Altaic is a controversial proposed language family that would include the Turkic, Mongolic and Tungusic language families and possibly also the Japonic and Koreanic languages. The hypothetical language family has long been rejected by most comparative linguists, although it continues to be supported by a small but stable scholarly minority. Speakers of the constituent languages are currently scattered over most of Asia north of 35° N and in some eastern parts of Europe, extending in longitude from the Balkan Peninsula to Japan. The group is named after the Altai mountain range in the center of Asia.

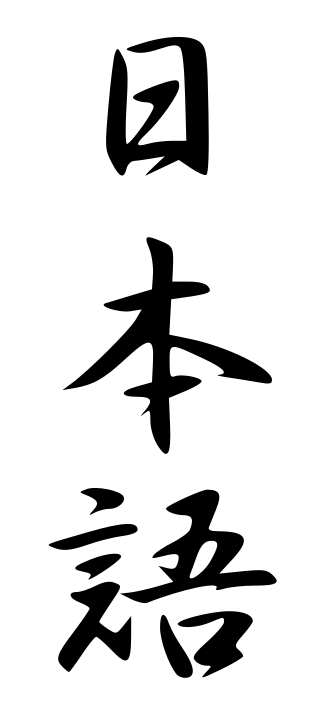

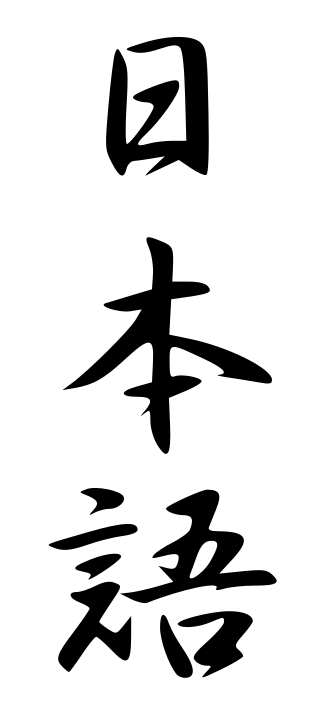

Japanese is the principal language of the Japonic language family spoken by the Japanese people. It has around 128 million speakers, primarily in Japan, the only country where it is the national language, and within the Japanese diaspora worldwide.

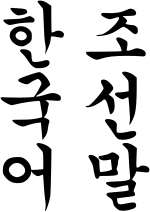

Korean is the native language for about 81.7 million people, mostly of Korean descent. It is the official and national language of both South Korea and North Korea. The two countries have established standardized norms for Korean, and the differences between them are similar to those between Standard Chinese in mainland China and Taiwan, but political conflicts between the two countries have highlighted the differences between them. South Korean newspaper Daily NK has claimed North Korea criminalizes the use of the South's standard language with the death penalty, and South Korean education and media often portray the North's language as alien and uncomfortable.

The Turkic languages are a language family of more than 35 documented languages, spoken by the Turkic peoples of Eurasia from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe to Central Asia, East Asia, North Asia (Siberia), and West Asia. The Turkic languages originated in a region of East Asia spanning from Mongolia to Northwest China, where Proto-Turkic is thought to have been spoken, from where they expanded to Central Asia and farther west during the first millennium. They are characterized as a dialect continuum.

Ural-Altaic, Uralo-Altaic or Uraltaic is a linguistic convergence zone and abandoned language-family proposal uniting the Uralic and the Altaic languages. It is generally now agreed that even the Altaic languages do not share a common descent: the similarities among Turkic, Mongolic and Tungusic are better explained by diffusion and borrowing. Just as Altaic, internal structure of the Uralic family also has been debated since the family was first proposed. Doubts about the validity of most or all of the proposed higher-order Uralic branchings are becoming more common. The term continues to be used for the central Eurasian typological, grammatical and lexical convergence zone.

Asia is home to hundreds of languages comprising several families and some unrelated isolates. The most spoken language families on the continent include Austroasiatic, Austronesian, Japonic, Dravidian, Indo-European, Afroasiatic, Turkic, Sino-Tibetan and Kra–Dai. Many languages of Asia, such as Kurdish, Sanskrit, Arabic or Tamil, have a long history as a written language.

