Nicholas Vachel Lindsay was an American poet. He is considered a founder of modern singing poetry, as he referred to it, in which verses are meant to be sung or chanted.

Countee Cullen was an American poet, novelist, children's writer, and playwright, particularly well known during the Harlem Renaissance.

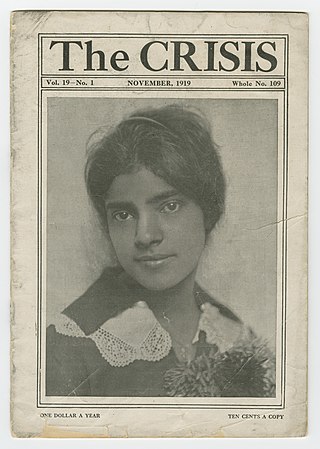

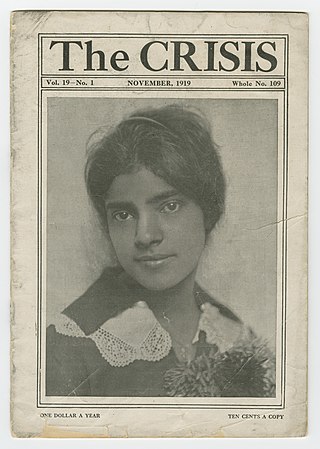

The Crisis is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Miller, William Stanley Braithwaite, and Mary Dunlop Maclean. The Crisis has been in continuous print since 1910, and it is the oldest Black-oriented magazine in the world. Today, The Crisis is "a quarterly journal of civil rights, history, politics and culture and seeks to educate and challenge its readers about issues that continue to plague African Americans and other communities of color."

Jessie Redmon Fauset was an editor, poet, essayist, novelist, and educator. Her literary work helped sculpt African-American literature in the 1920s as she focused on portraying a true image of African-American life and history. Her black fictional characters were working professionals which was an inconceivable concept to American society during this time Her story lines related to themes of racial discrimination, "passing", and feminism.

Arna Wendell Bontemps was an American poet, novelist and librarian, and a noted member of the Harlem Renaissance.

Nigger Heaven is a novel written by Carl Van Vechten, and published in October 1926. The book is set during the Harlem Renaissance in the United States in the 1920s. The book and its title have been controversial since its publication.

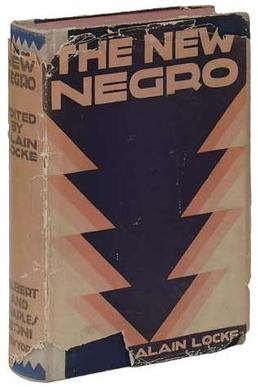

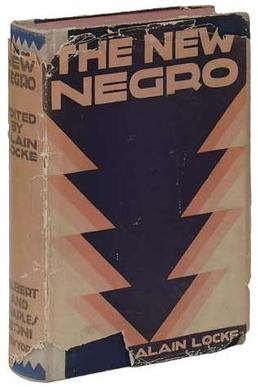

The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925) is an anthology of fiction, poetry, and essays on African and African-American art and literature edited by Alain Locke, who lived in Washington, DC, and taught at Howard University during the Harlem Renaissance. As a collection of the creative efforts coming out of the burgeoning New Negro Movement or Harlem Renaissance, the book is considered by literary scholars and critics to be the definitive text of the movement. "The Negro Renaissance" included Locke's title essay "The New Negro", as well as nonfiction essays, poetry, and fiction by writers including Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, and Eric Walrond.

Jazz poetry has been defined as poetry that "demonstrates jazz-like rhythm or the feel of improvisation" and also as poetry that takes jazz music, musicians, or the jazz milieu as its subject. Some critics consider it a distinct genre though others consider the term to be merely descriptive. Jazz poetry has long been something of an "outsider" art form that exists somewhere outside the mainstream, having been conceived in the 1920s by African Americans, maintained in the 1950s by counterculture poets like those of the Beat generation, and adapted in modern times into hip-hop music and live poetry events known as poetry slams.

