meaning of "format" varies. Typically only finite sets of characters are used; numeric, alphabetic or alphanumeric. For example:

There are various implementations of the Advanced Encryption Standard, also known as Rijndael.

In cryptography, a padding oracle attack is an attack which uses the padding validation of a cryptographic message to decrypt the ciphertext. In cryptography, variable-length plaintext messages often have to be padded (expanded) to be compatible with the underlying cryptographic primitive. The attack relies on having a "padding oracle" who freely responds to queries about whether a message is correctly padded or not. Padding oracle attacks are mostly associated with CBC mode decryption used within block ciphers. Padding modes for asymmetric algorithms such as OAEP may also be vulnerable to padding oracle attacks.

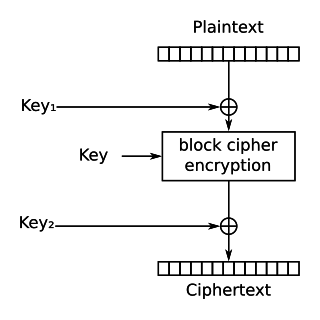

The xor–encrypt–xor (XEX) is a (tweakable) mode of operation of a block cipher. In tweaked-codebook mode with ciphertext stealing, it is one of the more popular modes of operation for whole-disk encryption. XEX is also a common form of key whitening, and part of some smart card proposals.

Crypto-PAn is a cryptographic algorithm for anonymizing IP addresses while preserving their subnet structure. That is, the algorithm encrypts any string of bits to a new string , while ensuring that for any pair of bit-strings which share a common prefix of length , their images also share a common prefix of length . A mapping with this property is called prefix-preserving. In this way, Crypto-PAn is a kind of format-preserving encryption.