Related Research Articles

Adjudication is the legal process by which an arbiter or judge reviews evidence and argumentation, including legal reasoning set forth by opposing parties or litigants, to come to a decision which determines rights and obligations between the parties involved.

The High Court of Australia is Australia's apex court. It exercises original and appellate jurisdiction on matters specified within Australia's Constitution.

Tort law in Australia is substantively similar to that of other common law jurisdictions, especially at a foundational level. This is due to the legal system of Australia having been derived from the UK, like most other common law nations around the globe.

A court of equity, equity court or chancery court is a court that is authorized to apply principles of equity, as opposed to those of law, to cases brought before it.

The judiciary of Australia comprises judges who sit in federal courts and courts of the States and Territories of Australia. The High Court of Australia sits at the apex of the Australian court hierarchy as the ultimate court of appeal on matters of both federal and State law.

The District Court of Western Australia is the intermediate court in Western Australia. The District Court commenced in 1970, amid additional stress placed on the existing Magistrates Court and Supreme Court due to the increasing population of Western Australia. At its inception, the Court consisted of four judges: Sydney Howard Good, William Page Pidgeon, Desmond Charles Heenan and Robert Edmond Jones.

The criminal law of Australia is the body of law in Australia that relates to crime.

In Greece, the Special Highest Court, is provided for in the article 100 of the Constitution of Greece. It is not a permanent court and it sits only when a case belonging to its special competence arises. It is regarded as the supreme "constitutional" and "electoral" court of Greece. Its decisions are irrevocable and binding for all the courts, including the Supreme Courts. However, the Special Highest Court does not have an hierarchical relation with the three Supreme Courts. It is not considered higher than these courts and it does not belong to any branch of the Greek justice system.

Sue v Hill was an Australian court case decided in the High Court of Australia on 23 June 1999. It concerned a dispute over the apparent return of a candidate, Heather Hill, to the Australian Senate in the 1998 federal election. The result was challenged on the basis that Hill was a dual citizen of the United Kingdom and Australia, and that section 44(i) of the Constitution of Australia prevents any person who is the citizen of a "foreign power" from being elected to the Parliament of Australia. The High Court found that, at least for the purposes of section 44(i), the United Kingdom is a foreign power to Australia.

The Court of Disputed Returns in New South Wales is a court within the Australian court hierarchy established initially in 1928 pursuant to the Parliamentary Electorates and Elections Amendment Act, and since 2017 pursuant to the Electoral Act 2017. The jurisdiction of the Court is exercised by the Supreme Court of New South Wales and the Court considers petitions concerning the validity of any election or return under the Act. The Court is concerned with elections held for the New South Wales Parliament and local government elections within the state.

The Industrial Relations Commission of New South Wales conciliates and arbitrates industrial disputes, sets conditions of employment and fixes wages and salaries by making industrial awards, approves enterprise agreements and decides claims of unfair dismissal in New South Wales, a state of Australia. The Commission was established with effect from 2 September 1996 pursuant to the Industrial Relations Act 1996.

The Court of Disputed Returns in Australia is a special jurisdiction of the High Court of Australia. The High Court, sitting as the Court of Disputed Returns, hears challenges regarding the validity of federal elections. The jurisdiction is twofold: (1) on a petition to the Court by an individual with a relevant interest or by the Australian Electoral Commission, or (2) on a reference by either house of the Commonwealth Parliament. This jurisdiction was initially established by Part XVI of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1902 and is now contained in Part XXII of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918. Challenges regarding the validity of State elections are heard by the Supreme Court of that State as the State's Court of Disputed Returns.

The Queensland Court of Disputed Returns is a court that adjudicates disputes concerning Queensland Government and local government elections and state referendums in Queensland, Australia. The Court is a division of the Supreme Court of Queensland.

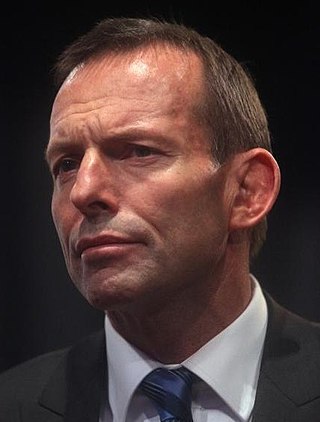

The 2013 Australian federal election to elect the members of the 44th Parliament of Australia took place on 7 September 2013. The centre-right Liberal/National Coalition opposition led by Opposition leader Tony Abbott of the Liberal Party of Australia and Coalition partner the National Party of Australia, led by Warren Truss, defeated the incumbent centre-left Labor Party government of Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in a landslide. Labor had been in government for six years since being elected in the 2007 election. This election marked the end of the Rudd-Gillard-Rudd Labor government and the start of the 9 year long Abbott-Turnbull-Morrison Liberal-National Coalition government. Abbott was sworn in by the Governor-General, Quentin Bryce, as Australia's new Prime Minister on 18 September 2013, along with the Abbott Ministry. The 44th Parliament of Australia opened on 12 November 2013, with the members of the House of Representatives and territory senators sworn in. The state senators were sworn in by the next Governor-General Peter Cosgrove on 7 July 2014, with their six-year terms commencing on 1 July.

