Related Research Articles

Chloramphenicol is an antibiotic useful for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections. This includes use as an eye ointment to treat conjunctivitis. By mouth or by injection into a vein, it is used to treat meningitis, plague, cholera, and typhoid fever. Its use by mouth or by injection is only recommended when safer antibiotics cannot be used. Monitoring both blood levels of the medication and blood cell levels every two days is recommended during treatment.

Ciprofloxacin is a fluoroquinolone antibiotic used to treat a number of bacterial infections. This includes bone and joint infections, intra-abdominal infections, certain types of infectious diarrhea, respiratory tract infections, skin infections, typhoid fever, and urinary tract infections, among others. For some infections it is used in addition to other antibiotics. It can be taken by mouth, as eye drops, as ear drops, or intravenously.

Phenytoin (PHT), sold under the brand name Dilantin among others, is an anti-seizure medication. It is useful for the prevention of tonic-clonic seizures and focal seizures, but not absence seizures. The intravenous form, fosphenytoin, is used for status epilepticus that does not improve with benzodiazepines. It may also be used for certain heart arrhythmias or neuropathic pain. It can be taken intravenously or by mouth. The intravenous form generally begins working within 30 minutes and is effective for roughly 24 hours. Blood levels can be measured to determine the proper dose.

Clarithromycin, sold under the brand name Biaxin among others, is an antibiotic used to treat various bacterial infections. This includes strep throat, pneumonia, skin infections, H. pylori infection, and Lyme disease, among others. Clarithromycin can be taken by mouth as a pill or liquid.

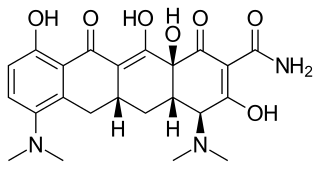

Minocycline, sold under the brand name Minocin among others, is a tetracycline antibiotic medication used to treat a number of bacterial infections such as pneumonia. It is generally less preferred than the tetracycline doxycycline. Minocycline is also used for the treatment of acne and rheumatoid arthritis. It is taken by mouth or applied to the skin.

Oxcarbazepine, sold under the brand name Trileptal among others, is a medication used to treat epilepsy. For epilepsy it is used for both focal seizures and generalized seizures. It has been used both alone and as add-on therapy in people with bipolar disorder who have had no success with other treatments. It is taken by mouth.

Clindamycin is an antibiotic medication used for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections, including osteomyelitis (bone) or joint infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, strep throat, pneumonia, acute otitis media, and endocarditis. It can also be used to treat acne, and some cases of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). In combination with quinine, it can be used to treat malaria. It is available by mouth, by injection into a vein, and as a cream or a gel to be applied to the skin or in the vagina.

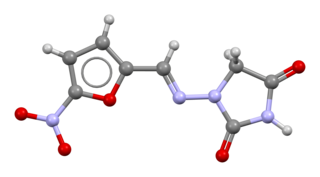

Nitrofurantoin is an antibacterial medication used to treat urinary tract infections, but it is not as effective for kidney infections. It is taken by mouth.

Pancytopenia is a medical condition in which there is significant reduction in the number of almost all blood cells.

Cefaclor, sold under the trade name Ceclor among others, is a second-generation cephalosporin antibiotic used to treat certain bacterial infections such as pneumonia and infections of the ear, lung, skin, throat, and urinary tract. It is also available from other manufacturers as a generic.

Norfloxacin, sold under the brand name Noroxin among others, is an antibiotic that belongs to the class of fluoroquinolone antibiotics. It is used to treat urinary tract infections, gynecological infections, inflammation of the prostate gland, gonorrhea and bladder infection. Eye drops were approved for use in children older than one year of age.

Amikacin is an antibiotic medication used for a number of bacterial infections. This includes joint infections, intra-abdominal infections, meningitis, pneumonia, sepsis, and urinary tract infections. It is also used for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. It is used by injection into a vein using an IV or into a muscle.

Flucytosine, also known as 5-fluorocytosine (5-FC), is an antifungal medication. It is specifically used, together with amphotericin B, for serious Candida infections and cryptococcosis. It may be used by itself or with other antifungals for chromomycosis. Flucytosine is used by mouth and by injection into a vein.

Women should speak to their doctor or healthcare professional before starting or stopping any medications while pregnant. Non-essential drugs and medications should be avoided while pregnant. Tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and illicit drug use while pregnant may be dangerous for the unborn baby and may lead to severe health problems and/or birth defects. Even small amounts of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana have not been proven to be safe when taken while pregnant. In some cases, for example, if the mother has epilepsy or diabetes, the risk of stopping a medication may be worse than risks associated with taking the medication while pregnant. The mother's healthcare professional will help make these decisions about the safest way to protect the health of both the mother and unborn child. In addition to medications and substances, some dietary supplements are important for a healthy pregnancy, however, others may cause harm to the unborn child.

