Mumps is a viral disease caused by the mumps virus. Initial symptoms of mumps are non-specific and include fever, headache, malaise, muscle pain, and loss of appetite. These symptoms are usually followed by painful swelling of the parotid glands, called parotitis, which is the most common symptom of a mumps infection. Symptoms typically occur 16 to 18 days after exposure to the virus and resolve within two weeks. About one third of infections are asymptomatic.

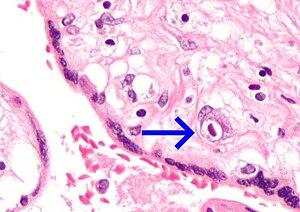

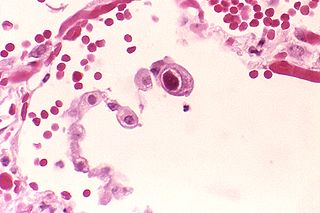

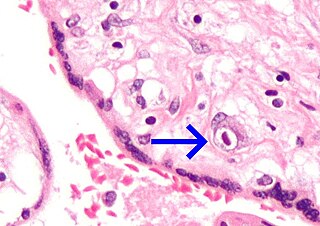

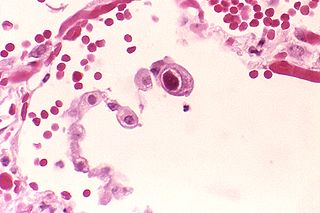

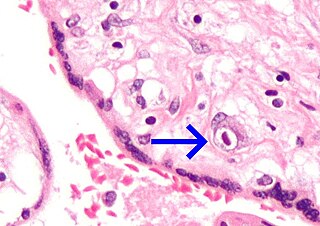

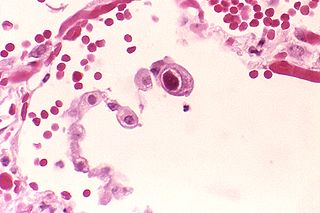

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a genus of viruses in the order Herpesvirales, in the family Herpesviridae, in the subfamily Betaherpesvirinae. Humans and other primates serve as natural hosts. The 11 species in this genus include human betaherpesvirus 5, which is the species that infects humans. Diseases associated with HHV-5 include mononucleosis and pneumonia, and congenital CMV in infants can lead to deafness and ambulatory problems.

Infectious mononucleosis, also known as glandular fever, is an infection usually caused by the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV). Most people are infected by the virus as children, when the disease produces few or no symptoms. In young adults, the disease often results in fever, sore throat, enlarged lymph nodes in the neck, and fatigue. Most people recover in two to four weeks; however, feeling tired may last for months. The liver or spleen may also become swollen, and in less than one percent of cases splenic rupture may occur.

Rubella, also known as German measles or three-day measles, is an infection caused by the rubella virus. This disease is often mild, with half of people not realizing that they are infected. A rash may start around two weeks after exposure and last for three days. It usually starts on the face and spreads to the rest of the body. The rash is sometimes itchy and is not as bright as that of measles. Swollen lymph nodes are common and may last a few weeks. A fever, sore throat, and fatigue may also occur. Joint pain is common in adults. Complications may include bleeding problems, testicular swelling, encephalitis, and inflammation of nerves. Infection during early pregnancy may result in a miscarriage or a child born with congenital rubella syndrome (CRS). Symptoms of CRS manifest as problems with the eyes such as cataracts, deafness, as well as affecting the heart and brain. Problems are rare after the 20th week of pregnancy.

Congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) occurs when an unborn baby is infected with the rubella virus via maternal-fetal transmission and develops birth defects. The most common congenital defects affect the ophthalmologic, cardiac, auditory, and neurologic systems.

Erythema infectiosum, fifth disease, or slapped cheek syndrome is one of several possible manifestations of infection by parvovirus B19. Fifth disease typically presents as a rash and is more common in children. While parvovirus B19 can affect humans of all ages, only two out of ten individuals will present with physical symptoms.

Congenital syphilis is syphilis that occurs when a mother with untreated syphilis passes the infection to her baby during pregnancy or at birth. It may present in the fetus, infant, or later. Clinical features vary and differ between early onset, that is presentation before age 2-years of age, and late onset, presentation after age 2-years. Infection in the unborn baby may present as poor growth, non-immune hydrops leading to premature birth or loss of the baby, or no signs. Affected newborns mostly initially have no clinical signs. They may be small and irritable. Characteristic features include a rash, fever, large liver and spleen, a runny and congested nose, and inflammation around bone or cartilage. There may be jaundice, large glands, pneumonia, meningitis, warty bumps on genitals, deafness or blindness. Untreated babies that survive the early phase may develop skeletal deformities including deformity of the nose, lower legs, forehead, collar bone, jaw, and cheek bone. There may be a perforated or high arched palate, and recurrent joint disease. Other late signs include linear perioral tears, intellectual disability, hydrocephalus, and juvenile general paresis. Seizures and cranial nerve palsies may first occur in both early and late phases. Eighth nerve palsy, interstitial keratitis and small notched teeth may appear individually or together; known as Hutchinson's triad.

