Police corruption is a form of police misconduct in which law enforcement officers end up breaking their political contract and abusing their power for personal gain. This type of corruption may involve one or a group of officers. Internal police corruption is a challenge to public trust, cohesion of departmental policies, human rights and legal violations involving serious consequences. Police corruption can take many forms, such as bribery.

The obshchak (Russian), obštšak, or ühiskassa (Estonian) or "common treasury" is a traditional umbrella organisation of criminal groups in Estonia, a trade union of sorts that settles conflicts and establishes boundaries of the spheres of interest of various groups such as the Estonian mafia and Russian mafia. Between 2003 and 2016, the Common Fund was dominated by Nikolai Tarankov (1953–2016) of Russian heritage and KGB training. However, Tarankov was found murdered in Haapsalu, apparently in a revenge murder related to his past actions. The Common Fund pays for lawyers of caught members, purchases and delivers packages to imprisoned members, and covers other expenses. The organization has about ten member groups. The members have also operated significantly in Finland, where in 2009, high-level drug dealing was controlled by Estonians.

Crime in Russia refers to the multivalent issues of organized crime, extensive political and police corruption, and all aspects of criminality at play in Russia. Violent crime in Siberia is much more apparent than in Western Russia.

The Finnish Anti-Fascist Committee, also known by its Finnish abbreviation SAFKA, is a radical political organisation operating in Finland, founded in November 2008, but never registered. According to the Chairperson Johan Bäckman the committee has twenty activists and about a hundred supporters.

Erkki Johan Bäckman is a Finnish political activist, propagandist, author, eurosceptic, and convicted stalker working for the Russian government. Bäckman has been a prominent Finnish propagandist in Russia who has actively participated in long-standing operations to propagate anti-Finnish and anti-Western Russian propaganda.

The Philippines suffers from widespread corruption, which developed during the Spanish colonial period. According to GAN Integrity's Philippines Corruption Report updated May 2020, the Philippines suffers from many incidents of corruption and crime in many aspects of civic life and in various sectors. Such corruption risks are rampant throughout the state's judicial system, police service, public services, land administration, and natural resources. Examples of corruption in the Philippines include graft, bribery, favouritism, nepotism, impunity, embezzlement, extortion, racketeering, fraud, tax evasion, lack of transparency, lack of sufficient enforcement of laws and government policies, and consistent lack of support for human rights.

Slovakia is a Central European country with a history of relatively low crime. While crime became more widespread after the Revolutions of 1989, it remains low when compared to many other post-communist countries.

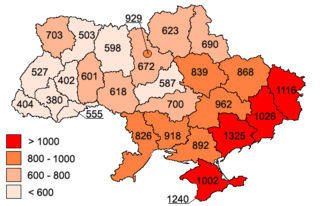

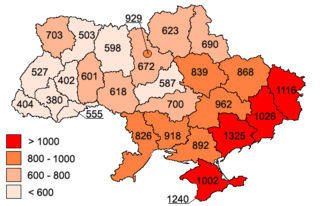

The fight against crime in Ukraine is led by the Ukrainian Police and certain other agencies. Due to the hard economic situation in the 1990s, the crime rate rose steadily to a peak in 2000. Following this peak, the crime rate declined, until 2009. In that year, the world financial crisis reached Ukraine.

Crime in Bulgaria is combated by the Bulgarian police and other agencies. The UK Government ranks Bulgaria as a low crime area and crime there has significantly decreased in recent years.

Crime in Denmark is combated by the Danish Police and other agencies.

Crime in Hungary is combated by the Hungarian police and other agencies.

Finland's overall corruption is relatively low, according to public opinion and global indexes and standards. The 2022 Corruption Perceptions Index released by Transparency International scored Finland at 87 on a scale from 0 to 100. When ranked by score, Finland shared second place with New Zealand among the 180 countries in the Index, where the country or countries ranked first are perceived to have the most honest public sector. For comparison, the best score was 90, the worst score was 12 and the average was 43.

Corruption in Mexico has permeated several segments of society – political, economic, and social – and has greatly affected the country's legitimacy, transparency, accountability, and effectiveness. Many of these dimensions have evolved as a product of Mexico's legacy of elite, oligarchic consolidation of power and authoritarian rule.

Examples of areas where Cambodians encounter corrupt practices in their everyday lives include obtaining medical services, dealing with alleged traffic violations, and pursuing fair court verdicts. Companies are urged to be aware when dealing with extensive red tape when obtaining licenses and permits, especially construction related permits, and that the demand for and supply of bribes are commonplace in this process. The 2010 Anti-Corruption Law provides no protection to whistleblowers, and whistleblowers can be jailed for up to 6 months if they report corruption that cannot be proven.

Corruption in Slovakia is a serious and ongoing problem.

Corruption in Bolivia is a major problem that has been called an accepted part of life in the country. It can be found at all levels of Bolivian society. Citizens of the country perceive the judiciary, police and public administration generally as the country's most corrupt. Corruption is also widespread among officials who are supposed to control the illegal drug trade and among those working in and with extractive industries.

Corruption in Guinea-Bissau occurs at among the highest levels in the world. In Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index for 2022, Guinea-Bissau scored 21 on a scale from 0 to 100. When ranked by score, Guinea-Bissau ranked 164th among the 180 countries in the Index, where the country ranked 180th is perceived to have the most corrupt public sector. For comparison, the best score in 2022 was 90, and the worst score was 12. Guinea-Bissau's score has either improved or remained steady every year since its low point in 2018, when it scored 16. In 2013, Guinea-Bissau scored below the averages for both Africa and West Africa on the Mo Ibrahim Foundation’s Index of African Governance.

Transparency International defines corruption as "the abuse of entrusted power for private gain". Transparency International's 2022 Corruption Perceptions Index scored the United Kingdom at 73 on a scale from 0 to 100. When ranked by score, the United Kingdom ranked 18th among the 180 countries in the Index, where the country ranked first is perceived to have the most honest public sector. For comparison with worldwide scores, the best score was 90, the worst score was 12, and the average score was 43. For comparison with regional scores, the highest score among Western European and European Union countries was 90, the average score was 66 and the lowest score was 42. The United Kingdom's score of 73 in 2022 was its lowest ever in the eleven years that the current version of the Index has been published.

Crime in Latvia is usually low, especially compared to previous years, when it was named the "crime capital of Europe" by Forbes in 2008. The homicide rate in Latvia was 3.9 cases per 100,000 people in 2019, a sharp drop from 10 cases per 100,000 people in 2000, and has been steadily decreasing, but has seen recent increases. The United States Department of State has assessed Latvia's security rating as "medium", with a moderate crime rate. In recent times, crime has been increasing, particularly due to many Latvians stranded because of the COVID-19 pandemic returning to Latvia and choosing to commit crime. According to Interpol, Latvia is considered an attractive place for regional and organized criminals involved in drug trafficking, arms trafficking, human trafficking, or smuggling. According to the Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia, a third of all women in Latvia have suffered some form of sexual violence or rape while men are subjected to violence outside the family.