A ghost ship, also known as a phantom ship, is a vessel with no living crew aboard; it may be a fictional ghostly vessel, such as the Flying Dutchman, or a physical derelict found adrift with its crew missing or dead, like the Mary Celeste. The term is sometimes used for ships that have been decommissioned but not yet scrapped, as well as drifting boats that have been found after breaking loose of their ropes and being carried away by the wind or the waves.

Capsizing or keeling over occurs when a boat or ship is rolled on its side or further by wave action, instability or wind force beyond the angle of positive static stability or it is upside down in the water. The act of recovering a vessel from a capsize is called righting. Capsize may result from broaching, knockdown, loss of stability due to cargo shifting or flooding, or in high speed boats, from turning too fast.

SS Marine Electric was a 605-foot bulk carrier that sank on 12 February 1983, about 30 miles off the coast of Virginia, in 130 feet of water. Thirty-one of the 34 crewmembers were killed; the three survivors endured 90 minutes drifting in the frigid waters of the Atlantic. The wreck resulted in some of the most important maritime reforms in the second half of the 20th century. The tragedy tightened inspection standards, resulted in mandatory survival suits for winter North Atlantic runs, and helped create the now famous Coast Guard rescue swimmer program.

The 1979 Fastnet Race was the 28th Royal Ocean Racing Club's Fastnet Race, a yachting race held generally every two years since 1925 on a 605-mile course from Cowes direct to the Fastnet Rock and then to Plymouth via south of the Isles of Scilly. In 1979, it was the climax of the five-race Admiral's Cup competition, as it had been since 1957.

West Island College (WIC) is a system of three Canadian private schools: West Island College Montreal, founded in 1974, West Island College Calgary, founded in 1982, and Class Afloat–West Island College International, founded in 1984.

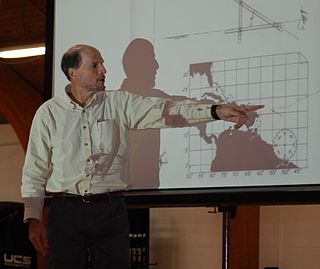

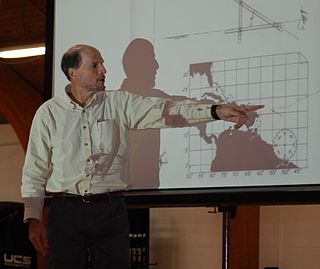

Steven Callahan is an American author, naval architect, inventor, and sailor. In 1981, he survived for 76 days adrift on the Atlantic Ocean in a liferaft. Callahan recounted his ordeal in the best-selling book Adrift: Seventy-six Days Lost at Sea (1986), which was on The New York Times best-seller list for more than 36 weeks.

A lifeboat or liferaft is a small, rigid or inflatable boat carried for emergency evacuation in the event of a disaster aboard a ship. Lifeboat drills are required by law on larger commercial ships. Rafts (liferafts) are also used. In the military, a lifeboat may double as a whaleboat, dinghy, or gig. The ship's tenders of cruise ships often double as lifeboats. Recreational sailors usually carry inflatable liferafts, though a few prefer small proactive lifeboats that are harder to sink and can be sailed to safety.

L'Acadien II was a Canadian-registered fishing vessel that capsized and sank on March 29, 2008. The vessel was being towed by Canadian Coast Guard Ship (CCGS) Sir William Alexander off Cape Breton, Nova Scotia at the time of the incident. Two of the crew of six were rescued and four men died in the incident. Recovery efforts have not located the sunken trawler nor the missing crew member who is now presumed dead. Canadian authorities have launched independent investigations into the incident.

MV Princess of the Stars was a passenger ferry owned by Filipino shipping company Sulpicio Lines, that capsized and sank on June 21, 2008, off the coast of San Fernando, Romblon, at the height of Typhoon Fengshen, which passed directly over Romblon as a Category 2 storm. 814 people died.

The Hull triple trawler tragedy was the sinking of three trawlers from the British fishing port of Kingston upon Hull during January and February 1968. A total of 58 crew members died, with just one survivor. The three sinkings brought widespread national publicity to the conditions in which fishermen worked, and triggered an official inquiry which led to major changes to employment and working practices within the British fishing industry.

SS Primrose Hill was a British CAM ship that saw action in World War II, armed with a catapult on her bow to launch a Hawker Sea Hurricane. She was completed by William Hamilton & Co in Port Glasgow on the Firth of Clyde in September 1941.

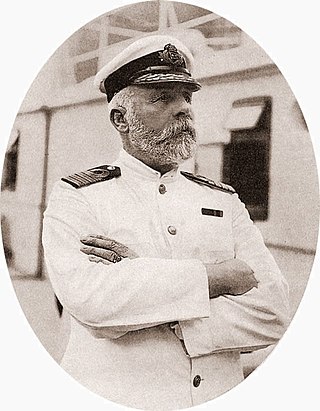

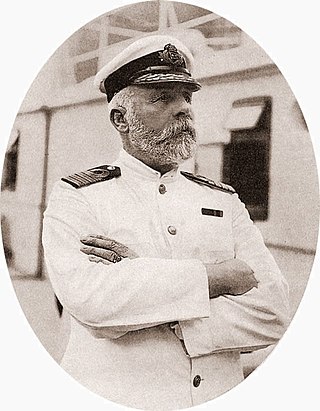

"The captain goes down with the ship" is a maritime tradition that a sea captain holds the ultimate responsibility for both the ship and everyone embarked on it, and in an emergency they will devote their time to save those on board or die trying. Although often connected to the sinking of RMS Titanic in 1912 and its captain, Edward Smith, the tradition precedes Titanic by several years. In most instances, captains forgo their own rapid departure of a ship in distress, and concentrate instead on saving other people. It often results in either the death or belated rescue of the captain as the last person on board.

SSPrincipessa Mafalda was an Italian transatlantic ocean liner built for the Navigazione Generale Italiana (NGI) company. Named after Princess Mafalda of Savoy, second daughter of King Victor Emmanuel III, the ship was completed and entered NGI's South American service between Genoa and Buenos Aires in 1909. Her sister ship SS Principessa Jolanda sank immediately upon launching on 22 September 1907.

Michael Thomas Doleman is an Australian maritime worker and trade union official.

MS Estonia sank on Wednesday, 28 September 1994, between about 00:50 and 01:50 (UTC+2) as the ship was crossing the Baltic Sea, en route from Tallinn, Estonia, to Stockholm, Sweden. The sinking was one of the worst maritime disasters of the 20th century. It is one of the deadliest peacetime sinkings of a European ship, after the Titanic in 1912 and the Empress of Ireland in 1914, and the deadliest peacetime shipwreck to have occurred in European waters, with 852 lives stated at the time as officially lost.