Sagitta is a dim but distinctive constellation in the northern sky. Its name is Latin for 'arrow', not to be confused with the significantly larger constellation Sagittarius 'the archer'. It was included among the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy, and it remains one of the 88 modern constellations defined by the International Astronomical Union. Although it dates to antiquity, Sagitta has no star brighter than 3rd magnitude and has the third-smallest area of any constellation.

Lambda1 Tucanae is the Bayer designation for one member of a pair of stars sharing a common proper motion through space, which lie within the southern constellation of Tucana. As of 2013, the pair had an angular separation of 20.0 arc seconds along a position angle of 82°. Together, they are barely visible to the naked eye with a combined apparent visual magnitude of 6.21. Based upon an annual parallax shift for both stars of approximately 16.5 mas as seen from Earth, this system is located roughly 198 light years from the Sun.

V337 Carinae is a K-type bright giant star in the constellation of Carina. It is an irregular variable and has an apparent visual magnitude which varies between 3.36 and 3.44.

D Centauri is a double star in the southern constellation of Centaurus. The system is faintly visible to the naked eye as a point of light with a combined apparent magnitude of +5.31; the two components are of magnitude 5.78 and 6.98, respectively. It is located at a distance of approximately 610 light years from the Sun based on parallax, and is drifting further away with a radial velocity of ~10 km/s.

Delta Crateris is a solitary star in the southern constellation of Crater. With an apparent visual magnitude of 3.56, it is the brightest star in this rather dim constellation. It has an annual parallax shift of 17.56 mas as measured from Earth, indicating Delta Crateris lies at a distance of 163 ± 4 light years from the Sun.

HD 224635 and HD 224636 is a pair of stars comprising a binary star system in the constellation Andromeda. They are located approximately 94 light years away and they orbit each other every 717 years.

HD 7853 is a double star in the constellation Andromeda. With an apparent magnitude of 6.46, it can barely be seen with the naked eye even on the best of nights. The system is located approximately 130 parsecs (420 ly) distant, and the brighter star is an Am star, meaning that it has unusual metallic absorption lines. The spectral classification of kA5hF1mF2 means that it would have a spectral class of A5 if it were based solely on the calcium K line, F2 if based on the lines of other metals, and F1 if based on the hydrogen absorption lines. The two components are six arc-seconds apart and the secondary is three magnitudes fainter than the primary.

R Arae is an Algol-type eclipsing binary in the constellation Ara. Located approximately 298 parsecs (970 ly) distant, it normally shines at magnitude 6.17, but during eclipses can fall as low as magnitude 7.32. It has been suggested by multiple studies that mass transfer is occurring between the two stars of this system, and the period of eclipses seems to be increasing over time. The primary is a blue-white main sequence star of spectral type B5V that is 5 times as massive as the Sun, while the secondary is a yellow-white star of spectral type F1IV that is 1.5 times as massive as the Sun. Stellar material is being stripped off the secondary and accreting on the primary.

Zeta1 Antliae is the Bayer designation for a binary star system in the southern constellation of Antlia. Based upon parallax measurements, the pair are located at a distance of roughly 350 light-years from Earth. They have apparent magnitudes of +6.20 and +7.01 and are separated by 8.042 arcseconds. The apparent magnitude of the combined system is +5.76, which is bright enough to be seen with the naked eye in suitably dark skies.

ADS 48 is a multiple star system in the constellation of Andromeda consisting of 7 stars. The components, in order from A to G, have apparent visual magnitudes of 8.826, 8.995, 13.30, 12.53, 11.68, 9.949, and 13.00.

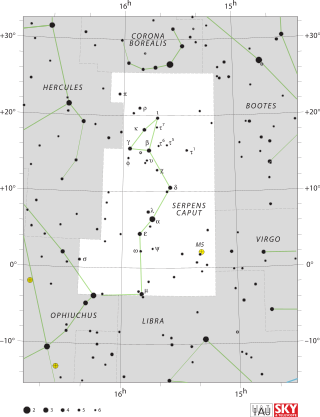

1 Serpentis is a red giant in the constellation Virgo with an apparent magnitude of 5.5. It is a red clump giant, a cool horizontal branch star that is fusing helium in its core. It has expanded to over 13 times the radius of the Sun and although it is cooler at 4,581 K it is 77 times more luminous. It is 322 light years away.

29 Camelopardalis is a double star in the circumpolar constellation Camelopardalis. With an apparent magnitude of 6.59, it's right below the max visibility to the naked eye, and can only be viewed under phenomenal conditions. The star is located 484 light years away based on parallax, but is drifting further away with a radial velocity of 3.9 km/s.

HD 102350 is a single star in the constellation Centaurus. It has a yellow hue and is visible to the naked eye with an apparent visual magnitude of 4.11. The distance to this star is approximately 390 light years based on parallax, but it is drifting closer with a radial velocity of −3 km/s. It has an absolute magnitude of −1.51.

Zeta Crateris is a binary star system in the southern constellation of Crater. Zeta Crateris appears to be about half-way between Epsilon Corvi to the southeast and Delta Crateris to the northwest, and marks the lower left corner of the rim of the bowl. Eta Crateris lies somewhat less than half of the way from Zeta Crateris to Gamma Corvi, the bright star above, (north) of Epsilon Corvi.

Epsilon Crateris is a solitary star in the southern constellation of Crater. Visible to the naked eye, it has an apparent visual magnitude of 4.84. It is located in the sky above Beta Crateris, and slightly to the left, or east, marking the lower right edge of the rim of the bowl and is somewhat closer to Theta Crateris, which is further east at the top of the bowl. With an annual parallax shift of 8.67 mas as seen from the Earth, its estimated distance is around 376 light years from the Sun.

Theta Sagittae (θ Sagittae) is a double star in the northern constellation of Sagitta. With a combined apparent visual magnitude of +6, it is near the limit of stars that can be seen with the naked eye. According to the Bortle scale the star is visible in dark suburban/rural skies. Based upon an annual parallax shift of 22.15 mas as seen from Earth, it is located roughly 147 light years from the Sun.

Chi1 Hydrae is a binary star in the equatorial constellation of Hydra. It originally received the Flamsteed designation of 9 Crateris before being placed in the Hydra constellation. Based upon an annual parallax shift of 22.8 mas as seen from Earth, it is located about 143 light years from the Sun. It is visible to the naked eye with a combined apparent visual magnitude of 4.94.

Tau1 Hydrae is a triple star system in the equatorial constellation of Hydra. Based upon the annual parallax shift of the two visible components as seen from Earth, they are located about 18 parsecs (59 ly) from the Sun. The system has a combined apparent visual magnitude of +4.59, which is bright enough to be visible to the naked eye at night.

3 Monocerotis is a binary star system in the equatorial constellation of Monoceros, located approximately 780 light years away from the Sun based on parallax. It is visible to the naked eye as a faint, blue-white hued star with a combined apparent visual magnitude of 4.92. The system is moving further from the Earth with a heliocentric radial velocity of +39 km/s.

53 Ophiuchi is a multiple star system in the equatorial constellation of Ophiuchus. It is visible to the naked eye as a faint star with a combined apparent visual magnitude of 5.80. Located around 370 light years distant from the Sun based on parallax, it is moving closer to the Earth with a heliocentric radial velocity of −14 km/s. As of 2011, the visible components had an angular separation of 41.28″ along a position angle of 190°. The primary may itself be a close binary system with a separation of 0.3692″ and a magnitude difference of 3.97 at an infrared wavelength of 562 nm.