The Supreme Court of Kenya is the highest court in Kenya. It is established under Article 163 of the Kenyan Constitution. As the highest court in the nation, its decisions are binding and set precedent on all other courts in the country.

Blundell v Vardon, was the first of three decisions of the High Court of Australia concerning the 1906 election for senators for South Australia. Sitting as the Court of Disputed Returns, Barton J held that the election of Anti-Socialist Party candidate Joseph Vardon as the third senator for South Australia was void due to irregularities in the way the returning officers marked some votes. The Parliament of South Australia appointed James O'Loghlin. Vardon sought to have the High Court compel the governor of South Australia to hold a supplementary election, however the High Court held in R v Governor of South Australia; Ex parte Vardon that it had no power to do so. Vardon then petitioned the Senate seeking to remove O'Loghlin and rather than decide the issue, the Senate referred the matter to the High Court. The High Court held in Vardon v O'Loghlin that O'Loghlin had been invalidly appointed and ordered a supplementary election. Vardon and O'Loghlin both contested the supplementary election, with Vardon winning with 54% of the vote.

Chanter v Blackwood and the related case of Maloney v McEacharn were a series of decisions of the High Court of Australia, sitting as the Court of Disputed Returns arising from the 1903 federal election for the seats of Riverina and Melbourne in the House of Representatives. Chanter v Blackwood , and Maloney v McEacharn , determined questions of law as to the validity of certain votes. In Chanter v Blackwood Griffith CJ held that 91 votes were invalid and because this exceeded the majority, the election was void, while Chanter v Blackwood dealt with questions of costs. In Maloney v McEacharn more than 300 votes were found to be invalid and the parties agreed it was appropriate for the election to be declared void.

Alley v Gillespie, was a significant decision of the High Court of Australia that considered the purpose and scope of s 46 of the Australian Constitution. It was the first application brought under the Common Informers Act 1975 (Cth).

The Electoral Count Act of 1887 (ECA) (Pub. L. 49–90, 24 Stat. 373, later codified at Title 3, Chapter 1) is a United States federal law adding to procedures set out in the Constitution of the United States for the counting of electoral votes following a presidential election. The Act was enacted by Congress in 1887, ten years after the disputed 1876 presidential election, in which several states submitted competing slates of electors and a divided Congress was unable to resolve the deadlock for weeks. Close elections in 1880 and 1884 followed, and again raised the possibility that with no formally established counting procedure in place, partisans in Congress might use the counting process to force a desired result.

A by-election was held for the New South Wales Legislative Assembly electorate of Gordon on 24 September 1938 because the Court of Disputed Returns overturned the result of the 1938 Gordon election. Harry Turner had been declared elected by 9 votes over William Milne. Both candidates were endorsed by the United Australia Party. Milne filed a petition which challenged postal and absentee votes. Justice Maxwell sitting as the Court of Disputed Returns held that most of the 125 challenged votes did not meet the requirement of the Electoral Act such as not being properly witnessed, and that the election was void.

References

- ↑ Orr & Williams, 55.

- 1 2 Orr & Williams, 56.

- 1 2 Orr & Williams, 57.

- ↑ Orr & Williams, 58.

- ↑ 10 Geo 3 ch 16

- ↑ Orr & Williams, 60.

- ↑ Strickland v Grima (Malta) [1930] UKPC 7 , (1930) AC 285

- ↑ Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) s 354 The Court of Disputed Returns.

- ↑ Electoral Act 1992 (ACT) s 252 Court of Disputed Elections.

- ↑ Parliamentary Electorates and Elections Act 1912 (NSW) s 156 The Court of Disputed Returns.

- ↑ Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW) s 124 Councillors pending determination of disputed return.

- ↑ Electoral Act (NT) s 234 Constitution.

- ↑ Electoral Act 1992 (Qld) s 137 Supreme Court to be Court of Disputed Returns.

- ↑ Electoral Act 1985 (SA) s 103 The Court of Disputed Returns.

- ↑ Local Government (Elections) Act 1999 (SA) s 67 Constitution of the Court.

- ↑ Electoral Act 2002 (Vic) s 124 The Court of Disputed Returns.

- ↑ Electoral Act 1907 (WA) s 157 Validity of election or return, how to dispute.

- ↑ Local Government Act 1995 (WA) s 4.81 Complaints to go to Court of Disputed Returns.

- ↑ Geiringer, 144.

- ↑ "Organic Law on National and Local-level Government Elections". Paclii.org. 21 September 2006. Retrieved 4 June 2010.