The Mongolic languages are a language family spoken by the Mongolic peoples in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, North Asia and East Asia, mostly in Mongolia and surrounding areas and in Kalmykia and Buryatia. The best-known member of this language family, Mongolian, is the primary language of most of the residents of Mongolia and the Mongol residents of Inner Mongolia, with an estimated 5.7+ million speakers.

The languages of East Asia belong to several distinct language families, with many common features attributed to interaction. In the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, Chinese varieties and languages of southeast Asia share many areal features, tending to be analytic languages with similar syllable and tone structure. In the 1st millennium AD, Chinese culture came to dominate East Asia, and Classical Chinese was adopted by scholars and ruling classes in Vietnam, Korea, and Japan. As a consequence, there was a massive influx of loanwords from Chinese vocabulary into these and other neighboring Asian languages. The Chinese script was also adapted to write Vietnamese, Korean and Japanese, though in the first two the use of Chinese characters is now restricted to university learning, linguistic or historical study, artistic or decorative works and newspapers, rather than daily usage.

The Tungusic languages form a language family spoken in Eastern Siberia and Manchuria by Tungusic peoples. Many Tungusic languages are endangered. There are approximately 75,000 native speakers of the dozen living languages of the Tungusic language family. The term "Tungusic" is from an exonym for the Evenk people (Ewenki) used by the Yakuts ("tongus").

Japonic or Japanese–Ryukyuan, sometimes also Japanic, is a language family comprising Japanese, spoken in the main islands of Japan, and the Ryukyuan languages, spoken in the Ryukyu Islands. The family is universally accepted by linguists, and significant progress has been made in reconstructing the proto-language, Proto-Japonic. The reconstruction implies a split between all dialects of Japanese and all Ryukyuan varieties, probably before the 7th century. The Hachijō language, spoken on the Izu Islands, is also included, but its position within the family is unclear.

Uralo-Siberian is a hypothetical language family consisting of Uralic, Yukaghir, and Eskaleut. It was proposed in 1998 by Michael Fortescue, an expert in Eskaleut and Chukotko-Kamchatkan, in his book Language Relations across Bering Strait. Some have attempted to include Nivkh in Uralo-Siberian. Until 2011, it also included Chukotko-Kamchatkan. However, after 2011 Fortescue only included Uralic, Yukaghir and Eskaleut in the theory, although he argued that Uralo-Siberian languages have influenced Chukotko-Kamchatkan.

The Turco-Mongol or Turko-Mongol tradition was an ethnocultural synthesis that arose in Asia during the 14th century, among the ruling elites of the Golden Horde and the Chagatai Khanate. The ruling Mongol elites of these Khanates eventually assimilated into the Turkic populations that they conquered and ruled over, thus becoming known as Turco-Mongols. These elites gradually adopted Islam as well as Turkic languages, while retaining Mongol political and legal institutions.

The classification of the Japonic languages and their external relations is unclear. Linguists traditionally consider the Japonic languages to belong to an independent family; indeed, until the classification of Ryukyuan as separate languages within a Japonic family rather than as dialects of Japanese, Japanese was considered a language isolate.

The traditional periodization of Korean distinguishes:

Ralf-Stefan Georg is a German linguist. He is currently Professor at the University of Bonn in Bonn, Germany, for Altaic Linguistics and Culture Studies.

Koreanic is a small language family consisting of the Korean and Jeju languages. The latter is often described as a dialect of Korean, but is distinct enough to be considered a separate language. Alexander Vovin suggested that the Yukjin dialect of the far northeast should be similarly distinguished. Korean has been richly documented since the introduction of the Hangul alphabet in the 15th century. Earlier renditions of Korean using Chinese characters are much more difficult to interpret.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the Korean language:

Martine Irma Robbeets is a Belgian comparative linguist and japanologist. She is known for the Transeurasian languages hypothesis, which groups the Japonic, Koreanic, Tungusic, Mongolic, and Turkic languages together into a single language family.

The Ainu languages, sometimes known as Ainuic, are a small language family, often regarded as a language isolate, historically spoken by the Ainu people of northern Japan and neighboring islands.

The farming/language dispersal hypothesis proposes that many of the largest language families in the world dispersed along with the expansion of agriculture. This hypothesis was proposed by archaeologists Peter Bellwood and Colin Renfrew. It has been widely debated and archaeologists, linguists, and geneticists often disagree with all or only parts of the hypothesis.