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis (LCM) is a rodent-borne viral infectious disease that presents as aseptic meningitis, encephalitis or meningoencephalitis. Its causative agent is lymphocytic choriomeningitis mammarenavirus (LCMV), a member of the family Arenaviridae. The name was coined by Charles Armstrong in 1934.

Cytomegalovirus retinitis, also known as CMV retinitis, is an inflammation of the retina of the eye that can lead to blindness. Caused by human cytomegalovirus, it occurs predominantly in people whose immune system has been compromised, 15-40% of those with AIDS.

A vertically transmitted infection is an infection caused by pathogenic bacteria or viruses that use mother-to-child transmission, that is, transmission directly from the mother to an embryo, fetus, or baby during pregnancy or childbirth. It can occur when the mother has a pre-existing disease or becomes infected during pregnancy. Nutritional deficiencies may exacerbate the risks of perinatal infections. Vertical transmission is important for the mathematical modelling of infectious diseases, especially for diseases of animals with large litter sizes, as it causes a wave of new infectious individuals.

Betaherpesvirinae is a subfamily of viruses in the order Herpesvirales and in the family Herpesviridae. Mammals serve as natural hosts. There are 26 species in this subfamily, divided among 5 genera. Diseases associated with this subfamily include: human cytomegalovirus (HHV-5): congenital CMV infection; HHV-6: 'sixth disease' ; HHV-7: symptoms analogous to the 'sixth disease'.

Human betaherpesvirus 5, also called human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), is species of virus in the genus Cytomegalovirus, which in turn is a member of the viral family known as Herpesviridae or herpesviruses. It is also commonly called CMV. Within Herpesviridae, HCMV belongs to the Betaherpesvirinae subfamily, which also includes cytomegaloviruses from other mammals. CMV is a double-stranded DNA virus.

Zika fever, also known as Zika virus disease or simply Zika, is an infectious disease caused by the Zika virus. Most cases have no symptoms, but when present they are usually mild and can resemble dengue fever. Symptoms may include fever, red eyes, joint pain, headache, and a maculopapular rash. Symptoms generally last less than seven days. It has not caused any reported deaths during the initial infection. Mother-to-child transmission during pregnancy can cause microcephaly and other brain malformations in some babies. Infections in adults have been linked to Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS).

A Cytomegalovirus vaccine is a vaccine to prevent cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection or curb virus re-activation in persons already infected. Challenges in developing a vaccine include adeptness of CMV in evading the immune system and limited animal models. As of 2018 no such vaccine exists, although a number of vaccine candidates are under investigation. They include recombinant protein, live attenuated, DNA and other vaccines.

Blueberry muffin baby, also known as extramedullary hematopoiesis, describes a newborn baby with multiple purpura, associated with several non-cancerous and cancerous conditions in which extra blood is produced in the skin. The bumps range from one to seven mm, do not blanch and have a tendency to occur on the head, neck and trunk. They often fade by three to six weeks after birth, leaving brownish marks. When due to a cancer, the bumps tend to be fewer, firmer and larger.

Neonatal herpes simplex, or simply neonatal herpes, is a herpes infection in a newborn baby caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV), mostly as a result of vertical transmission of the HSV from an affected mother to her baby. Types include skin, eye, and mouth herpes (SEM), disseminated herpes (DIS), and central nervous system herpes (CNS). Depending on the type, symptoms vary from a fever to small blisters, irritability, low body temperature, lethargy, breathing difficulty, and a large abdomen due to ascites or large liver. There may be red streaming eyes or no symptoms.

Cytomegalovirus colitis, also known as CMV colitis, is an inflammation of the colon.

In sperm banks, screening of potential sperm donors typically includes screening for genetic diseases, chromosomal abnormalities and sexually transmitted infections (STDs) that may be transmitted through the donor's sperm. The screening process generally also includes a quarantine period, during which samples are frozen and stored for at least six months after which the donor will be re-tested for STIs. This is to ensure no new infections have been acquired or have developed during since the donation. If the result is negative, the sperm samples can be released from quarantine and used in treatments.

HIV in pregnancy is the presence of an HIV/AIDS infection in a woman while she is pregnant. There is a risk of HIV transmission from mother to child in three primary situations: pregnancy, childbirth, and while breastfeeding. This topic is important because the risk of viral transmission can be significantly reduced with appropriate medical intervention, and without treatment HIV/AIDS can cause significant illness and death in both the mother and child. This is exemplified by data from The Centers for Disease Control (CDC): In the United States and Puerto Rico between the years of 2014–2017, where prenatal care is generally accessible, there were 10,257 infants in the United States and Puerto Rico who were exposed to a maternal HIV infection in utero who did not become infected and 244 exposed infants who did become infected.

Neonatal infections are infections of the neonate (newborn) acquired during prenatal development or within the first four weeks of life. Neonatal infections may be contracted by mother to child transmission, in the birth canal during childbirth, or after birth. Neonatal infections may present soon after delivery, or take several weeks to show symptoms. Some neonatal infections such as HIV, hepatitis B, and malaria do not become apparent until much later. Signs and symptoms of infection may include respiratory distress, temperature instability, irritability, poor feeding, failure to thrive, persistent crying and skin rashes.