Measles is a highly contagious, vaccine-preventable infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than 40 °C (104 °F), cough, runny nose, and inflamed eyes. Small white spots known as Koplik's spots may form inside the mouth two or three days after the start of symptoms. A red, flat rash which usually starts on the face and then spreads to the rest of the body typically begins three to five days after the start of symptoms. Common complications include diarrhea, middle ear infection (7%), and pneumonia (6%). These occur in part due to measles-induced immunosuppression. Less commonly seizures, blindness, or inflammation of the brain may occur. Other names include morbilli, rubeola, red measles, and English measles. Both rubella, also known as German measles, and roseola are different diseases caused by unrelated viruses.

Rubella, also known as German measles or three-day measles, is an infection caused by the rubella virus. This disease is often mild, with half of people not realizing that they are infected. A rash may start around two weeks after exposure and last for three days. It usually starts on the face and spreads to the rest of the body. The rash is sometimes itchy and is not as bright as that of measles. Swollen lymph nodes are common and may last a few weeks. A fever, sore throat, and fatigue may also occur. Joint pain is common in adults. Complications may include bleeding problems, testicular swelling, encephalitis, and inflammation of nerves. Infection during early pregnancy may result in a miscarriage or a child born with congenital rubella syndrome (CRS). Symptoms of CRS manifest as problems with the eyes such as cataracts, deafness, as well as affecting the heart and brain. Problems are rare after the 20th week of pregnancy.

Teratology is the study of abnormalities of physiological development in organisms during their life span. It is a sub-discipline in medical genetics which focuses on the classification of congenital abnormalities in dysmorphology caused by teratogens. Teratogens are substances that may cause non-heritable birth defects via a toxic effect on an embryo or fetus. Defects include malformations, disruptions, deformations, and dysplasia that may cause stunted growth, delayed mental development, or other congenital disorders that lack structural malformations. The related term developmental toxicity includes all manifestations of abnormal development that are caused by environmental insult. The extent to which teratogens will impact an embryo is dependent on several factors, such as how long the embryo has been exposed, the stage of development the embryo was in when exposed, the genetic makeup of the embryo, and the transfer rate of the teratogen.

Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), formerly known as Steno-Fallot tetralogy, is a congenital heart defect characterized by four specific cardiac defects. Classically, the four defects are:

A birth defect, also known as a congenital disorder, is an abnormal condition that is present at birth regardless of its cause. Birth defects may result in disabilities that may be physical, intellectual, or developmental. The disabilities can range from mild to severe. Birth defects are divided into two main types: structural disorders in which problems are seen with the shape of a body part and functional disorders in which problems exist with how a body part works. Functional disorders include metabolic and degenerative disorders. Some birth defects include both structural and functional disorders.

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is a medical condition in which the ductus arteriosus fails to close after birth: this allows a portion of oxygenated blood from the left heart to flow back to the lungs through the aorta, which has a higher blood pressure, to the pulmonary artery, which has a lower blood pressure. Symptoms are uncommon at birth and shortly thereafter, but later in the first year of life there is often the onset of an increased work of breathing and failure to gain weight at a normal rate. With time, an uncorrected PDA usually leads to pulmonary hypertension followed by right-sided heart failure.

A congenital heart defect (CHD), also known as a congenital heart anomaly, congenital cardiovascular malformation, and congenital heart disease, is a defect in the structure of the heart or great vessels that is present at birth. A congenital heart defect is classed as a cardiovascular disease. Signs and symptoms depend on the specific type of defect. Symptoms can vary from none to life-threatening. When present, symptoms are variable and may include rapid breathing, bluish skin (cyanosis), poor weight gain, and feeling tired. CHD does not cause chest pain. Most congenital heart defects are not associated with other diseases. A complication of CHD is heart failure.

Neonatology is a subspecialty of pediatrics that consists of the medical care of newborn infants, especially the ill or premature newborn. It is a hospital-based specialty and is usually practised in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). The principal patients of neonatologists are newborn infants who are ill or require special medical care due to prematurity, low birth weight, intrauterine growth restriction, congenital malformations, sepsis, pulmonary hypoplasia, or birth asphyxia.

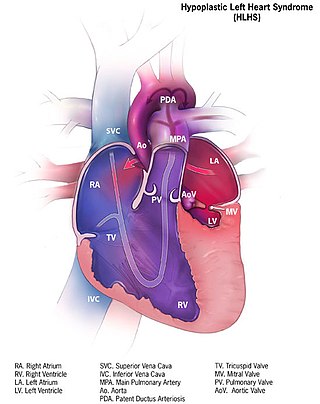

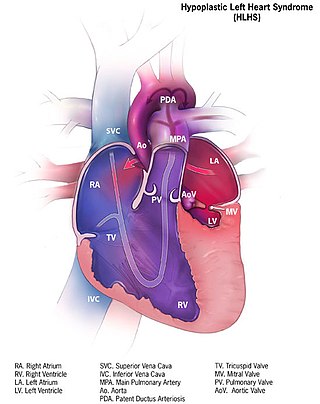

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) is a rare congenital heart defect in which the left side of the heart is severely underdeveloped and incapable of supporting the systemic circulation. It is estimated to account for 2-3% of all congenital heart disease. Early signs and symptoms include poor feeding, cyanosis, and diminished pulse in the extremities. The etiology is believed to be multifactorial resulting from a combination of genetic mutations and defects resulting in altered blood flow in the heart. Several structures can be affected including the left ventricle, aorta, aortic valve, or mitral valve all resulting in decreased systemic blood flow.

