The United Kingdom's Climate Change Programme was launched in November 2000 by the British government in response to its commitment agreed at the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED). The 2000 programme was updated in March 2006 following a review launched in September 2004.

The Climate Change Levy (CCL) is a tax on energy delivered to non-domestic users in the United Kingdom.

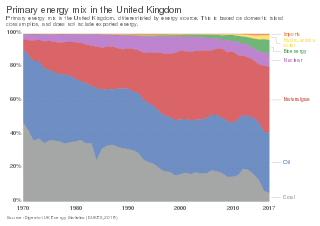

Energy in the United Kingdom came mostly from fossil fuels in 2021. Total energy consumption in the United Kingdom was 142.0 million tonnes of oil equivalent in 2019. In 2014, the UK had an energy consumption per capita of 2.78 tonnes of oil equivalent compared to a world average of 1.92 tonnes of oil equivalent. Demand for electricity in 2014 was 34.42 GW on average coming from a total electricity generation of 335.0 TWh.

Various energy conservation measures are taken in the United Kingdom.

The energy policy of the United Kingdom refers to the United Kingdom's efforts towards reducing energy intensity, reducing energy poverty, and maintaining energy supply reliability. The United Kingdom has had success in this, though energy intensity remains high. There is an ambitious goal to reduce carbon dioxide emissions in future years, but it is unclear whether the programmes in place are sufficient to achieve this objective. Regarding energy self-sufficiency, UK policy does not address this issue, other than to concede historic energy security is currently ceasing to exist.

Energy Saving Trust is a British organization devoted to promoting energy efficiency, energy conservation, and the sustainable use of energy, thereby reducing carbon dioxide emissions and helping to prevent man-made climate change. It was founded in the United Kingdom as a government-sponsored initiative in 1992, following the global Earth Summit.

The United States produced 5.2 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2020, the second largest in the world after greenhouse gas emissions by China and among the countries with the highest greenhouse gas emissions per person. In 2019 China is estimated to have emitted 27% of world GHG, followed by the United States with 11%, then India with 6.6%. In total the United States has emitted a quarter of world GHG, more than any other country. Annual emissions are over 15 tons per person and, amongst the top eight emitters, is the highest country by greenhouse gas emissions per person. However, the IEA estimates that the richest decile in the US emits over 55 tonnes of CO2 per capita each year. Because coal-fired power stations are gradually shutting down, in the 2010s emissions from electricity generation fell to second place behind transportation which is now the largest single source. In 2020, 27% of the GHG emissions of the United States were from transportation, 25% from electricity, 24% from industry, 13% from commercial and residential buildings and 11% from agriculture. In 2021, the electric power sector was the second largest source of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for 25% of the U.S. total. These greenhouse gas emissions are contributing to climate change in the United States, as well as worldwide.

The CRC Energy Efficiency Scheme was a mandatory carbon emissions reduction scheme in the United Kingdom which applied to large energy-intensive organisations in the public and private sectors. It was estimated that the scheme would reduce carbon emissions by 1.2 million tonnes of carbon per year by 2020. In an effort to avoid dangerous climate change, the British Government first committed to cutting UK carbon emissions by 60% by 2050, and in October 2008 increased this commitment to 80%. The scheme has also been credited with driving up demand for energy-efficient goods and services.

Renewable energy in the United Kingdom contributes to production for electricity, heat, and transport.

The Global Warming Pollution Reduction Act of 2007 (S. 309) was a bill proposed to amend the 1963 Clean Air Act, a bill that aimed to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2). U.S. Senator, Bernie Sanders (I-VT), introduced the resolution in the 110th United States Congress on January 16, 2007. The bill was referred to the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works but was not enacted into law.

Sustainable development in Scotland has a number of distinct strands. The idea of sustainable development was used by the Brundtland Commission which defined it as development that "meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs." At the 2005 World Summit it was noted that this requires the reconciliation of environmental, social and economic demands - the "three pillars" of sustainability. These general aims are being addressed in a diversity of ways by the public, private, voluntary and community sectors in Scotland.

Greenhouse gas emissions by Australia totalled 533 million tonnes CO2-equivalent based on greenhouse gas national inventory report data for 2019; representing per capita CO2e emissions of 21 tons, three times the global average. Coal was responsible for 30% of emissions. The national Greenhouse Gas Inventory estimates for the year to March 2021 were 494.2 million tonnes, which is 27.8 million tonnes, or 5.3%, lower than the previous year. It is 20.8% lower than in 2005. According to the government, the result reflects the decrease in transport emissions due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, reduced fugitive emissions, and reductions in emissions from electricity; however, there were increased greenhouse gas emissions from the land and agriculture sectors.

Climate change is impacting the environment and human population of the United Kingdom (UK). The country's climate is becoming warmer, with drier summers and wetter winters. The frequency and intensity of storms, floods, droughts and heatwaves is increasing, and sea level rise is impacting coastal areas. The UK is also a contributor to climate change, having emitted more greenhouse gas per person than the world average. Climate change is having economic impacts on the UK and presents risks to human health and ecosystems.

The Kyoto Protocol was an international treaty which extended the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. A number of governments across the world took a variety of actions.

In 2021, net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the United Kingdom (UK) were 427 million tonnes (Mt) carbon dioxide equivalent, 80% of which was carbon dioxide itself. Emissions increased by 5% in 2021 with the easing of COVID-19 restrictions, primarily due to the extra road transport. The UK has over time emitted about 3% of the world total human caused CO2, with a current rate under 1%, although the population is less than 1%.

The United Kingdom is committed to legally binding greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets of 34% by 2020 and 80% by 2050, compared to 1990 levels, as set out in the Climate Change Act 2008. Decarbonisation of electricity generation will form a major part of this reduction and is essential before other sectors of the economy can be successfully decarbonised.

A carbon pricing scheme in Australia was introduced by the Gillard Labor minority government in 2011 as the Clean Energy Act 2011 which came into effect on 1 July 2012. Emissions from companies subject to the scheme dropped 7% upon its introduction. As a result of being in place for such a short time, and because the then Opposition leader Tony Abbott indicated he intended to repeal "the carbon tax", regulated organizations responded rather weakly, with very few investments in emissions reductions being made. The scheme was repealed on 17 July 2014, backdated to 1 July 2014. In its place the Abbott government set up the Emission Reduction Fund in December 2014. Emissions thereafter resumed their growth evident before the tax.

The Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 is an Act of the Scottish Parliament. The Act includes an emissions target, set for the year 2050, for a reduction of at least 80% from the baseline year, 1990. Annual targets for greenhouse gas emissions must also be set, after consultation the relevant advisory bodies.

Climate change is leading to long-term impacts on agriculture in Germany, more intense heatwaves and coldwaves, flash and coastal flooding, and reduced water availability. Debates over how to address these long-term challenges caused by climate change have also sparked changes in the energy sector and in mitigation strategies. Germany's energiewende has been a significant political issue in German politics that has made coalition talks difficult for Angela Merkel's CDU.

Climate change in South Africa is leading to increased temperatures and rainfall variability. Evidence shows that extreme weather events are becoming more prominent due to climate change. This is a critical concern for South Africans as climate change will affect the overall status and wellbeing of the country, for example with regards to water resources. Just like many other parts of the world, climate research showed that the real challenge in South Africa was more related to environmental issues rather than developmental ones. The most severe effect will be targeting the water supply, which has huge effects on the agriculture sector. Speedy environmental changes are resulting in clear effects on the community and environmental level in different ways and aspects, starting with air quality, to temperature and weather patterns, reaching out to food security and disease burden.