Neonatal withdrawal or neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) or neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS) is a withdrawal syndrome of infants after birth caused by in utero exposure to drugs of dependence, most commonly opioids. Common signs and symptoms include tremors, irritability, vomiting, diarrhea, and fever. NAS is primarily diagnosed with a detailed medication history and scoring systems. First-line treatment should begin with non-medication interventions to support neonate growth, though medication interventions may be used in certain situations.

Sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine, sold under the brand name Fansidar, is a combination medication used to treat malaria. It contains sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine. For the treatment of malaria it is typically used along with other antimalarial medication such as artesunate. In areas of Africa with moderate to high rates of malaria, three doses are recommended during the second and third trimester of pregnancy.

Neonatal hypoglycemia occurs when the neonate's blood glucose level is less than the newborn's body requirements for factors such as cellular energy and metabolism. There is inconsistency internationally for diagnostic thresholds. In the US, hypoglycemia is when the blood glucose level is below 30 mg/dL within the first 24 hours of life and below 45 mg/dL thereafter. In the UK, however, lower and more variable thresholds are used. The neonate's gestational age, birth weight, metabolic needs, and wellness state of the newborn has a substantial impact on the neonates blood glucose level. There are known risk factors that can be both maternal and neonatal. This is a treatable condition. Its treatment depends on the cause of the hypoglycemia. Though it is treatable, it can be fatal if gone undetected. Hypoglycemia is the most common metabolic problem in newborns.

HIV in pregnancy is the presence of an HIV/AIDS infection in a woman while she is pregnant. There is a risk of HIV transmission from mother to child in three primary situations: pregnancy, childbirth, and while breastfeeding. This topic is important because the risk of viral transmission can be significantly reduced with appropriate medical intervention, and without treatment HIV/AIDS can cause significant illness and death in both the mother and child. This is exemplified by data from The Centers for Disease Control (CDC): In the United States and Puerto Rico between the years of 2014–2017, where prenatal care is generally accessible, there were 10,257 infants in the United States and Puerto Rico who were exposed to a maternal HIV infection in utero who did not become infected and 244 exposed infants who did become infected.

Neonatal infections are infections of the neonate (newborn) acquired during prenatal development or within the first four weeks of life. Neonatal infections may be contracted by mother to child transmission, in the birth canal during childbirth, or after birth. Neonatal infections may present soon after delivery, or take several weeks to show symptoms. Some neonatal infections such as HIV, hepatitis B, and malaria do not become apparent until much later. Signs and symptoms of infection may include respiratory distress, temperature instability, irritability, poor feeding, failure to thrive, persistent crying and skin rashes.

Meropenem/vaborbactam, sold under the brand name Vabomere among others, is a combination medication used to treat complicated urinary tract infections, complicated abdominal infections, and hospital-acquired pneumonia. It contains meropenem, a β-lactam antibiotic, and vaborbactam, a β-lactamase inhibitor. It is given by injection into a vein.

References

- ↑ McIntyre J, Choonara I (2004). "Drug toxicity in the neonate". Biology of the Neonate. 86 (4): 218–21. doi:10.1159/000079656. PMID 15249753. S2CID 29906856.

- 1 2 Deveci A, Coban AY (September 2014). "Optimum management of Citrobacter koseri infection". Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 12 (9): 1137–42. doi:10.1586/14787210.2014.944505. PMID 25088467. S2CID 37304019.

- 1 2 "Chloramphenicol", LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury, Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2012, PMID 31643435 , retrieved 2021-08-02

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Oong GC, Tadi P (2021). "Chloramphenicol". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32310426 . Retrieved 2021-08-02.

- ↑ Vázquez-Laslop N, Mankin AS (September 2018). "Context-Specific Action of Ribosomal Antibiotics". Annual Review of Microbiology. 72 (1): 185–207. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-090817-062329. PMC 8742604 . PMID 29906204.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Cummings ED, Kong EL, Edens MA (2021). "Gray Baby Syndrome". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 28846297 . Retrieved 2021-07-30.

- ↑ Powell DA, Nahata MC (April 1982). "Chloramphenicol: new perspectives on an old drug". Drug Intelligence & Clinical Pharmacy. 16 (4): 295–300. doi:10.1177/106002808201600404. PMID 7040026. S2CID 103247.