A vertically transmitted infection is an infection caused by pathogenic bacteria or viruses that use mother-to-child transmission, that is, transmission directly from the mother to an embryo, fetus, or baby during pregnancy or childbirth. It can occur when the mother has a pre-existing disease or becomes infected during pregnancy. Nutritional deficiencies may exacerbate the risks of perinatal infections. Vertical transmission is important for the mathematical modelling of infectious diseases, especially for diseases of animals with large litter sizes, as it causes a wave of new infectious individuals.

Interrupted aortic arch is a very rare heart defect in which the aorta is not completely developed. There is a gap between the ascending and descending thoracic aorta. In a sense it is the complete form of a coarctation of the aorta. Almost all patients also have other cardiac anomalies, including a ventricular septal defect (VSD), aorto-pulmonary window, and truncus arteriosus. There are three types of interrupted aortic arch, with type B being the most common. Interrupted aortic arch is often associated with DiGeorge syndrome.

Immunization during pregnancy is the administration of a vaccine to a pregnant individual. This may be done either to protect the individual from disease or to induce an antibody response, such that the antibodies cross the placenta and provide passive immunity to the infant after birth. In many countries, including the US, Canada, UK, Australia and New Zealand, vaccination against influenza, COVID-19 and whooping cough is routinely offered during pregnancy.

An attenuated vaccine is a vaccine created by reducing the virulence of a pathogen, but still keeping it viable. Attenuation takes an infectious agent and alters it so that it becomes harmless or less virulent. These vaccines contrast to those produced by "killing" the pathogen.

Zika fever, also known as Zika virus disease or simply Zika, is an infectious disease caused by the Zika virus. Most cases have no symptoms, but when present they are usually mild and can resemble dengue fever. Symptoms may include fever, red eyes, joint pain, headache, and a maculopapular rash. Symptoms generally last less than seven days. It has not caused any reported deaths during the initial infection. Mother-to-child transmission during pregnancy can cause microcephaly and other brain malformations in some babies. Infections in adults have been linked to Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS).

The central nervous system (CNS) controls most of the functions of the body and mind. It comprises the brain, spinal cord and the nerve fibers that branch off to all parts of the body. The CNS viral diseases are caused by viruses that attack the CNS. Existing and emerging viral CNS infections are major sources of human morbidity and mortality.

Rubella vaccine is a vaccine used to prevent rubella. Effectiveness begins about two weeks after a single dose and around 95% of people become immune. Countries with high rates of immunization no longer see cases of rubella or congenital rubella syndrome. When there is a low level of childhood immunization in a population it is possible for rates of congenital rubella to increase as more women make it to child-bearing age without either vaccination or exposure to the disease. Therefore, it is important for more than 80% of people to be vaccinated. By introducing rubella containing vaccines, rubella has been eradicated in 81 nations, as of mid-2020.

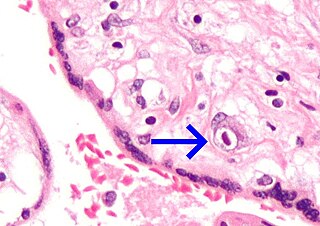

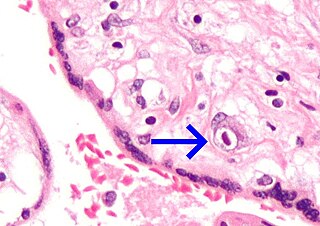

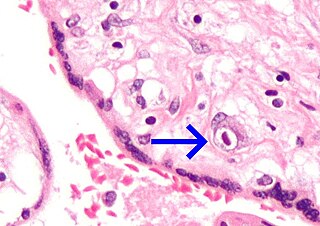

Blueberry muffin baby, also known as extramedullary hematopoiesis, describes a newborn baby with multiple purpura, associated with several non-cancerous and cancerous conditions in which extra blood is produced in the skin. The bumps range from one to seven mm, do not blanch and have a tendency to occur on the head, neck and trunk. They often fade by three to six weeks after birth, leaving brownish marks. When due to a cancer, the bumps tend to be fewer, firmer and larger.

Congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) is cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in a newborn baby. Most have no symptoms. Some affected babies are small. Other signs and symptoms include a rash, jaundice, hepatomegaly, retinitis, and seizures. It may lead to loss of hearing or vision, developmental disability, or a small head.

Neonatal infections are infections of the neonate (newborn) acquired during prenatal development or within the first four weeks of life. Neonatal infections may be contracted by mother to child transmission, in the birth canal during childbirth, or after birth. Neonatal infections may present soon after delivery, or take several weeks to show symptoms. Some neonatal infections such as HIV, hepatitis B, and malaria do not become apparent until much later. Signs and symptoms of infection may include respiratory distress, temperature instability, irritability, poor feeding, failure to thrive, persistent crying and skin rashes.

The 1962–1965 rubella epidemic was an outbreak of rubella across Europe and the United States.