Related Research Articles

The Waldorf Astoria New York is a luxury hotel and condominium residence in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. The structure, at 301 Park Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets, is a 47-story 625 ft (191 m) Art Deco landmark designed by architects Schultze and Weaver, which was completed in 1931. The building was the world's tallest hotel until 1963 when it was surpassed by Moscow's Hotel Ukraina. An icon of glamour and luxury, the Waldorf Astoria is one of the world's most prestigious and best-known hotels. Waldorf Astoria Hotels & Resorts was a division of Hilton Hotels, and a portfolio of high-end properties around the world operates under the name, including in New York City. Both the exterior and the interior of the Waldorf Astoria are designated by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission as official landmarks.

Countee Cullen was an American poet, novelist, children's writer, and playwright, particularly well known during the Harlem Renaissance.

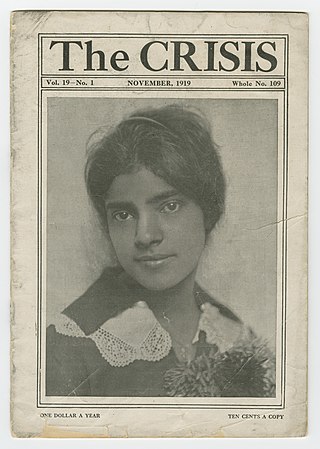

The Crisis is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Miller, William Stanley Braithwaite, and Mary Dunlop Maclean. The Crisis has been in continuous print since 1910, and it is the oldest Black-oriented magazine in the world. Today, The Crisis is "a quarterly journal of civil rights, history, politics and culture and seeks to educate and challenge its readers about issues that continue to plague African Americans and other communities of color."

Arna Wendell Bontemps was an American poet, novelist and librarian, and a noted member of the Harlem Renaissance.

Niggerati was the name used, with deliberate irony, by Wallace Thurman for the group of young African-American artists and intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance. "Niggerati" is a portmanteau of "nigger" and "literati". The rooming house where he lived, and where that group often met, was similarly christened Niggerati Manor. The group included Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, and several of the people behind Thurman's journal FIRE!!, such as Richard Bruce Nugent, Jonathan Davis, Gwendolyn Bennett, and Aaron Douglas.

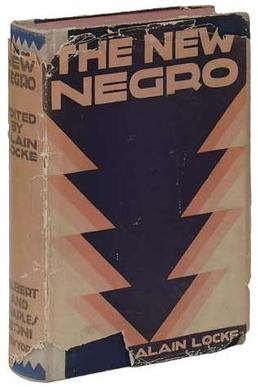

The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925) is an anthology of fiction, poetry, and essays on African and African-American art and literature edited by Alain Locke, who lived in Washington, DC, and taught at Howard University during the Harlem Renaissance. As a collection of the creative efforts coming out of the burgeoning New Negro Movement or Harlem Renaissance, the book is considered by literary scholars and critics to be the definitive text of the movement. "The Negro Renaissance" included Locke's title essay "The New Negro", as well as nonfiction essays, poetry, and fiction by writers including Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, and Eric Walrond.

Not Without Laughter is the debut novel by Langston Hughes published in 1930.

Fire!! was an African-American literary magazine published in New York City in 1926 during the Harlem Renaissance. The publication was started by Wallace Thurman, Zora Neale Hurston, Aaron Douglas, John P. Davis, Richard Bruce Nugent, Gwendolyn Bennett, Lewis Grandison Alexander, Countee Cullen, and Langston Hughes. The magazine's title referred to burning up old ideas, and Fire!! challenged the norms of the older Black generation while featuring younger authors. The publishers promoted a realistic style, with vernacular language and controversial topics such as homosexuality and prostitution. Many readers were offended, and some Black leaders denounced the magazine. The endeavor was plagued by debt, and its quarters burned down, ending the magazine after just one issue.

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the time, it was known as the "New Negro Movement", named after The New Negro, a 1925 anthology edited by Alain Locke. The movement also included the new African American cultural expressions across the urban areas in the Northeast and Midwest United States affected by a renewed militancy in the general struggle for civil rights, combined with the Great Migration of African American workers fleeing the racist conditions of the Jim Crow Deep South, as Harlem was the final destination of the largest number of those who migrated north.

The Waldorf-Astoria Orchestra was an orchestra that played primarily at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, both the old and new locations. In addition to providing dinner music at the famous hotel, the orchestra made over 300 recordings and many radio broadcasts. It was established in the 1890s, and was directed by Carlo Curti in early 1900s, Joseph Knecht at least from 1908 to 1925, later by Jack Denny and others, and then Xavier Cugat from approximately 1933 to 1949.