- ↑ Ingebrigtsen SG, Didriksen A, Johannessen M, Škalko-Basnet N, Holsæter AM (June 2017). "Old drug, new wrapping – A possible comeback for chloramphenicol?". International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 526 (1–2): 538–546. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.05.025. hdl: 10037/12466 . PMID 28506801.

- ↑ Beninger P (December 2018). "Pharmacovigilance: An Overview". Clinical Therapeutics. 40 (12): 1991–2004. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.07.012 . PMID 30126707.

- 1 2 Kasten MJ (1999). "Clindamycin, metronidazole, and chloramphenicol". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 74 (8): 825–33. doi:10.4065/74.8.825. PMID 10473362.

- ↑ Hammett-Stabler CA, Johns T (1998). "Laboratory guidelines for monitoring of antimicrobial drugs". Clinical Chemistry. 44 (5): 1129–40. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/44.5.1129 . PMID 9590397.

- ↑ Chambers HF (2005). "Chapter 46. Protein Synthesis Inhibitors and Miscellaneous Antibacterial Agents". In Brunton EL, Lazo JS, Parker K (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1173–1202. ISBN 978-0-07-142280-2.

- ↑ Meissner HC, Smith AL (1979). "The current status of chloramphenicol". Pediatrics. 64 (3): 348–56. doi:10.1542/peds.64.3.348. PMID 384354. S2CID 33410918.

- ↑ "Chloramphenicol". Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2006. PMID 30000554 . Retrieved 2021-07-30.

- 1 2 3 "Chloramphenicol". WHO model formulary for children 2010. World Health Organization. 2010. pp. 99–101. hdl:10665/44309. ISBN 978-92-4-159932-0.

- ↑ Yu PA, Tran EL, Parker CM, Kim HJ, Yee EL, Smith PW, et al. (2020). "Safety of Antimicrobials During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review of Antimicrobials Considered for Treatment and Postexposure Prophylaxis of Plague". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 70 (Suppl 1): S37–S50. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1231 . PMID 32435799.

- ↑ Feder HM (1986). "Chloramphenicol: what we have learned in the last decade". Southern Medical Journal. 79 (9): 1129–34. doi:10.1097/00007611-198609000-00022. PMID 3529436.

- 1 2 Mulhall A, de Louvois J, Hurley R (1983). "Chloramphenicol toxicity in neonates: its incidence and prevention". British Medical Journal. 287 (6403): 1424–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.287.6403.1424. PMC 1549666 . PMID 6416440.

- ↑ Forster J, Hufschmidt C, Niederhoff H, Künzer W (1985). "[Need for the determination of chloramphenicol levels in the treatment of bacterial-purulent meningitis with chloramphenicol succinate in infants and small children]". Monatsschrift Kinderheilkunde. 133 (4): 209–13. PMID 4000136.

- ↑ Meyers RS, Thackray J, Matson KL, McPherson C, Lubsch L, Hellinga RC, Hoff DS (2020). "Key Potentially Inappropriate Drugs in Pediatrics: The KIDs List". The Journal of Pediatric Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 25 (3): 175–191. doi:10.5863/1551-6776-25.3.175. PMC 7134587 . PMID 32265601.

- ↑ Aggarwal R, Sarkar N, Deorari AK, Paul VK (2001). "Sepsis in the newborn". Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 68 (12): 1143–7. doi:10.1007/BF02722932. PMID 11838570. S2CID 20554642.

- ↑ Grijalva J, Vakili K (2013). "Neonatal liver physiology". Seminars in Pediatric Surgery. 22 (4): 185–9. doi:10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2013.10.006. PMID 24331092.

- ↑ Werth, Brian J (2020). "Chloramphenicol". MSD Manual Professional Edition. Retrieved 2021-07-30.

- ↑ Padberg S (2016). "Chloramphenicol". In Schaefer C, Peters P, Miller RK (eds.). Meyler's Side Effects of Drugs: The International Encyclopedia of Adverse Drug Reactions and Interactions (Sixteenth ed.). Amsterdam. pp. 229–236. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53717-1.00472-8. ISBN 978-0-444-53716-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Padberg S (2015). "Anti-infectives". Drugs During Pregnancy and Lactation (Third ed.). Academic Press. pp. 687–703. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-408078-2.00029-9. ISBN 9780124080782.

- ↑ National Toxicology Program (2011). "NTP 12th Report on Carcinogens". Report on Carcinogens: Carcinogen Profiles. 12: iii–499. ISSN 1551-8280. PMID 21822324.

- 1 2 Shalkham AS, Kirrane BM, Hoffman RS, Goldfarb DS, Nelson LS (2006). "The availability and use of charcoal hemoperfusion in the treatment of poisoned patients". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 48 (2): 239–41. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.04.080 . PMID 16860189.