Margaret Allison Bonds was an American composer, pianist, arranger, and teacher. One of the first Black composers and performers to gain recognition in the United States, she is best remembered today for her popular arrangements of African-American spirituals and frequent collaborations with Langston Hughes.

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the time, it was known as the "New Negro Movement", named after The New Negro, a 1925 anthology edited by Alain Locke. The movement also included the new African American cultural expressions across the urban areas in the Northeast and Midwest United States affected by a renewed militancy in the general struggle for civil rights, combined with the Great Migration of African American workers fleeing the racist conditions of the Jim Crow Deep South, as Harlem was the final destination of the largest number of those who migrated north.

Cane is a 1923 novel by noted Harlem Renaissance author Jean Toomer. The novel is structured as a series of vignettes revolving around the origins and experiences of African Americans in the United States. The vignettes alternate in structure between narrative prose, poetry, and play-like passages of dialogue. As a result, the novel has been classified as a composite novel or as a short story cycle. Though some characters and situations recur between vignettes, the vignettes are mostly freestanding, tied to the other vignettes thematically and contextually more than through specific plot details.

James Mercer Langston Hughes was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri. One of the earliest innovators of the literary art form called jazz poetry, Hughes is best known as a leader of the Harlem Renaissance. He famously wrote about the period that "the Negro was in vogue", which was later paraphrased as "when Harlem was in vogue."

"The Weary Blues" is a poem by American poet Langston Hughes. Written in 1925, "The Weary Blues" was first published in the Urban League magazine Opportunity. It was awarded the magazine's prize for best poem of the year. The poem was included in Hughes's first book, a collection of poems, also entitled The Weary Blues.

Lewis Grandison Alexander was an American poet, actor, playwright, and costume designer who lived in Washington, D.C., and had strong ties to the Harlem Renaissance period in New York. Alexander focused most of his time and creativity on poetry, and it is for this that he is best known.

The Brownies' Book was the first magazine published for African-American children and youth. Its creation was mentioned in the yearly children's issue of The Crisis in October 1919. The first issue was published during the Harlem Renaissance in January 1920, with issues published monthly until December 1921. It is cited as an "important moment in literary history" for establishing black children's literature in the United States.

The Negro in Art: How Shall He Be Portrayed? was the title of a 1926 symposium hosted on the pages of The Crisis, the magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Over seven issues, various figures in American literary culture answered seven questions posed by the editors. According to scholar A.B. Christa Schwarz, the symposium's articles are an enduring resource, with relevance to "attitudes toward the black−white literary marketplace on the crucial issue of representation."

"Mother to Son" is a 1922 poem written by Langston Hughes. The poem follows a mother speaking to her son about her life, which she says "ain't been no crystal stair". She first describes the struggles she has faced and then urges him to continue moving forward. It was referenced by Martin Luther King Jr. several times in his speeches during the civil rights movement, and has been analyzed by several critics, notably for its style and representation of the mother.

"Harlem" is a poem by Langston Hughes. These eleven lines ask, "What happens to a dream deferred?", providing reference to the African-American experience. It was published as part of a longer volume-length poem suite in 1951 called Montage of a Dream Deferred, but is often excerpted from the larger work. The play A Raisin in the Sun was titled after a line in the poem.

The Book of American Negro Poetry is a 1922 poetry anthology that was compiled by James Weldon Johnson. The first edition, published in 1922, was "the first of its kind ever published" and included the works of thirty-one poets. A second edition was released in 1931 with works by nine additional poets.

An Anthology of Verse by American Negroes is a 1924 poetry anthology compiled by Newman Ivey White and Walter Clinton Jackson. The anthology is considered one of the major anthologies of black poetry to be published during the Harlem Renaissance, and was republished in 1969. In reviews, the anthology has been positively received for the effort it made to compile poetry, but criticized for ambiguous criticism and poor selection of poems.