James Mercer Langston Hughes was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri. One of the earliest innovators of the literary art form called jazz poetry, Hughes is best known as a leader of the Harlem Renaissance. He famously wrote about the period that "the Negro was in vogue", which was later paraphrased as "when Harlem was in vogue."

"On the Pulse of Morning" is a poem by writer and poet Maya Angelou that she read at the first inauguration of President Bill Clinton on January 20, 1993. With her public recitation, Angelou became the second poet in history to read a poem at a presidential inauguration, and the first African American and woman. Angelou's audio recording of the poem won the 1994 Grammy Award in the "Best Spoken Word" category, resulting in more fame and recognition for her previous works, and broadening her appeal.

Prentiss Taylor was an American illustrator, lithographer, and painter. Born in Washington D.C., Taylor began his art studies at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, followed by painting classes under Charles Hawthorne in Provincetown, Massachusetts, and training at the Art Students League in New York City. In 1931, Taylor began studying lithography at the League. He became a member of one of the most important printmaking societies in America at that time, the Society of American Graphic Artists. Taylor interacted and collaborated with many writers and musicians in his time in New York in the late 1920s and early 30s. This was in the emergence of the Harlem Renaissance. Among his close friends and colleagues were Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten.

"The Weary Blues" is a poem by American poet Langston Hughes. Written in 1925, "The Weary Blues" was first published in the Urban League magazine Opportunity. It was awarded the magazine's prize for best poem of the year. The poem was included in Hughes's first book, a collection of poems, also entitled The Weary Blues.

"The Negro Speaks of Rivers" is a poem by American writer Langston Hughes. Hughes wrote the poem when he was 17 and crossing the Mississippi River on the way to visit his father in Mexico. It was first published the following year in The Crisis, starting Hughes's literary career. "The Negro Speaks of Rivers" uses rivers as a metaphor for Hughes's life and the broader African-American experience. It has been reprinted often and is considered one of Hughes's most famous and signature works.

Margaret Danner (1915–1984) was an American poet, editor and cultural activist known for her poetic imagery and her celebration of African heritage and cultural forms.

The official residence of the United States Ambassador to the United Nations, established in 1947, was originally located in a suite of rooms on the 42nd floor of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City leased by the U.S. Department of State. Described in press reports as "palatial", the ambassadorial residence was the first one to be located in a hotel. The Department of State vacated the Waldorf Astoria shortly after the Chinese Anbang Insurance Company purchased the Waldorf-Astoria in 2015, raising security concerns. The United States purchased a penthouse apartment at 50 United Nations Plaza in May 2019 after initially renting a different penthouse apartment in the same building.

Louise E. Jefferson (1908–2002) was an American artist.

"Mother to Son" is a 1922 poem written by Langston Hughes. The poem follows a mother speaking to her son about her life, which she says "ain't been no crystal stair". She first describes the struggles she has faced and then urges him to continue moving forward. It was referenced by Martin Luther King Jr. several times in his speeches during the civil rights movement, and has been analyzed by several critics, notably for its style and representation of the mother.

The Big Sea (1940) is an autobiographical work by Langston Hughes. In it, he tells his experience of being a writer of color in Paris, France, and his experiences living in New York, where he faced injustices surrounding systematic racism. In his time in Paris, Hughes struggled to find a stable income and had to learn to be efficient by taking many odd jobs like working in nightclubs and small writing jobs. Eventually, he began to rise to fame as a writer, Hughes began referencing his past struggles regarding abuse from his father where he was divided between the trauma his father endured versus the damage it did to Hughes. Hughes's autobiography exemplifies the obstacles that many African-American artists faced during the early twentieth century in the United States.

References

- ↑ Hughes, Langston. "Come to the Waldorf-Astoria!" in Pau Lautner (ed.), The Heath Anthology of American Literature. vol. D. Boston, MA: Wadsworth, Cengage, 2010. 1553. Print.

- 1 2 Rampersad, Arnold, The Life of Langston Hughes Volume 1: 1902-1941. I, Too, Sing America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986. Print.

- ↑ Hughes, Langston, The Big Sea: An Autobiography. Quoted in Modern American Poetry. 2001. University of Illinois. 2001. Web. October 23, 2011.

- ↑ Wright, Richard. A Journal of Opinion. October 28, 1941. Reprinted in Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and K. A. Appiah (eds), Langston Hughes: Critical Perspectives Past and Present, New York: Harper, 2000. Print.

- ↑ Smethurst, James. "The Adventures of a Social Poet", in Steven C. Tracy (ed.), A Historical Guide to Langston Hughes, New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. Print.